November 14-2014

More than two years after a shopping mall in Ontario collapsed, killing two women, Ontario police are still trying to build a case against the Iranian-Canadian owner of the mall, Asadoor “Bob” Nazarian.

The focus now appears to be on documents that were seized from Nazarian right after the collapse but which have been under court seal ever since. The Ontario Provincial Police (OPP) are seeking access to those documents.

Three search warrants executed by the OPP pinpoint Nazarian as a prime suspect in the ongoing criminal probe of the June 2012 Algo Centre cave-in.

According to the warrants, revealed earlier this month by Maclean’s Magazine, Nazarian is being investigated for potential criminal negligence causing death for failing “to maintain the structural integrity” of the mall and failing to “take sufficient steps to remedy known deficiencies” in the building’s notoriously leaky rooftop parking lot.

Two and a half years after the fatal collapse in remote Elliot Lake, the 69-year-old Nazarian has not been charged.

To date, police have interviewed at least 800 witnesses and collected enough evidence to fill a 10-terabyte hard drive, Maclean’s reported. But so far charges have been filed against only one person, a former engineer. The case against Nazarian appears to hinge on more than 700 documents that remain off-limits to police because his lawyer, Antoine-Rene Fabris, claims lawyer-client privilege.

In July, the Ontario Attorney General’s office asked a judge to “review the seized documents in order to resolve and rule upon the issue” of whether they are indeed privileged. Not all correspondence between a lawyer and client is automatically covered by privilege; only those records that specifically discuss legal advice, litigation or settlements are confidential.

On October 15, the Elliot Lake Public Inquiry issued its report, a sweeping, indictment that implicated a long list of characters, from shoddy inspectors to bumbling city officials to successive owners who knew the roof was a potential structural risk but refused to pay for repairs. As Commissioner Paul Belanger concluded: “The real story behind the collapse is one of human, not material, failures.”

The 1,400-page report concluded that municipal officials protected the crumbling mall because the building was considered vital to Elliot Lake’s “Retirement Living” strategy.

But Maclean’s asked, “If so many were ‘greedy,’ ‘negligent’ and ‘incompetent,’ why haven’t police laid more criminal charges?”

The search-warrant records obtained by Maclean’s indicate that only two people—Nazarian and the engineer—have been fingered by police as suspects.

Police seized thousands of documents from dozens of locations in the weeks after the tragedy, including files from City Hall, Retirement Living, Algoma Central Corporation (the company that built the mall), and numerous engineering firms.

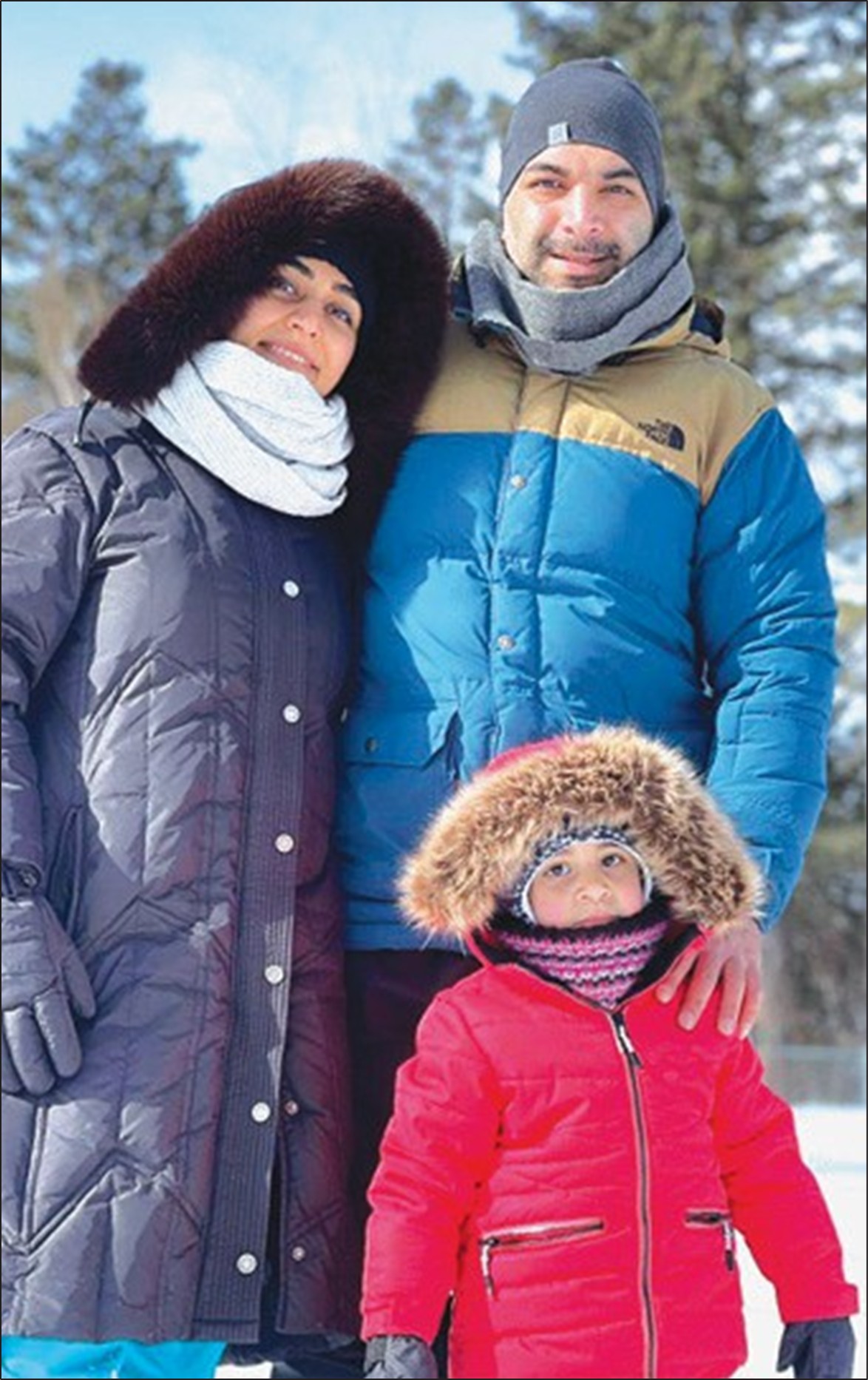

Investigators also raided Nazarian’s home in Richmond Hill, the suburb of Toronto where the region’s Iranian expats have congregated.

“I reasonably believe that an examination and analysis of these [digital storage] devices will afford evidence in relation” to the offence of criminal negligence causing death, wrote Detective-Constable James Hambleton, a member of the investigative team.

As police raided Nazarian’s properties, his lawyer, Fabris, claimed privilege over every document with his letterhead. Those records were therefore packaged separately and closed with “forensic seals.” A representative of Fabris’s law firm later visited the OPP evidence locker in Elliot Lake, examined each document, and claimed privilege on 738 pages. To this day, police are still prohibited from reading them.

A sworn affidavit signed by Det.-Const. Allan Gelinas in August 2013 says, “To date, investigators have identified two suspects in the Algo Centre Mall investigation, Bob Nazarian (the owner of the mall) and Bob Wood (the engineer who conducted the most recent inspection of the mall).”

Wood was arrested five months later, in January 2014, and released pending trial. A once-respected engineer with nearly 40 years of experience, he inspected the mall just 10 weeks before the roof gave way and concluded that the steel beams supporting the rotting parking deck were “structurally sound.”

In his inquiry report, Commissioner Belanger compared Wood’s review “to that of a mechanic inspecting a car with a cracked engine block who pronounces the vehicle sound because of its good paint job.”

Maclean’s said Wood agreed to alter his final report, at Nazarian’s request, to remove a photo of a severely rusted beam and a reference to “ongoing” leakage. Wood faces two counts of criminal negligence causing death and one count of criminal negligence causing bodily harm.

Building a possible criminal case against Nazarian, however, has proven far more complicated because of the privilege issue. The Nazarian family (Bob, his son Levon, and his wife Irene) all refused to turn over tens of thousands of emails, forcing the inquiry commission to go to court demanding access. Although the Nazarians eventually relented and handed over most of the records, they continued to claim privilege on 289 specific documents.

In the end, Justice Stephen Goudge of the Ontario Court of Appeal ruled that only a small minority of the records were privileged, and ordered the rest handed over to the inquiry.

But, Maclean’s commented, “for police immersed in their own investigation, confusion reigned: prohibited from looking at the sealed documents in their possession, the OPP has no idea if they are the same ones disclosed to the inquiry, or if they even hold any evidentiary value.”

Whatever the outcome of the haggling over the documents, the larger question remains: Why just Wood and Nazarian?