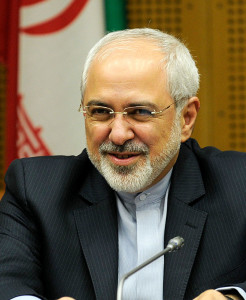

The Newsmakers of the past year selected by the editors of the Iran Times are, from within Iran, Foreign Minister Mohammad-Javad Zarif and, from the Diaspora, Ghoncheh Ghavami, who found herself in jail for the crime of trying to attend a volleyball match.

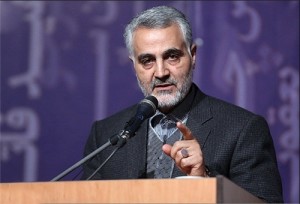

The runners-up selected by the editors are, from within Iran, General Qasem Soleymani, commander of the Qods Force, and from the Diaspora, Man Haron Monis, who turned Australia topsy-turvy in December by launching a 17-hour hostage episode in downtown Sydney.

At the end of each year, the editors of the Iran Times sit down and run through the

pages of the previous 51 issues noting who consumed the greatest amount of space in the “news hole,” whether for good or for ill.

Sometimes it’s a close call, as some figure makes a great deal of news for a short while, but then not at all for many months.

But this year, there was no question about the dominance of the news pages by Zarif all 52 weeks as he tried to barter a nuclear agreement with the Big Six that will remove Iran’s pariah status and, not incidentally, lift the sanctions that have battered Iran’s economy.

Around the world, he has been seen jetting in and out of world capitals and smiling broadly for the cameras—the photos substituting for hard news as little has been said about the substance of the talks. It could be said that Zarif made news by not making news all year.

Inside Iran, he sometimes seems to have a large target painted on his back at which hardliners aim political darts designed to scuttle the talks. He makes news inside Iran as he is forced to defend the very existence of talks on an almost daily basis.

Zarif is the up-front diplomat, but his success or failure will be decided by Supreme Leader Ali Khamenehi and no one else—not even President Obama. The question not yet answered is whether Zarif can convince Khamenehi to make the concessions needed for the Americans to sign on to an agreement.

There have no news stories at all about the conversations Zarif has had with Khamenehi, but those conversations are certainly more important than the highly publicized ones Zarif has with US Secretary of State John Kerry.

From the Diaspora, the editors named Ghoncheh Ghavami, an Iranian-born British citizen who received global attention when she was jailed for trying to get into a volleyball match as a spectator, despite Iran’s ban on women in soccer and volleyball stadiums.

The editors suspect the great attention her case received internationally was caused in part by the fact that she is a very attractive woman and many editors liked an excuse to run her picture. Ghavami received far more news coverage than another British-Iranian woman who is not nearly as attractive but who received an astounding sentence of more than 20 years for using Facebook, where she wrote that the regime was “too Islamic.”

The uproar over Ghavami eventually proved too much for the Judiciary. It allowed her out of jail on bail. But she has not been allowed to leave Iran. The regime probably achieved what it wanted. After her release, the international news coverage of her case instantly halted.

As the runner-up from within Iran, the editors chose the commander of the Qods Force. Soleymani, 58, has been in that post for more than 15 years. Americans have written about him as the eminence grise behind attacks on American troops in Iraq. But there were few stories about him in the Iranian media until last year.

The Iraqi media said he was active trying to keep Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki in that post. When Grand Ayatollah Ali Sistani said Maliki had to go, Soleymani slinked away from Iraq. There were reports in Tehran that he had been removed from command of the Qods Force. But it was soon apparent those reports (not embraced by the Iran Times) were wrong. Not only did Soleymani keep his job, but he also suddenly became a poster boy for the regime.

He started giving public speeches and his picture frequently appeared in print. His stature soared in the past few months as he helped organize and direct Iraqi militia bands in attacking the forces of the Islamic Republic and in retrieving more and more real estate the Islamic State had occupied last summer.

In Iran, he has been treated as a savior, the military leader on a white steed. In the Arab world, however, he is seen by many as the point man of a Shiite effort to seize the Islamic world.

As the runner-up from the Diaspora, the editors named Man Haron Monis, a rather odd character who moved to Australia two decades ago and tried to get a great deal of Australian news attention by such acts as chaining himself to the fences at two state capitals. He made all sorts of statements to the media, often contradicting himself from one day to the next. But he was largely ignored until he started sending letters to the widows of Australian troops killed in Afghanistan, saying their husbands were killers.

Last year, he announced that he was converting to Sunnism and joining the Islamic State. He issued inflammatory comments about Shiism. Then he walked into a Sydney cafe in December, took 17 people hostage, and issued assorted demands that were ignored. After 17 hours, he shot the cafe manager in the head and police charged into the shop, shooting Monis dead.

There was considerable fear in Australia that he was a terrorist dispatched by the Islamic State to cause chaos. But the investigations to date indicate he never had any contact with the Islamic State and was a sick man desperate for attention. In the final 17 hours of his life, he got it in spades.