The World Bank forecasts that foreign investment in Iran will rise once sanctions are lifted but not by anywhere near as much as Iranians have been led to believe as the country proves to be less attractive than many expect.

It also calculates that oil prices will fall another 14 percent when Iran resumes pumping at its more usual rate.

A new World Bank report, titled, “Economic Implications of Lifting Sanctions on Iran,” calls sanctions relief “an economic windfall to the Iranian economy.”

But to benefit the economy, that windfall will “have to be properly managed,” the World Bank says. And it adds ominously, “Iran’s track record with past windfalls is mixed.” It then inserts an analysis of three windfalls Iran has received since the end of World War II—one under the Shah and two under the Islamic Republic—and concludes that all were bungled.

On economic growth, the World Bank is positive, seeing growth exceeding 5 percent in each of the next two years. However, that is not very impressive given that countries emerging from recessions commonly grow much faster. Iran’s GDP growth soared by 14.0 percent in 1990 and 12.3 percent in 1991 as the Rafsanjani Administration led it out of the wartime recession. So the World Bank’s estimate of 3.3 percent growth in the current Persian year and its forecast of 5.1 percent growth next year and 5.5 percent the following year are merely ordinary.

On economic growth, the World Bank is positive, seeing growth exceeding 5 percent in each of the next two years. However, that is not very impressive given that countries emerging from recessions commonly grow much faster. Iran’s GDP growth soared by 14.0 percent in 1990 and 12.3 percent in 1991 as the Rafsanjani Administration led it out of the wartime recession. So the World Bank’s estimate of 3.3 percent growth in the current Persian year and its forecast of 5.1 percent growth next year and 5.5 percent the following year are merely ordinary.

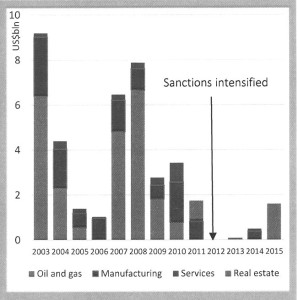

As for foreign investment, which the regime is counting on, the World Bank predicts increased foreign investment, but with levels below what prevailed before the big hit from sanctions in 2012.

Iranian officials have said they need $130 billion to $145 billion in new investment—that includes both foreign and domestic investment, not just foreign investment—in oil and gas by 2020 just to keep oil production from falling as fields age. That means an average of well over $20 billion a year.

But the World Bank forecasts new foreign investment at about $3 billion in 2016 and $3.2 billion in 2017—for the entire economy, not just the oil and gas sector.

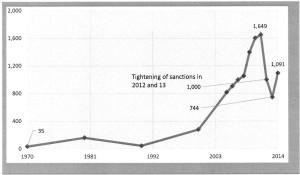

According to the World Bank, foreign investment topped $9 billion in 2003 and averaged $4 billion a year in the decade before sanctions cut foreign investment to zero in 2012. It says foreign investment this year is running at $1.6 billion for the full year.

The Bank’s report blames what some have called government-by-whim for the country’s spotty economic record. “The government’s macroeconomic policy changes frequently and is often difficult to predict, putting private actors at a disadvantage,” the Bank writes. “As a result, growth has remained below potential.”

The main economic goal of all Iranian governments has been to create jobs. But the Bank’s report doesn’t forecast good news on that front, in part because investment is going into the oil and gas sector, which gobbles up cash but does not create very many jobs.

“There are estimates that about 800,000-900,000 Iranians enter the labor market each year,” the report says. “Even before the 2012 tightening of sanctions, the economy was able to create only 200,000 jobs a year. That number has since declined substantially. As the immediate impact of removing sanctions will be increased production in the oil industry, which employs a negligible share of the Iranian workforce, the demand for labor is unlikely to be directly affected.”

It says the economy needs to create 1 million jobs in each of the next five years just to hold unemployment at 10 percent. But with an historic job creation rate only one-fifth that need, the prospects are not good.

The report warns that as oil revenues grow, the rial is likely to strengthen. That, in turn, will make Iran’s non-oil exports more expensive and less competitive in the rest of the world. One of the benefits Iran has enjoyed from the rial’s collapse has been its ability to boost a multitude of non-oil exports, which have been very cheap on world markets because of the cheap rial.

The Bank pointed out that this same thing happened in the early 2000s. “Many of the exporting industries suffered,” it said. “In fact, the only ones that made progress were the petrochemicals and chemicals industries, which received massive subsidies, including subsidies on their consumption of fuel.”

The opposite happened in recent years in the auto industry. Although Iran likes to blame the halving of auto output from 1.6 million cars in 2011 to 750,000 in 2013 entirely on sanctions, the World Bank says the bigger culprit was the rial and the fact that Iran’s auto industry—despite claims to the contrary—must import massive quantities of parts. When the rial plummeted, carmakers could no longer afford those imports.