July 5, 2024

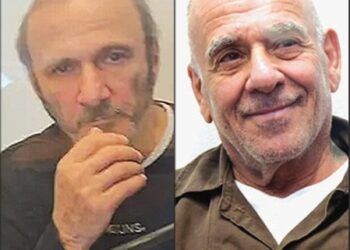

by Warren L. Nelson I n a stunning upset, Reformist candidate Masud Pezeshkian has defeated the regime-preferred candidate, Saeed Jalili, to win the presidency of the Islamic Republic in a run-off election with 55 percent of the votes. The outcome was remarkable because a huge portion of Reformist voters were boycotting the election. Just under 50 percent of eligible voters turned out at the polls for the run-off July 5, suggesting that if more had shown up, Pezeshkian’s margin could have been overwhelming. Pezeshkian, a heart surgeon by profession, won the run-off with 54.8 percent of the vote to 45.2 percent for Jalili and 2.0 percent spoiled, blank and invalid ballots, which is a low percentage.

Pezeshkian’s victory also means that the regime’s preferred candidate for the open seat of the presidency has only won once since Ali-Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani retired in 1997. In 1997, Mohammad Khatami defeated the regime-preferred candidate, as did Masud Ahmadinejad in 2005 and Hassan Rohani in 2013. Only the regime anointed Ebrahim Raisi won the office, in 2021, and that was when the regime barred all but unknown Reformists from running for the office. The July 5 result was a continuing display of public opposition to the candidates the regime has wanted to see in the office. It could also be seen as a slap-tothe-face of Supreme Leader Ali Khamenehi, who criticized Pezeshkian’s campaign positions and was clearly opposed to his election.

Pezeshkian’s victory also means that the regime’s preferred candidate for the open seat of the presidency has only won once since Ali-Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani retired in 1997. In 1997, Mohammad Khatami defeated the regime-preferred candidate, as did Masud Ahmadinejad in 2005 and Hassan Rohani in 2013. Only the regime anointed Ebrahim Raisi won the office, in 2021, and that was when the regime barred all but unknown Reformists from running for the office. The July 5 result was a continuing display of public opposition to the candidates the regime has wanted to see in the office. It could also be seen as a slap-tothe-face of Supreme Leader Ali Khamenehi, who criticized Pezeshkian’s campaign positions and was clearly opposed to his election.

However, when the results came in, Khamenehi swiftly congratulated him and accepted the results. The Pasdaran made a point of endorsing Pezeshkian as president hours after the results were announced. The vote was also a repudiation of the far, far right. Jalili was the most extreme rightist ever to contest for the office of the presidency. He campaigned as a staunch supporter of mandatory hejab and strong opponent of improved relations with the West, advocating for closer ties with China and Russia. His economic positions were vague and amounted to little more than endorsing the current economic policies.

The unanswered question is whether Pezeshkian can make even minuscule changes in national policies. He himself publicly acknowledged during the campaign that the key policy decisions lie with the Supreme Leader who has demanded mandatory hejab, strongly opposed talk of improved relations with the West, and repeatedly endorsed the economic policies of the late President Raisi. Many of those refusing to vote said they stayed home because voting was useless all it did was give the regime a veneer of respectability. The president, they said, had little power to make substantive changes, as shown by the way the revolutionary establishment neutered Presidents Khatami, Ahmadi-nejad and Rohani. Those Reformists who voted generally agreed with that view.

But they argued that while Pezeshkian wouldn’t be able to make things better, Jalili would be quite capable of making them much, much worse. The goal, they said, was not to change government policy for the better, but to stop it from becoming even more dismal. Turnout, which was a record low of 39.9 percent of the eligible voters in the first round, rose to 49.8 percent in the runoff, indicating that a considerable number of Reformist voters who boycotted the first round came out for the run-off when they saw that Pezeshkian had a chance. Pezeshkian acknowledged he could not reverse the policy of mandatory hejab, but argued that the enforcement policy must be changed so as not to punish women.

Essentially, he wants to stop enforcement. (Women who appeared at polling places without their hair covered were turned away.) On foreign policy, he might be able to open some lines to Europe but the EU has just dumped its foreign policy executor who has opposed harsh policies on Iran and replaced him with a man thought more hostile to Iran. On economic policy, Pezeshkian is likely to have a much freer hand all presidents have but if he can’t make concessions to the West to get sanctions lifted and convince the Supreme Leader to stop funding foreign terrorist groups in order to get Iran off the blacklist of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), it really won’t make much difference what policies he adopts.

In a debate exchange, Jalili said he would achieve the official goal of 8 percent annual growth in GNP “with the support of the people.” Pezeshkian viciously mocked Jalili, saying the authorities should be allowed to “execute him if he failed.” Furthermore, the new Majlis that was seated just weeks before Pezeshkian won election is comprised of at least 80 percent hardliners (see story on page 11), which will make it hard to get any liberalizing legislation enacted. The United States dismissed the election as little more than a show.

The State Department said, “The elections in Iran were not free or fair. As a result, a significant number of Iranians chose not to participate at all. We have no expectation these elections will lead to fundamental change in Iran’s direction or more respect for the human rights of its citizens. As the candidates themselves have said, Iranian policy is set by the supreme leader.” It added: “The elections will not have a significant impact on our approach to Iran, either.

Our concerns about Iran’s behavior are unchanged.” According to the official turnout figures, just a hair under 50 percent of the eligible voters came out for the run-off and a hair under 40 percent came out for the first round. In the United States, turnout in presidential elections has only fallen below 50 percent of those eligible twice since accurate records have been kept starting with the 1828 election. Those two years were 1920 and 1924, the first elections in which women could vote but many still did not think they should vote.

In the 21st Century, turnout has only fallen below 60 percent once in 2012, when Barack Obama was re-elected and 58 percent voted. The British and French parliamentary elections, held just days apart from Iran’s presidential vote, both saw turnouts of 60 percent low for Britain, high for France, much higher than recently in the Islamic Republic. Supreme Leader Ali Khamenehi has always made a major point of voter turnout, boasting that the turnout in Iran shows that the public supports the Islamic Republic.

He has ridiculed foreign governments when the turnout for their elections has been low. For example, in 2001, Khamenehi said in a sermon that a turnout of just 40 percent was a cause for shame and proved that the citizens of such countries which he said included the United States did not trust their political system. A video of that sermon has been posted repeatedly on social media in Iran in recent weeks. Reformists were deeply divided over whether to boycott the vote.

The record low turnout in the first round, suggested most Reformists did boycott the vote but the fact that Pezeshkian came in first that day raised many questions. For example, did many regime supporters skip voting on the premise that the president doesn’t matter? (The combined votes of Jalili and conservative Mohammad-Baqer Qalibaf in the first round came to 12.8 million, far below the nearly 18 million votes that Raisi got in 2021.) The fact that the turnout rose by 10 percentage points between the first and second rounds suggested that many Reformists changed their minds about boycotting when they saw the Reformist candidate actually had a chance of winning.

The issue of boycotting divided critics of the ruling elite. Former President Khatami, who publicly backed a boycott in the spring’s Majlis elections, urged the public to vote in the presidential elections. But Nobel laureates Shirin Ebadi and Narges Mohammadi both backed the boycott of the presidential vote and Crown Prince Reza also backed the boycott. So did Mir Hossain Musavi, one of the losing Reformist candidates in the 2009 presidential election. But Mehdi Karoubi, the other losing Reformist in 2009, voted this year and urged others to do so.