February 28, 2020

The Majlis elections turned into a conservative landslide with Principleists taking a majority across the country and winning every single one of the 30 seats from Tehran but the voter turnout was the lowest by far of any Majlis election under the Islamic Republic.

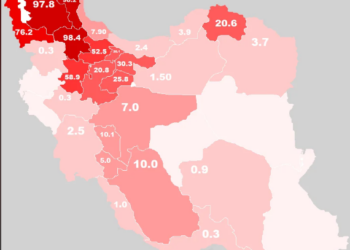

The Interior Ministry said the turnout was 42.6 percent, the first time turnout had fallen below 50 percent and almost a third lower than four years ago at the last Majlis election, prompting many to say that the “winner” was really the boycotters. But Supreme Leader Ali Khamenehi, speaking after the voting but before the Interior Ministry announced the stunningly low turnout, lauded the people’s “huge participation” in the voting.

The Tehran results totally reversed the outcome of four years ago, when Reformists took every single seat in the capital. And the turnout in Tehran was just 25 percent this year.

The Mehr news agency said that 220 of the 290 seats would be held by conservatives.

The national landslide for the right appeared to be based on at least five things.

First, the Council of Guardians, which must approve candidates for them to be put on the ballot, gutted the ranks of the Reformists by kicking most of them off the ballot. For example, in Tehran only three Reformists most people had ever heard of were approved to run. In many constituencies around the country, there was not a single Reformist among dozens of approved candidates.

Second, the call for a boycott by Reformists was loud and resonant this year, unlike in past years. The main Reformist organization for the first time supported the boycott call by declining to present a list of endorsed Reformists candidates. Then, just three days before the balloting, it issued an endorsement list, possibly at the insistence of former President Mohammad Khatami, who opposes a boycott. But by that time, the idea of a boycott had pretty much been cemented in the public’s mind.

Third, strong feelings of nationalism may have helped boost the conservative turnout as many people standing in line to vote carried photographs of the late Maj. Gen. Qassem Soleymani.

Fourth, Reformist voters were clearly disenchanted with the current Majlis, which is widely seen as a do-nothing body. Many said the Reformists hadn’t done anything in their four years in power.

Fifth, the regime has so marginalized the Majlis that it has become an irrelevancy and many Reformist voters said they see no point in voting even if there were a real slate of Reformists candidates. This gutting of the institution became most clear in November, when the Majlis, which has set fuel prices in the past, was completely bypassed. Supreme Leader Ali Khamenehi set up a new body comprised of the heads of the three branches of the government—President Hassan Rohani, Majlis Speaker Ali Larijani and Judiciary Chairman Ebrahim Raisi—and it decided to triple the price of gasoline. The Majlis was shut out of the process.

The view that voting is useless was summarized by Mehdi, a Tehran businessman in his 20s, who told CNBC, “I’m not going to vote and none of my friends is going to vote either. Nothing is going to change with or without us voting. They decide everything for the country, without considering the Majlis. So, it’s a joke to even have a parliament. We’re protesting against them by not participating in the elections.”

Sanam Vakil, of the Chatham House think-tank in London, said, “Voting doesn’t really result in policy changes that help ordinary Iranians. It’s really just about legitimizing the Islamic Republic as part of a public relations stunt rather than having a policy impact. And maybe by not voting, they are making as much of a point as if they were voting. It’s a protest in itself.”

Supreme Leader Ali Khamenehi tried to counter that idea. Three days before the balloting, he said, “Voting is a religious duty.”

The official turnout statistic released by the government was 42.6 percent, which was the lowest of the 11 Majlis elections held since the revolution and the first time the government admitted the turnout dropped below half the eligible voters. Turnout, by the official statistics, previously ranged from a high of 71.1 percent in 1996 to a low of 51.2 percent in 2004, a year when Reformists were also disqualified en masse. The average for the previous 10 Majlis elections was 60.5 percent.

In Tehran, reporters noted many long lines outside voting places in south Tehran, but then went to north Tehran where they often found no lines at all.

Some conservatives blamed the low turnout on a rumor being passed around social media that the ink used to identify voters had been infected with the coronavirus, a rumor they blamed on the United States. Election headquarters responded by saying early on Election Day that voters need not provide their fingerprints if they did not wish to. The inked fingers are one way election officials prevent people from voting twice, so the decision by election headquarters could have prompted multiple voting.

After the election, Khamenehi charged that Iran’s “enemies” had exaggerated the coronavirus outbreak intentionally to impact the election turnout. “Their media did not miss the tiniest opportunity to dissuade Iranian voters by resorting to the excuse of disease and the virus,” he said. But the foreign media only reported what the Iranian Health Ministry said, and it was the Health Ministry that announced two days before the balloting that two elderly men had died in Qom of coronavirus.

The day before the voting, the United States slammed the election as a sham and imposed sanctions on the five members of the Council of Guardians who comprised that body’s election committee and who kept most Reformists off the ballot. The leading figure sanctioned was 92-year-old Ahmad Jannati, the secretary of the Council of Guardians and the senior right-winger in the establishment.

Jannati, never known as a wit, laughed off the sanctions, saying, “I wonder, what are we going to do about all that money we have in American accounts. Now we can’t even go there for Christmas.” The sanctions block any assets the sanctioned person has in the United States, disallows them from receiving visas and bars Americans from doing business with them.

Despite the low turnout shown by its own statistics, the regime pretended the turnout was high. As it does at every election, the election headquarters extended voting hours beyond the normal 6 p.m. closing for two hours, then a couple more times until the closing was at midnight, as usual.

Interior Minister Abdol-Reza Rahmani-Fazli said the turnout was “completely acceptable,” attributing the drop in turnout to the major snowstorm hitting many parts of the country, the coronavirus outbreak and the crash of the Ukrainian passenger jet. He did not mention the many public calls from Reformists for a boycott or the denial of spots on the ballot for Reformists by the Council of Guardians.

There was even an effort to get Reformists to vote. The Islamic Republic News Agency (IRNA), the state-owned news agency, carried a story on the morning of Election Day saying former President Mohammad Khatami had voted. Since 2015, the regime has barred any news outlet from even mentioning Khatami or running his photo. This one-time exception was clearly meant to tell Reformists that the leader of their movement did not agree with the boycott.

But social media showed many prominent figures calling for a boycott, including Mostafa Tajzadeh, who as deputy interior minister ran the elections in 1998, 1999 and 2000, and Narges Mohammadi, a human rights activist currently in prison.

The western media chiefly focused on the fact that the Council of Guardians had declined to approve 55 percent of the 16,033 people who registered to be candidates. Since the vast majority of those wannabees could only characterized as nobodies, their elimination from the ballot was no loss. The real problem with what the Guardians did was its gutting of the ranks of Reformists and moderates. Of 247 incumbent Majlis deputies who registered to run again, the Guardians vetoed the candidacies of 92 or 37 percent. These were all people the Guardians approved as candidates four years ago.

Most of those axed were Reformists and moderates, though some conservatives also found themselves out in the cold.

Some Reformists have asserted that they had no candidates to even contest 230 of the 290 seats in the Majlis, though some think that number is exaggerated. A final count on the number of Reformists who won was not available as of press time. In the current Majlis, Reformists and moderates are the largest single bloc but do not hold a majority; they have about 40 percent of the seats.

Only three Reformists who are widely known were left among the 1,453 candidates approved to run for Tehran’s 30 seats. They were Majid Ansari, 65, a cleric who was a member of the Majlis from 1980 to 2004 and was a vice president under both Presidents Khatami and Rohani, Alireza Mahjub, head of the Workers House and a major labor leader, and Mostafa Kavakebian, who was leader of the rump group of Reformists in the Majlis from 2008 to 2012.

The brief, one week, election campaign was lackluster, to put it mildly. When the campaign officially started, most newspapers devoted more front page space to the giant snowstorm that battered many parts of the country. (See story on last page.) As usual, the key to the election was the endorsement lists issued by various groups. Many voters could be seen at the polls copying names from a list onto their ballots. (Ballots in Iran do not include the names of candidates. They only have blank lines equal to the number of seats in that constituency. Voters must write down the names of their choices, which sometimes causes problems with handwriting and when candidates have similar names.)

While the Reformists and moderates had trouble finding candidates, the conservatives had the opposite problem—a profusion of wannabees that often resulted in verbal brawls.

The main list of Principleists was created by Shana, the Persian acronym for the Council for the Coalition of Revolutionary Forces. Its list in Tehran was headed by former Tehran Mayor Mohammad-Baqer Qalibaf. He came in first in Tehran and is expected to become the new speaker, replacing Ali Larijani, who is retiring. The surprise, however, was that the Shana list did not include any hardline, ultraconservatives affiliated with Ayatollah Mohammad-Taqi Mesbah-Yazdi, the shining light of the farthest right.

Qalibaf, however, rejected the Shana list, not for excluding the Mesbah-Yazdi crowd but because it failed to include candidates who understood the economy and could address the main issues before the Majlis. The Shana list had been put together by former Majlis Speaker Gholam-Ali Haddad-Adel and former Tehran City Council Chairman Mehdi Chamran. After Qalibaf’s criticism, they revised the list—but still did not include people from Mesbah-Yazdi faction.

The Mesbah-Yazdi crowd then issued its own endorsement list, called Peydari, which excluded Qalibaf entirely. Peydari is backing Morteza Agha-Tehrani for speaker.

A group of supporters of former President Mahmud Ahmadi-nejad then put together their own list of endorsees called the People’s Coalition.

The Shana list prevailed in Tehran. It will take awhile to sort out all the winners from the provinces and to see how the lists other than Shana did and how much or how little support Qalibaf will have nationally.

While the regime is dominated by clergymen, the Majlis has moved from largely clerical in the 1980s to hardly clerical at all now. The Interior Ministry said that only 6 percent of the approved candidates were clerics while another 6 percent have AA or BA degrees and 88 percent advanced degrees.

A candidate must have at least 20 percent of the vote to win election. In those constituencies where there were large numbers of candidates and enough did not pass the 20 percent hurdle to fill all the seats, a run-off election involving the top two candidates will be held April 17. The Fars news agency said there would be run-offs in 11 constituencies.

In addition to voting for 290 Majlis deputies, voters in five provinces were voting to fill seven vacancies in the 88-cleric Assembly of Experts, which has mostly aged men as members and a high death rate. The assembly elects a new Supreme Leader when that post falls vacant.