November 01, 2019

The Trump visa ban has blocked most Iranians who wish to visit the United States from ever getting on a flight to the US. But there are some waivers—and there may now be more.

Altogether, the Administration has granted 7,600 waivers to Iranians and nationals of the six other Muslim-majority countries impacted by the visa ban. But roughly half of those waivers were issued in just two months this summer, according to testimony to the House of Representatives by Edward Ramotowski, the deputy assistant secretary of state for visa services.

The Supreme Court overruled lower courts and allowed the visa ban to go through, in part because it included a waiver system that would allow humanitarian exceptions to the ban.

Ramotowski said the recent surge in waivers resulted from a shift to an automated processing system for visa applications.

Here is the story of a woman who received a waiver and was reunited in October with her daughter, 39-year-old Damineh Oveisi, at the Tampa Airport, as reported by the Tampa Bay Times.

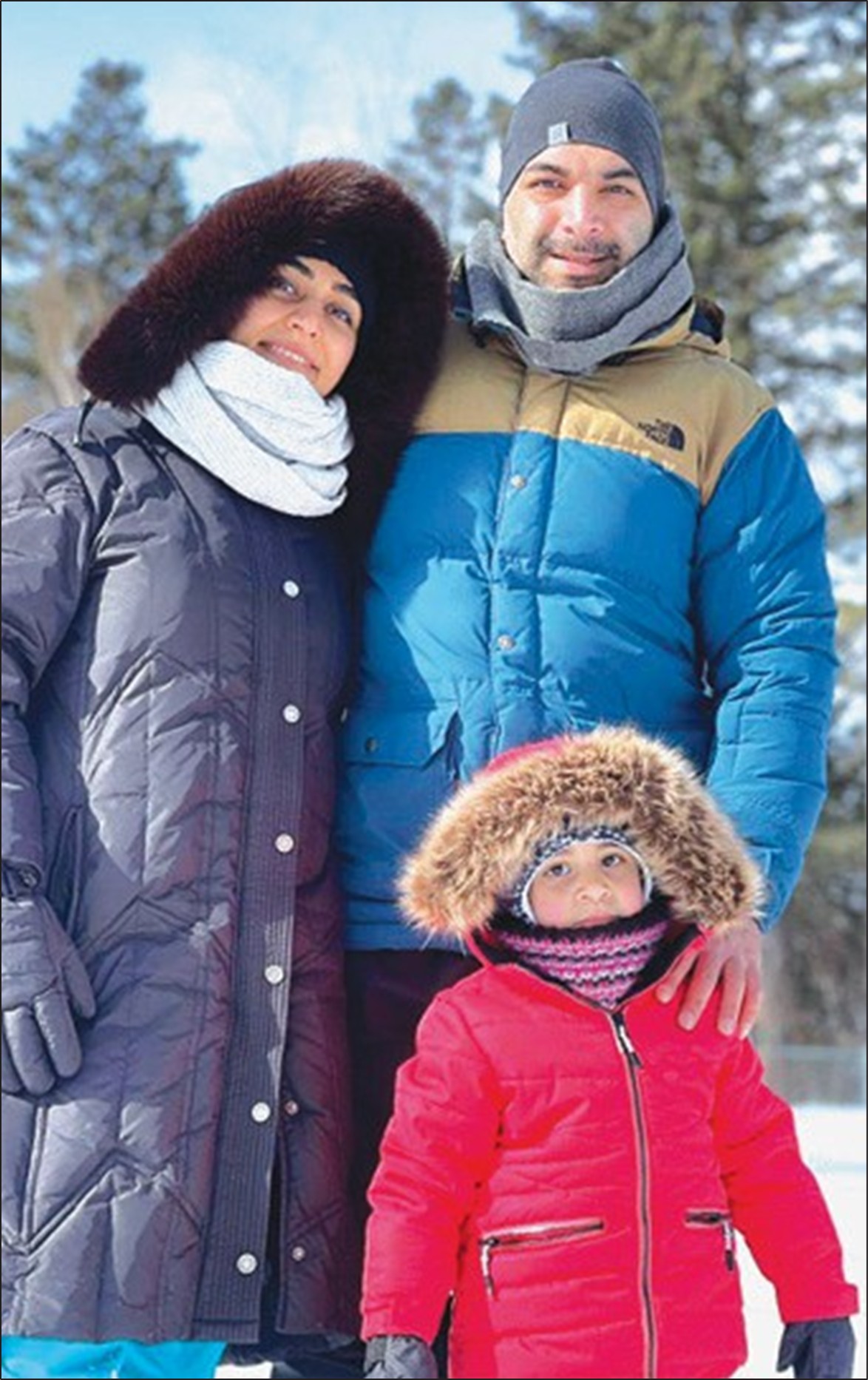

Oveisi, a US citizen born in Iran, wanted her parents, Mar-yam Rastkhiz and Lotfollah Oveisi, to see the life she had built for herself in Florida, where she works as a lab technician, owns a home and is raising an Iranian-American daughter, Leyana, 11.

Oveisi was moved to action, however, when she learned her mother had leukemia and needed a treatment that she was told wasn’t available in Iran.

Oveisi made a last-ditch effort to bring her parents to the United States in March, arguing that her mother’s medical emergency qualified for a waiver to the visa ban. She spent the next four months exchanging emails with US officials, worrying and waiting.

Approval finally came in August. It took several additional weeks to arrange the flights and for her mother to be strong enough to travel.

Oveisi spent the last week preparing her house for her parents, setting up a room downstairs so her mother wouldn’t have to climb stairs and making it cleaner than she ever remembered it.

They were at the airport as her parents’ plane arrived. But where were her parents? They must be held up at customs, Oveisi thought. She hoped the process would be smooth.

Oveisi had a moment of panic. Her mother didn’t speak any English. Her father knew a little more, but Oveisi had warned him not to say anything unless he truly understood what was being asked. She wondered if that was bad advice. What if he said nothing? What if the airport didn’t have Farsi translator?

Oveisi took a seat beside her daughter. Her phone pinged with messages from her sister in Tehran, anxious for updates.

At 7:50 p.m., Oveisi’s cell phone rang. It was a US customs official. The caller wanted to know if Oveisi was waiting for someone.

Yes, she replied. Her parents.

The caller asked for her address. Oveisi recited it quickly.

“Can you tell me, is my mother okay?” she asked.

She’s fine, the caller said. She was sitting in a wheelchair and would be on her way soon.

There had been no problems, just a minor backlog.

Young Leyana spotted them first. She leapt up from the seat and bolted toward the passengers exiting the trolley, forgetting her poster and balloons, and threw her arms around her grandmother. Oveisi scuttled behind, kissing her father then her mother.

Months ago, Leyana had it all planned out. As soon as her grandmother arrived, she would take her to see her bedroom. Then, they would paint their nails and listen to Persian music, because her grandmother would translate the lyrics better than her parents could.

But now Leyana wasn’t sure what she wanted to do first. Make slime?

Oveisi had plans of her own. She would take her mother to be evaluated by a hematologist. They would see about treatment next.

For now, Oveisi felt grateful to be able to hug and kiss her parents.

They could figure out the rest, together.