November 10, 2017

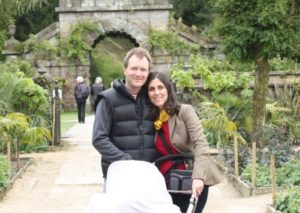

For a long time, Richard Ratcliffe has demanded that the British government condemn Iran’s arrest of his wife. Last week, Foreign Minister Boris Johnson finally did as asked—but then he made everything worse by saying that Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe was doing just what Iran accused her of doing—training journalists.

The Iranian Judiciary then brought her back into court Saturday and threatened to increase her sentence. Her husband said she was told that her five-year sentence would be doubled if she were found guilty as a repeat offender. But there could be no repeat offense; she has been in prison ever since her conviction. Her husband said she was shown a dossier that contained only the same evidence and charges made at her first trial.

Foreign Minister Johnson immediately under pressure to rescind what he said last week. But the Foreign Office issued a statement that actually stood by what Johnson said.

Finally, on Tuesday, Johnson called Foreign Minister Mohammad-Javad Zarif to try to rectify matters. In a statement issued after his call, Johnson said his remarks to parliament “could have been clearer,” though he still refused to rescind his comment that Zaghari-Ratcliffe had been teaching journalists. The statement said Johnson expressed concern that Iran’s Judiciary believed his remarks “shed new light” on Zaghari-Ratcliffe’s case. Johnson said that “was absolutely not true.” The statement said Johnson would go to Iran before the end of the year to discuss the case with Iranian officials.

Johnson’s original remarks threatened to make life much harder for Zaghari-Ratcliffe. But they made life—political life, that is—harder for Boris Johnson. He is touted as a likely successor to a rapidly weakening Prime Minister Theresa May. If he now emerges as a clumsy oaf who hurts the people he is supposed to help, it might kill his chances to move into Number 10 Downing Street.

The Foreign Secretary has long been criticized by many people, not just Richard Ratcliffe, for failing to condemn the jailing of Mrs. Ratcliffe, who has been held since her arrest by the Pasdaran in April 2016.

But, speaking to a committee of MPs last week, Johnson finally condemned both her conviction for spying as a mockery of justice and her treatment by the authorities in Tehran.

In his testimony, he said, “When I look at what Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe was doing, she was simply teaching people journalism, as I understand it.”

Zaghari-Ratcliffe was then summoned to court Saturday, where Johnson’s comments were cited as proof that she was engaged in “propaganda against the regime.”

The Judiciary’s High Council for Human Rights said Johnson’s comments proved Zaghari-Ratcliffe “had visited the country for anything but a holiday.” Her family has said she was in Iran on a private visit to show her 22-month-old daughter to relatives.

This week, Zaghari-Ratcliffe’s employer, Thomson Reuters Foundation, repeated that she had not gone to Iran on an assignment but was on vacation. Chief executive Monique Villa said Zaghari-Ratcliffe “is not a journalist and has never trained journalists at the Thomson Reuters Foundation,” where she works as a project manager. Thomson Reuters Foundation is the charitable arm of the news agency.

Villa urged Foreign Minister Johnson to correct his “serious mistake,” saying it “can only worsen her sentence.”

The foundation has also said numerous times that it doesn’t have any projects in Iran.

In the statement issued after the brouhaha first arouse last week, Britain’s Foreign Office didn’t modify Johnson’s words, but only said his words “provide no justifiable basis on which to bring any additional charges against Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe.”

It said, “While criticizing the Iranian case against Mrs. Zaghari-Ratcliffe, the foreign secretary sought to explain that even the most extreme set of unproven allegations against her were insufficient reason for her detention and treatment.”

Last month, before Johnson’s verbal stumble, Zaghari-Ratcliffe was told she could face 16 more years behind bars after the Iranian courts reopened her case and added three new charges.

Johnson’s condemnation of Iran in his parliamentary testimony came despite his own warning that “very loud public campaigns” to free UK nationals held in Iran can easily backfire. “That simply strengthens the hand of those who are using this case for their own internal ends in Iran,” he told the parliamentary committee.

“That’s why sometimes the advice I have had over the months is that no matter how frustrating or miserable it is – and clearly these cases are very, very sad – the best approach is a diplomatic one.”

The Foreign Secretary commented that previous noisy American protests had seen “the Iranians lift [detain] some more [Americans] and hold them for the same purposes.”

It isn’t clear that either a policy of silence or one of condemnation actually makes any difference. At the moment, Iran is known to be holding seven Americans and four Britons. In addition, there are two from Canada and one each from France, Austria, Sweden, the Netherlands, Cyprus, Denmark and Germany. Apart from the US, only Sweden has been vocal—and that only began last week. Two of those detained are legal permanent residents of foreign countries (the US and Sweden), while the others are all dual nationals.

Two people—Iranian-Canadian Homa Hoodfar from Montreal and Iranian-American Hamed Ghassemi from Louisiana—have been freed since the January 2016 Iran-US prisoner swap. But none of the detained Britons has been freed.

Many arrests are not announced and there may well be others detained in Iran.

At the parliamentary committee hearing, chairman Tom Tugendhat asked Johnson if “the Iranians are hostage takers.” Johnson said: “I’m not going to go as far as to say that.”

Responding to Johnson’s comments before the parliamentary committee, Ratcliffe said: “I warmly welcome the Foreign Secretary’s condemnation of Nazanin’s treatment by the Iranian authorities to date. He is right – her case is a mockery of justice, and an abuse of Iranian and international law.”

Ratcliffe explained that Johnson’s comment about his wife having taught journalism appeared to be a bungled description of her first job after university eight years ago when she was an assistant at BBC Media Action, the corporation’s international development charity.

He said that his wife had never taught journalists, but simply made travel arrangements for tutors on an international journalism course.

Ratcliffe said then, “The worst thing the Foreign Secretary could do is to now suddenly go quiet…. You can’t make a muddle and then leave it. That would be the worst of both worlds.”