July 24, 2020

Ironically, Iran is suffering little impact from the price collapse. Since US sanctions have reduced Iran’s exports to very little, it isn’t earning much from oil exports anyhow. Most of what Iran exports goes to China, which doesn’t pay for it as its imports are repayments for a debt Iran owes it, and Syria, which is being propped up by Iran and also doesn’t pay for the oil it gets from Iran.

Iran’s export level is uncertain as Iran is trying to hide the numbers, but it is generally believed to be below 250,000 barrels a day since the start of the year, or only 10 percent of what it exported from the end of the 1980-88 war with Iraq until harsh sanctions were imposed in 2012.

Kpler, which tracks oil flows, put Iran’s exports at 254,000 barrels a day in January, 248,000 in February, 160,000 in March, but only 70,000 in April—but then rose back to 100,000 in May and 237,000 in June. However, another company said April exports may have reached as high as 350,000 barrels—an indication of how difficult it is to find out just what Iran is exporting.

But more important is how much income Iran earns from those exports—and that may be close to zero. It is trying to market oil under the radar to countries other than China and Syria—countries that pay. That oil would have to be sold at a major discount because of US sanctions, however.

In April, OPEC’s 14 members and 10 other oil producers assembled by Russia agreed to cut their output by 9.5 million barrels a day. That didn’t impress the market as the demand for oil had already dropped by 20 million barrels a day. Before the coronavirus outbreak, the world consumed about 100 million barrels of oil a day.

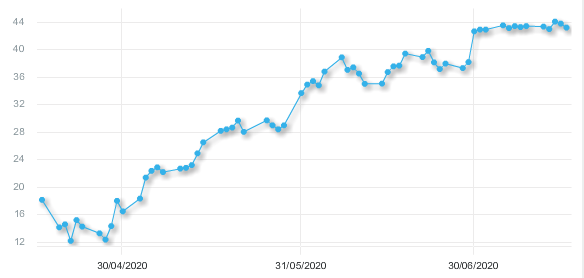

The price of an OPEC barrel plunged to a low of $12.22 on April 22, but has since been climbing back upward. Still, the price since the start of July has been around $44 a barrel and the average price so far in 2020 is $39.56. The last time the price was below $40 for a full year was in 2004.

The markets shuddered when the price fell negative one day. The importance of that was exaggerated in the media, however. The negative price—which means a producer must pay the buyer to take oil off his hands—applied only to futures contracts for one month. Futures contracts are paper transactions; they are not physical oil. On the last day in April on which futures contracts for May were traded, the price for West Texas Intermediate crude futures went negative April 20 because anyone caught with a May futures contract the next day would have to convert it to physical oil and would have trouble finding anywhere to store it, as most tanks are filled to the brim. The price that one day was -37.63.

The pricing problem began at the start of March as a feud between Russia and Saudi Arabia over production quotas.

Russia rebuffed a Saudi call to slash oil output in an effort to hold the line on prices, and Saudi Arabia angrily responded by shooting up its production and cutting down its price in a threat to every oil producer, not just Russia.

The selling price for an average OPEC barrel on the spot market fell an astounding 33 percent in two days in the second week of March to just $34.71.

Reuters called the Saudi announcement “a full-on declaration of war” on the oil market.

Iranian Oil Minister Bijan Namdar-Zanganeh called the meeting that ended with no decision on anything one of the “worst” OPEC gatherings he had ever attended.

Russia and Saudi Arabia were once joined at the hip, negotiating a production level that the Saudis would take to OPEC and impose on other members and that Russia would take to nine other non-OPEC oil producers and impose on them.

Last September, however, the Saudis dropped the oil minister who had worked out that arrangement and appointed a new minister, Prince Abdul-Aziz bin Salman Al-Saud, son of the current monarch and first royal to hold the post. He met with OPEC oil ministers early in March, then took their decision to the Russians and tried to impose it on Russia and the other non-OPEC producers.

Russian Energy Minister Alexander Novak balked, though he did not explain why. Russia agreed to nothing—not even to an extension of the current limits on production in each of the 24 oil producers that have been partners in the production limits for the past few years.

The current production limits on the 14 member states of OPEC and the 10 states in what is called OPEC+ expired March 30.

The Saudis said on March 7 that they would raise their output, which was 9.7 million barrels a day in January, to at least 10 million and possibly 12 million in April. The plan the Russians rejected would have called for the Saudis to cut output by 500,000 barrels a day.

The Saudis also announced large cuts in their posted prices for oil sales in April. The posted prices are always different for each continent; the Saudi posted prices were about $7 less per barrel than they had been previously.

While Russia was the immediate target of the Saudi anger, many thought American oil frackers were another target. Their high production the last few years has forced down prices.

Eventually, the Saudis dropped their threats to boost output and started cutting back output drastically. The corona-virus outbreak cut consumption so deeply and so quickly that the Saudis soon realized they had shot themselves in the foot by boosting output. The Saudi change of mind—accompanied by a slow climb in consumption and a slow drop in stored crude—has allowed the price to rise since April 23. Nigeria and Iraq are the two OPEC members who have cheated substantially on the deal and are overproducing, to the consternation of the Saudis.

Reuters reported that President Trump telephoned Saudi Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman April 2 and told him that if the Saudis did not cut output he would be powerless to prevent Congress from passing legislation to force US troops to leave Saudi Arabia. Ten days later, the Saudis announced they were cutting output.

The price of an OPEC barrel fell below $50 a barrel the first trading day after the Saudi-Russia spat erupted in public. On the first trading day after the Saudi threat to boost output and cut its sales prices, the price of an OPEC barrel plummeted to $34.71.

The price of an OPEC barrels had not been below $40 since August 4, 2016, or 3-1/2 years ago.