By Amir Taheri

Since 1979, when the mullahs seized power in Iran, several terms specific to their trade have entered the international political vocabulary.

One term is taqiyya which means hiding one’s true faith in order to deceive others in a hostile environment. Another term is kitman which means keeping an adversary guessing by playing one’s hand close to the chest. A third is do-pahlu which means an utterance that could have two opposite meanings at the same time. The closest equivalent in English is double-talk. In George Orwell’s novel 1984 the same concept is introduced as “doublespeak.”

For more than three decades, the mullahs and their associates have used that arsenal of deception against foreign powers and internal adversaries. What is new is that the mullahs and their associates are starting to use this against each other.

One example was furnished by President Hassan Rouhani’s visit to New York and the ripples it caused in Tehran.

In New York, Rouhani, with his Foreign Minister Muhammad Javad Zarif playing the role of Sancho Panza, tried to seduce the Americans with smiles and sweet words. Rouhani called America “Great Nation” rather than “The Great Satan.” At one point he even tried to speak a little bit of English on American TV. Then there was the much-talked of telephone call with Barack Obama during which the two men exchanged a few short words.

For his part Zarif wooed the Americans by professing his love of all things American, most notably what they call ‘football,’ not to mention insisting on sitting next to US Secretary of State John Kerry during a photo-op session.

Back in Tehran, Rouhani’s friends presented the whole rigmarole as an historic diplomatic coup. One even called it a “Divine Blessing”.

Shortly after Rouhani’s return, however, the euphoria in Tehran started to subside. The first shot was fired by “Supreme Guide” Ali Khamenei who used the do-pahlu or double-talk technique by declaring that while he endorsed Rouhani’s behavior in New York he thought that some of “the events” that took place there were “untoward”.

By not saying which “events” had been “untoward”, Khamenei opened the door for others to suggest that every move that Rouhani had made might have been that.

The trouble is that these two “untoward events” were the sole interesting features of Rouhani’s otherwise bring visit. He made a routine speech at the UN General Assembly, had dinner with a few wealthy Americans of Iranian origin, and granted a series of TV interviews during which he talked much but said little. These were exactly the same things that Mahmoud Ahmadinejad had done during seven annual visits to New York.

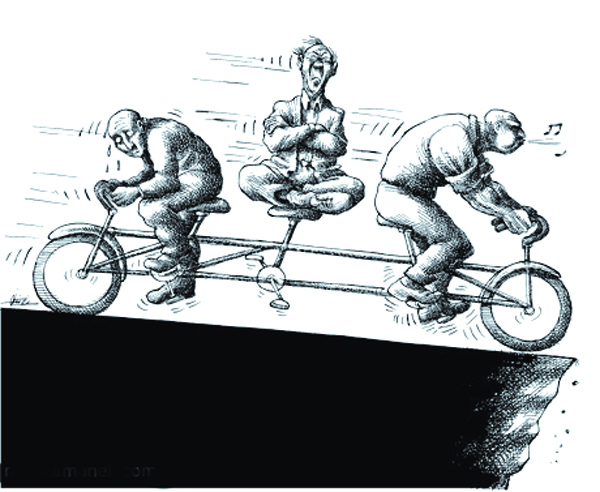

Nevertheless, the issue of Iran’s relations with the United States is too important to continue being used by rival factions in Tehran as a political football.

If Khamenei thinks that phoning Obama and sitting next to Kerry is “untoward” he should say so openly. If Rouhani thinks that such things are not “untoward” but necessary to break the ice with Washington, he, too, should say so openly.

More importantly, the Iranian people should be given a full and honest report of what happened and who took what decisions.

Khamenei’s posture is disingenuous, to say the least. If things turn out well, he could claim that he had supported Rouhani’s desperate quest for an opening with Washington. If, on the other hand, Rouhani falls on the roadside before reaching even the first stage of normalization with the Americans, Khamenei could wear that “I-told-you-so” smile. One result of this do-pahlu debate is that almost every Tom, Dick, and Harry believes they have the authority to issue statements regarding foreign policy in general and relations with the US in particular.

Khameni’s numerous advisers offer contradictory assessments of Rouhani’s endeavor, some approving, others rejecting. Even military and police officers have joined in the cacophony, violating the long-established tradition under which those in uniform do not join the political debate in public. Across the nation, mullahs delivering Friday sermons offer different readings of the events in accordance with their factional attachments. The net result is that no one could be sure who makes foreign policy in the Islamic Republic and what might emerge from the soup that Rouhani claims he is cooking. While in New York, Rouhani tried to address the issue in some of his interviews. Most notably, he noted that the powers and duties of both the “Supreme Guide” and the President were defined in the Constitution, implying that neither could go beyond limits fixed for him. He also claimed that he had the “full authority” to deal with key issues such as the crisis over Iran’s nuclear program. More importantly, perhaps, he said that the “Supreme Guide” has “his own views on some issues”, implying that Khamenei did not have the final word on all matters.

Zarif did a bit of desperate explaining of his own. He told Americans that Khamenei had accepted that the Holocaust did happen, and claimed that the website of the “Supreme Guide” had been “wrongly translated” when it stated the opposite.

Using the do-pahlu technique, Rouhani has nevertheless, raised crucial issues. If he could be second-guessed, let alone vetoed, on every move, even symbolic ones such as a telephone call, no one is going to take him seriously as a negotiating partner. Such a perception would put Rouhani in a position of weakness from the start. If he is perceived as just a messenger boy, everyone would prefer to wait until it is possible to directly talk to those who sent him.

Unless Rouhani has been fielded to deceive the outside world and buy time for Tehran, he should be allowed to speak and act with authority when the next round of talks with the P5+1 group opens next week.

Amir Taheri was the executive editor-in-chief of the daily Kayhan in Iran from 1972 to 1979. He has been a columnist for Asharq Al-Awsat since 1987.