December 27-2013

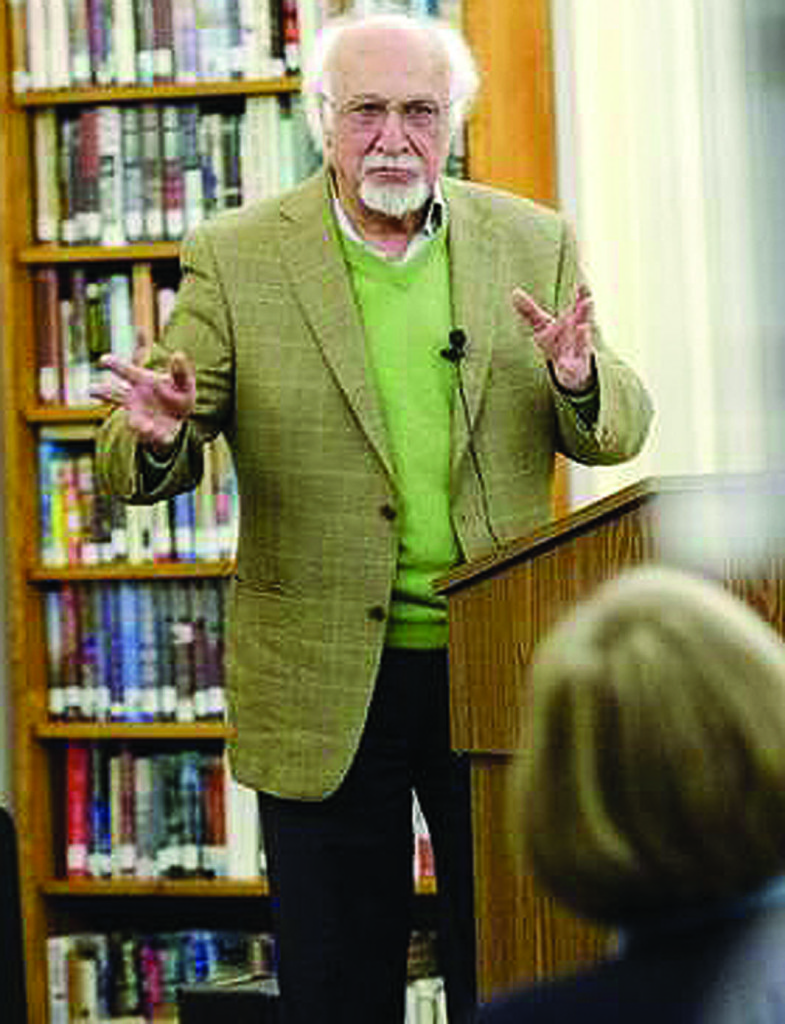

Mansour Farhang, who was the Islamic Republic’s first ambassador to the UN but soon split with the regime over its support for hostage taking, says the Islamic Republic and the Muslim Brotherhood are just bumps in the road of social development and will soon pass into history.

Rule by a popular, tyrannical majority — even an elected majority — is a messy but necessary step toward a more pluralistic, human-rights oriented democracy, he told a rapt audience of Americans during a lecture in the library of the small Vermont community of Essex Junction.

More tolerant societies will emerge from sectarian infighting, he declared; “God-given democracy” espoused by Islamists, will wither.

But when asked how long that would take, he ducked, saying only “eventually.”

Farhang has lived in Vermont for 30 years, teaching at Bennington College since he ran into the buzz saw of the Islamic Republic.

The Burlington Free Press reported on his lecture and said Farhang traced his optimism to both personal experience and his reading of centuries of European and Middle Eastern history.

As a high school student in Tehran, Farhang joined Amnesty International. As a college student in the US in the 1960s, he studied politics.

While serving as the first UN ambassador from revolutionary Iran, he resigned in protest over the theocracy’s holding of American hostages and drew the wrath of the regime. The FBI informed him he was on a regime’s hit list of hated dissidents.

Farhang lectured not just on the Iranian experience but also on the Arab world’s turmoil. Each part of the region, he said, has contorted uniquely since World War I, through passages of tribal rule, colonial servitude, nationalism and religious identity.

After the fall of the Ottoman Empire, many countries like Lebanon, Syria and Iraq were born as French and English colonies, created “by people who paid very little attention to the ethnic and religious fragmentation of the region.

“After gaining independence, they were ruled fundamentally by dictators, the dominant elites who had cooperated with colonial powers. The result was a militarization of politics.”

On the other hand, Iran and Egypt “both have ancient legacies of national identity. And perhaps as a result, neither is bound by tribalism. In fact, tribalism throughout the Middle East has diminished a great deal in the past 10, 20 years. And it’s important to remember that most of the European countries were tribal at one time.”

As for Islam, “There are powerful factions who see it as a cultural system, not simply as a religion. They wish to transform the face of a religion into a utopian ideology that promises to solve all of society’s problems.

“It’s similar to Christian fundamentalists in the US. Islamists emphasize family values, social conservatism and attracting followers from different social classes. It is a value system with a wide reach and one that offers comfort and solace to millions who feel caught up between tradition and modernity.”

“Theirs is a clash within a culture, within Islam. You have literalists interpreting scriptures, and you have more metaphorical, or historical interpretations.

“It’s not really all that different from what happened in the West, if we go back to the Enlightenment [in the 1700s] and study how cultural change is the slowest kind of change we see in society.

“From that beginning, it took the Western world a century and a half to transform itself with the suffragist movement, the abolitionist and civil rights movements and, at the present time, the sexual equality, gender equality movements.”

Democracy, he said, “is very appealing and very interesting”—as an abstraction. “But the moment it begins to recognize the plurality of values and perspectives, including religious minorities, the response becomes schizophrenic.

“When people with Western influences talk about democracy, they mean constitutional democracy, human-rights-based democracy.

“In Islamist nations, when the leaders talk about democracy, they’re talking about a ‘majoritarian’ democracy. In other words, the majority comes to power and decides what is in the best interest of society, and they impose it.

“They’re talking about ‘one person, one vote, one time.’

“In other words, the majority can become tyrannical, and still feel justified because they represent the majority of the people. And that conflict is irresolvable.”

Farhang said, “The demonstrations of 2010 and 2011 in Egypt, Tunisia and in Syria were initially organized mostly by urban-based young people and women — modernists, secularists. They followed no charismatic leaders, which is unusual in the region.

“Yet when the dictators were ousted and elections took place, Islamists were the winners. The secularists could not take power because they were fragmented and had little contact with the urban and rural poor — largely because of a deep social cultural gap between them.

“Under those dictatorships, the clergy had been prevented from participation in politics, but the mosques stayed open. I mean, you can’t close the mosques!

“So groups like the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, who were banned as a political party, established clinics, schools and charities.

“They developed a far greater understanding of the feelings and sensibilities of the poor. And the poor are much more susceptible to an ideology — this religion—that connects with their sensibilities, rather than the liberal or leftist or social democratic people who are presenting ideas largely borrowed from the West.”

“When you’re intensely committed to something, whether it’s leftist or rightist, the intensity of preference leads to a kind of unity, a solidarity. For liberals and progressive secularists—the kind I have personally identified with all my life—we’re far more fragmented and divided, in large part because of our commitment to pluralism, respect for individual preference.”

Farhang said, “In Islam, if you’re interested in economic equality, the Qoran will give you all kinds of verses. It’s the same with ethnicity, tribalism, with respect for elders. But when it comes to women, or religious minorities, the equality stops.

“Mohammed began a political movement in Mecca. He was obviously a brilliant man, and he learned from other traditions.

“In the beginning, he’s organizing people. He’s accommodating, peaceful, tolerant, accepting of diversity because he’s organizing people with a new idea. The Qoranic verses from that period are very useful to Muslim liberals today.

“Later, in Medina, Moham-med is at the helm of power and an army. At that point, the verses go through a dramatic, prescriptive change.”

Farhang said, “It’s painful to say that in Iraq under Saddam Hussein — which was a fascistic regime — religious minorities, particularly Christians, had more freedom and security than they do today.

“In the same way, in Egypt under Mubarak, [Christian] Coptics, which make up about 10 percent of the population, had more security under dictatorship.

“Why? Autocratic states just want submission from you. If you’re not interested in politics, they don’t give a damn about you. Whereas a totalitarian state, whether rightist or leftist or Islamist or atheist, they want to make a new human being out of you. They become interested in your private space.

“What happens in your home, in your personal relations, it becomes an issue for the state.”

Farhang said, “All traditional cultures face the challenge of increasing plurality of lifestyles and values. And it doesn’t always translate to Western influence — it simply means that certain values, such as equality, are universal.

“I genuinely believe that pluralism is inevitable. I think sooner or later, this one-dimensional way of being and doing is on its way out.

“The women’s movement in Iran, for instance, is fantastic, and it shows in the number of novels written by women authors. Just as in the Western world, the taboos were first and foremost deconstructed in literature, because in literature it’s more acceptable—more so than in an essay in The New York Times.”

He said, “Democracy can’t be imposed by force, as America has demonstrated. Yet Islamist states believe that, through indoctrination, through propaganda, they can impose a value orientation on you. The Communists tried it in the Soviet Union; the Maoists tried it in China. It was a disaster. Sooner or later, those regimes break up.

“I’m pretty much convinced that whether it’s 10 or 20 or 50 years, the traditionalists are going to be marginalized, and modern values are going to be accepted by the general people because it is more natural. Equality is more natural than slavery. Equality between men and women is natural.

“It doesn’t mean that it will easily be translated into behavior or action. But for the very first time, instead of talking about imperialism or colonialism or conspiratorial theories — those things are also there — but young people, particularly women, are more and more attracted to human rights discourse, and trying to adopt human rights norms and values to their own local traditions.

“This is perhaps contrary to what you watch on television — most of which is very true, very painful and which is very tragic. But this is the price that Middle Eastern people have to pay if they want to live in a more civilized and tolerant world. And I think they’re paying it.”