January 24-2014

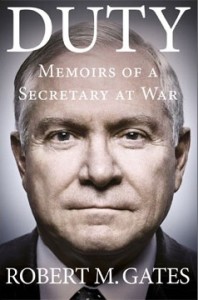

Former Defense Secretary Robert Gates writes that President George W. Bush never gave a thought to attacking Iran while Gates was defense secretary the last two years of the Bush Administration.

Much breathless media coverage during that period—especially from the London press and the leftwing media—spoke as if Bush were plotting a war that was imminent.

In his new book, “Duty: Memoirs of a Secretary at War,” Gates says the Bush Administration worried that Israel might attack Iran on its own and suck the United States into a war. And it worried about that even before Binyamin Netanyahu became prime minister of Israel. But the Bush Administration was never scheming for a war itself.

Gates writes that Vice President Dick Cheney advocated ending the Iran problem before the Bush term expired, but says Cheney had no support in the White House.

Gates was defense secretary for the last two years of the Bush Administration and for the first 2 1/2 years of the Obama Administration, from December 18, 2006, to July 1, 2011. His book will appear in bookstores next month.

Gates was defense secretary for the last two years of the Bush Administration and for the first 2 1/2 years of the Obama Administration, from December 18, 2006, to July 1, 2011. His book will appear in bookstores next month.

As defense secretary, Iran was a major issue for Gates, but far from the major issue. Only 41 of the 600 pages in his memoir are primarily about Iran.

Gates reveals that he was involved with Iran from the first days of the Islamic Republic and long before he became defense secretary. When Zbigniew Brzezinski, President Jimmy Carter’s national security adviser, met with Prime Minister Mehdi Bazargan and Iran’s revolutionary foreign and defense ministers in the fall of 1979 in Algeria, Gates was the notetaker in the room.

Brzezinski “offered recognition to the revolutionary regime,” Gates writes, although official regime rhetoric has said for 30 years that the United States refused to recognize the revolution.

Brzezinski “offered recognition to the revolutionary regime,” Gates writes, although official regime rhetoric has said for 30 years that the United States refused to recognize the revolution.

Gates writes that Brzezinski “offered to work with them and even offered to sell them weapons we had contracted to sell to the Shah…. The Iranians brushed all that aside and demanded that the United States return the Shah….. Both sides went back and forth with the same talking points until Brzezinski stood up and told the Iranians that to return the Shah to them would be ‘incompatible with our national honor.’ That ended the meeting.” Three days later the US embassy was seized and Bazargan and his cabinet were out of office.

Gates was a career Soviet analyst with the CIA, but at that time he was assigned to the staff of the National Security Council in the White House. He remained there when Ronald Reagan succeeded Carter. He writes that throughout the Iran-Iraq war, “the US approach during the Reagan Administration was ruthlessly realistic—we did not want either side to win an outright victory; at one time or another we provided modest covert support to both sides.”

Official state rhetoric in Iran insists that the United States put Iraq up to invading Iran and funded and armed it for all eight years of the war. Iran never mentions the anti-tank missiles and radar equipment Iran got from the US in what became the Iran-Contra scandal.

. . . on cover of his book

When Gates became defense secretary under Bush, all options were on the table with regard to Iran—at least rhetorically. Gates said, “One thread running through my entire time as secretary was my determination to avoid any new wars while we were still engaged in Iraq and Afghanistan…. Were we faced with a serious military threat to American vital interests [from Iran], I would be the first to insist upon an overwhelming military response. In the absence of such a threat, I saw no need to go looking for another war.”

Gates writes: “I therefore opposed military action as the first or preferred option to deal with the Syrian nuclear reactor, to deal with Iran’s nuclear program, and later, to intervene in Libya. I was convinced Americans were tired of war, and I knew firsthand how overstretched and stressed our troops were. There were those inside the Bush Administration, led by Cheney, who talked openly about trying to resolve problems—like ours with Iran—with military force before the end of the administration….Bush fortunately opposed such actions.”

Gates devotes much of the space in his discussion of Iran to his meetings with Israeli and Saudi leaders, who he said were lobbying hard to get the United States to tackle Iran militarily. The Israeli media revealed that government’s efforts, but the Saudis leaked stories saying that Riyadh was exasperated with Washington’s propensity to use military force.

Gates says he first sat down with Saudi King Abdullah in July 2007. “He wanted a full-scale military attack on Iranian military targets, not just the nuclear sites,” Gates writes with surprise. Gates said he was incensed at Abdullah. “He was asking the United States to send its sons and daughters into a war with Iran in order to protect the Saudi position in the Gulf and the region, as if we were mercenaries.”

Gates also complains that Abdullah was wary of any overt military planning with the United States that he feared might provoke Iran against Saudi Arabia.

Gates says that Cheney advocated either attacking Iran with US forces or empowering the Israelis to do the job themselves. Gates said his own bottom line was that there was no need to do anything at that time. US intelligence said Iran was nowhere near developing nuclear weapons. The military option did not need to be exercised at that time and was probably good for years to come, Gates argued.

He said that at one point Israel asked for a huge range of weapons that included everything they would need to pull off an attack on Iran. Gates said he recommended that Bush say no because otherwise he would “signal US support for them to attack Iran unilaterally.” The president said no.

Gates writes: “I think my most effective military argument, and one that even the vice president came grudgingly to acknowledge, was that an Israeli attack that overflew Iraq would put everything we had achieved there with the surge at risk—and indeed the Iraqi government might well tell us to leave immediately.” Iraq at that time had no air force and it was the US Air Force that patrolled Iraqi skies. The US Air Force would have to allow any Israeli attack by ceding it Iraq’s airspace.

Gates says he first dealt with Netanyahu in the 1980s when Gates was on the National Security Council staff and Netanyahu was deputy foreign minister. Netanyahu “called on me in my tiny West Wing office,” Gates writes. “I was offended by his glibness and his criticisms of US policy—not to mention his arrogance and outlandish ambition—and I told National Security Adviser Brent Scowcroft that Bibi [Netanyahu’s nickname] ought not be allowed back on White House grounds.” That was surprisingly strong and impolitic language to use in a book published while Netanyahu is a sitting prime minister.

Gates was asked by President Obama to stay on in office, and he agreed to do so. Gates discusses Obama’s effort to engage with Iran. He mentions the two letters Obama sent to Supreme Leader Ali Khamenehi after entering the White House. Most previous reports have said the two letters were never answered, but Gates says both were answered, although the answers were nothing but “diatribes.”

Gates says he strongly supported the Obama approach to Iran for talks. “I thought that when it failed—as I believed it would—we would be in a much stronger position to get approval of significantly stricter economic sanctions on Iran at the UN Security Council. That turned out to be the case…. I underestimated the reaction to the initiative from the Israelis and our Arab friends, both of whom nurtured the dread that the United States would at some point cut a ‘grand bargain’ with the Iranians that would leave both Israelis and Arabs to fend for themselves against Tehran.”

Gates makes one point that is very relevant to US relations right now with Russia. The Russians have long opposed the US plan to install anti-missile missiles in Eastern Europe to knock down any Iranian missiles that might be fired over Europe. Since the interim nuclear agreement was signed with Tehran in November, the Russians have been saying repeatedly that the missiles are no longer needed.

Gates wrote that Obama wrote Russia’s president that the need for missiles in Europe would be removed if the Iranian nuclear issue were resolved. He said that while some conservatives squawked about that, it was the same message that Gates and Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice had conveyed to Russia in the Bush Administration.

Gates tells of a meeting he had with Netanyahu in July 2009. Netanyahu continued to push for an air attack on Iran’s nuclear plants—though not on all of its military targets, as Saudi King Abdullah had urged on Gates the year before. “Bibi was convinced the Iranian regime was extremely fragile and that a strike on their nuclear facilities very likely would trigger the regime’s overthrow by the Iranian people.” This was the logic that reportedly convinced Saddam Hussein to invade Iran in 1980.

Gates told Netanyahu, “I strongly disagreed, convinced that a foreign military attack would instead rally the Iranian people behind their government.” That was what happened in 1980 when the Iraqi invasion bolstered a government that was weak and unstable.

Gates makes only a very brief reference to discussing Iran with Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan. He says Erdogan “was just too wary of anything that might provoke the Iranians.”

Gates says the key change in Obama policy toward Iran came in late 2009 when Iran walked away from a proposal to have its enriched uranium shipped out of the country and converted to fuel for the Tehran research reactor that could not be used to make bombs. Gates said Obama chaired a meeting of the National Security Council on November 11, 2009, at which he said “we had to pivot from engagement to pressure.” It still took another two years to mobilize the EU member states to slam the door on the Islamic Republic with punitive sanctions.