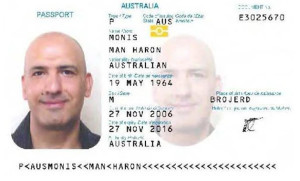

The coroner’s inquest in Australia into last December’s siege in Sydney by Iranian immigrant Man Haron Monis has now concluded two weeks of hearings focused on Monis’s strange life.

The inquest will resume in August with a focus on how Monis acquired his gun and how the police handled the siege.

The last two weeks have portrayed Monis as a very odd character, to say the least.

Monis went by more than 30 names. He would change phone numbers every two or three weeks, fearing government tracking. Some who testified knew him as an Egyptian, others as a Romanian.

In the space of a few days, he would circulate both as an austere cleric and a playboy who drank and drove fast cars. For a few months in 2013, he was biker, until the Rebels declared he was “weird” and took his motorcycle.

Tracking his various incarnations has proved easier than expected because Monis had a “curious feature of administrative compliance,” Jeremy Gormly, the senior lawyer in the inquest, said. Monis kept fastidious records, registering his name and address changes, filing tax returns. “The contrast between compliance and illegality is a thread that runs through most of his time in Australia,” Gormly said.

Impressions of Monis also clashed. A woman he dated said he lavished her with gold chains, paid for clothing, lent her one of the three cars he drove. (Each had a custom number plate: MNH001 to 003, the initials for one of his aliases, Michael Heyson.) Iranian men he knew remembered he was often broke. “Two times he asked me to send money to his mother,” one associate, Amin Khademi, said.

Why did he leave Iran for Australia in 1996? All the power and resources of the coroner’s court couldn’t find an answer. Monis claimed to have fallen foul of the authorities in the Islamic Republic after publishing a book of subversive poetry (reviews of it “ranged from mixed-quality to bad”). Iran has said he was accused of involvement in a $200,000 fraud; but that isn’t clear . There were whispers also of some unspecified “sexual misconduct.” Gormly effectively threw his hands in the air. “It’s difficult to reach any sound conclusion as to what caused Mr. Monis to leave Iran,” he said.

Monis baffled professionals. After collapsing twice in the street in 2010, he was referred to a psychiatrist, Kristen Barrett. He sat in her waiting room wearing a hat and dark sunglasses. “[He was] very evasive in his answers,” Barrett told the inquest. “He felt that he was being watched by various groups in Iran and in Australia, and that that had been ongoing for 14 years. He felt he was being watched all the time, even in the bathroom.”

She gave a provisional diagnosis of chronic schizophrenia. He was prescribed the antipsychotic drug Risperidone. Initially he improved. “[He was] less worried about being followed,” Barrett said. “Sometimes he didn’t worry about it at all.”

Unbeknownst to her, Monis was also seeing another psychiatrist at the time, telling him things he never told Barrett. Dr. Daniel Murray had treated Monis in three sessions in 2005, and twice more in 2010. In contrast to Barrett, he told the coroner he saw evidence of depression, but “no indication in terms of [Monis’s] dress, appearance, or behavior … that he had a concerning psychotic illness.” Such signs would have been “unmissable,” he said.

So what was he? Psychotic or depressed? Neither? Both?

Gormly raised another possibility, asking Murray “whether you consider, having heard that one story is going to one psychiatrist, another is going to another psychiatrist, that there is some manipulation going on there.”

“Certainly that would be a reasonable inference to make,” Murray replied.

Monis told fabulous lies. His statement to the Immigration Department in support of his bid for political asylum is riddled with them. He claimed to have been recruited by US intelligence on a business trip to Romania, liaising with a handler in Cyprus. “There he was given a name, secret code and a telephone number to the CIA,” notes of his interview said.

In January 1996, Monis claimed he was flown to Washington, DC. “There he met high-ranking CIA officials, was invited to a number of dinner parties and was taken on sightseeing tours.”

He also claimed to belong to the Ahmadi sect of Islam, making him a target of Iran’s secret police. Yet he said he became a spy for them too, while remaining a “secret follower” of the Ahmadis. “This was almost certainly a fiction he told to obtain refugee status,” Gormly said.

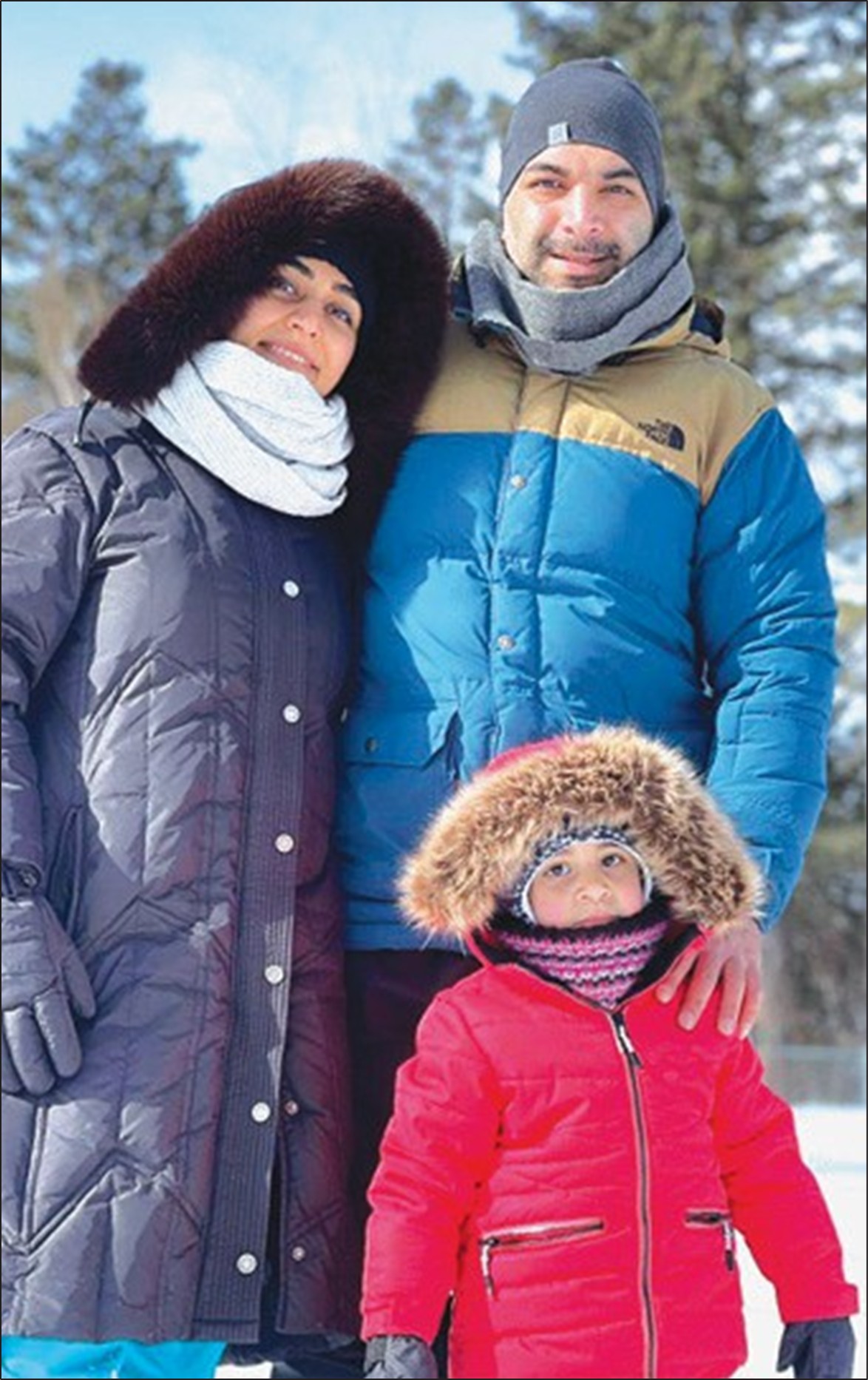

Even his partner of approximately nine years, Noleen Pal, did not know his real age. Though they had two children, most nights the couple would sleep apart, she at her family home, Monis in an apartment packed with cameras – to film, he said, the very profitable wizardry and “spiritual consulting” work he did for more than six years starting in 2002.

“Do you want to clean the evil spirit and improve your spiritual life?” said his advertisements in a Fijian-Indian newspaper published in Australia. More than 500 women did. Once they undressed, he would paint them with water, and diagnose them as suffering from curses or black magic. Touching or else full penetration would follow. Routine sexual assault was profitable work for Monis. Some years the business made more than $120,000.

A few people suspected a dark side. The family of his most recent girlfriend got the feeling “like this guy was hiding something, but we didn’t know what.” He refused to allow photos to be taken of him at family gatherings and wouldn’t even confirm if he had an Australia driver’s license. Four years ago, they reported him to the national security agency, which said he was not a concern of theirs.

None of the witnesses so far was particularly fond of Monis. Most regarded him with faint disdain. There was just one, melancholy hint of warmth in eight days – a letter from one of the daughters he left in Iran, gushing to him about her wedding. She had chosen her husband, she wrote, because “he would come with me, to you, where you are, outside of IranÖ. I want you to know that my wish is to be next to you for the rest of my life. And I promise I won’t interfere with your private life,” she wrote.

By 2014, Monis had reached the edge of his hubris. He was facing more than 40 sexual assault charges stemming from his spiritual healing business. “He had no money, no property. He was in debt,” Gormly said. “He had developed no employment skills. His attempt to develop a personal religious following … had failed. Indeed, the Islamic community in Australia did not accept him.

“He had few friends and no standing with any group or institution. His attempts to join other groups, even the bikies who tolerated him for a short period, failed…. The likelihood of a lengthy jail sentence was high. His grandiose self-assessments of the past were simply not coming to fruition.”

Weeks after Monis’s death, the Islamic State’s English-language magazine, Dabiq, gave Monis what he never attained in life. He was embraced as a great man. The article was geared to encouraging others living in the West to carry out similar attacks, bringing “mass panic” and “terror” to an “entire nation,” as Monis did. What’s more, acts like Monis’s will cleanse one’s sins. “Any allegations leveled against a person concerning their past are irrelevant as long as they hope for Allah’s mercy and sincerely repent from any previous misguidance,” it said.