February 07 2020

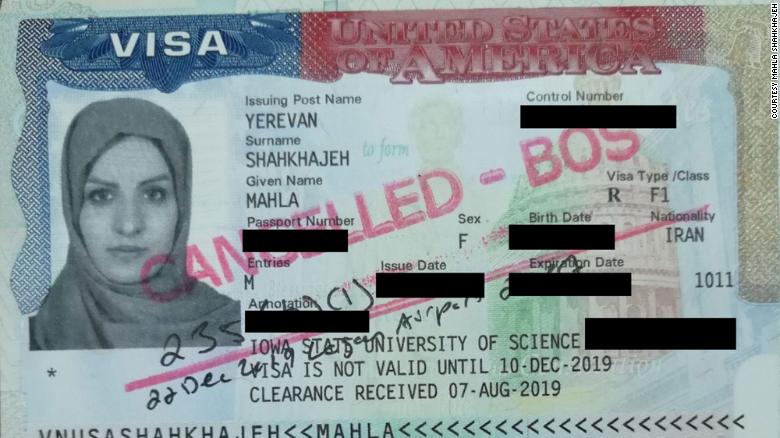

US immigration officers are suddenly deporting Iranian students with valid visas as they arrive at US airports to go to college.

A 27-year-old engineer who had planned to get a doctorate at Michigan State University was deported from Detroit Metro Airport January 27. A week earlier, a 24-year-old Northeastern University student was escorted onto a plane in Boston as protesters at the airport pushed for his release.

For the students, it’s devastating. Many have sunk thousands of dollars into coming to the United States, closed their residences in Tehran and quit their jobs.

For immigrant rights advocates in the US, it’s a troubling pattern emerging as tensions run high between the US and Iran. And for American universities hoping to convince the world’s top students to study in their classrooms, it’s causing concern—even though the overall number of cases is still relatively small.

“Campuses are much more worried about what happens at the port of entry than they used to be … because it is so unpredictable and so apparently random,” Terry Hartle, senior vice president of the American Council on Education, which represents about 1,800 colleges and universities, told CNN. “It used to be that you would breathe a sigh of a relief when your international student got their visa. Now you breathe a sigh of relief when they get to campus.”

Most people think erroneously that a US visa from the State Department gives a holder permission to enter the United States. It does not. It only gives permission to fly to a US “port of entry.” US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) rules there and decides whether a visa holder can enter.

CBP says its inspections take additional factors into account and can uncover details that didn’t come up in previous visa screenings. It also enforces laws and regulations a dozen other agencies.

There’s no guarantee, the agency says, that someone with a visa will be allowed to enter the United States. And every day, hundreds of people are denied entry at US ports.

But, “something’s different now,” Ali Rahnama, legislative counsel for the Public Affairs Alliance of Iranian Americans (PAAIA), told CNN. “Deportation of this number of students is not normal.”

At least 17 Iranian students have been deported from the US since August, according to Rahnama, who’s spoken with most of them as he tries to get a handle on what’s happening. It’s a notable increase from previous years, Rahnama says, when one or two cases would come up annually.

Advocates say many students in the recent wave of cases were deported from Boston’s Logan International Airport—at least 11 of them, by one attorney’s count.

Carol Rose says the trend is clear. But the reasons behind it, she says, remain a mystery.

“We don’t know whether this is a decision by the Boston CBP office, or whether this is a decision coming from the Trump Administration, because it’s all being done in secret,” says Rose, the executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union of Massachusetts.

Early in January, about 60 Iranian-born people trying to enter the United States at the Blaine, Washington, border crossing were stopped in one weekend. Recently, a document was leaked that showed the order to stop and question them did not come from Washington but from the Seattle regional CBP office. It was rescinded as soon as news of what was going on reached the media.

In Boston, a stink arose over one particular student, a Northeastern University undergraduate, who was held for questioning after arriving at Logan Airport and was on the verge of being deported. College students turned out to support him. They cheered when they learned a federal judge had issued an order temporarily blocking any efforts to remove him. But the order was issued just as the student was being put on a plane and he was gone before the order arrived at the airport.

A Department of Homeland Security official told CNN the student was denied entry in part because CBP officials believe his father had an affiliation with a US-sanctioned transportation company that allegedly provided weapons to Hezbollah on behalf of the Pasdaran.

But it’s not only Iran-ians who’ve been affected. Some students from other countries have also been turned back in recent months, such as a group of Chinese students who were heading to Arizona State University in September.

During interviews with CNN, several deported students and their attorneys detailed their experiences at US airports, describing what they said were hours of questioning that left them feeling exhausted and confused.

One Iranian woman said she traveled to Boston in September to begin a master’s in theological studies program at Harvard Divinity School. Once she arrived at the airport, she said CBP officials grilled her about Iran, her political opinions and an attack on a Saudi oil field that had occurred just days earlier.

“I didn’t know anything about it. I just was packing my luggage…. It was like an official inquisition. It was very strange. I’m an ordinary student. I’m not a political person or a diplomat,” she said.

After about nine hours of questioning, officials told her they were revoking her visa and sending her back to Iran. For five years, they said, she wouldn’t be able to return.

She’d quit her job. She’d turned down an opportunity to study in Europe—all for the chance to study at Harvard.

“It was a real trauma. And I’m still shocked,” she says. “It’s like, in a few hours, all of the open ways got closed for me.”