July 11, 2014

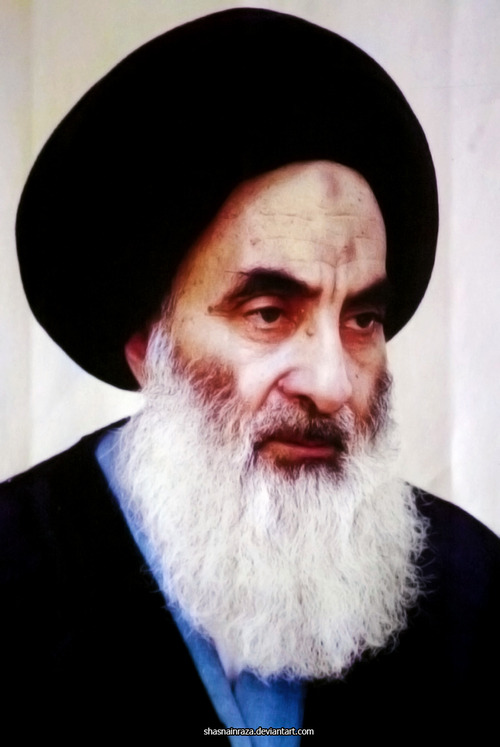

Grand Ayatollah Ali Sistani, the seniormost Shiite cleric in Iraq—and some say in the world—is now intervening in politics in ways he has long avoided and even condemned in the past.

For three straight Friday sermons, Sistani has spoken out about Iraq’s broken political system and pushed politely but firmly for changes, diplomatically suggesting that it is time for Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki to go and urging Iraqi Shiite politicians to work closely with Sunni and Kurdish politicians.

Sistani, as his name indicates, was born in Iran but has spent his adult life in Iraq. He holds almost mythological stature to millions of followers in Iraq and beyond. He is unchallenged as the senior Shiite cleric in Iraq and recognized by many as the senior Shiite cleric in the world—though that is certainly not accepted by the establishment clerics of the Islamic Republic.

Sistani has always rejected Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini’s political arguments for clerical rule. Until now, he has made few political comments beyond urging Iraqi Shias to vote and Shiite politicians to rule with the tenets of Shiism in mind.

But this past month, that has changed. Sistani has insisted that Shiite politicians choose a new government without delay—an order widely seen as geared to hastening the end of Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki’s eight-year tenure.

Sistani has not, however, issued any direct commands endorsing or rejecting any potential candidates. And he has not adopted the Khomeini dictum for clerical rule, though he is trying to throw his weight around more than in the past.

The cleric kicked off his newly assertive stance June 13 with a fatva for Iraqis to take up arms against the group that now calls itself the Islamic State. The last time the Najaf clerical leadership issued such a call was in the 1920s when the British took over Iraq. Sistani pointedly refused to issue any such call to oppose the US invasion of 2003 and subsequent occupation of Iraq.

Tens of thousands of men have heeded his call to arms, bolstering an army that has seen about a quarter of its combat units simply dissolve.

Next, Sistani appealed for an inclusive government of all Iraqis, a call widely seen as an implicit rebuke of Maliki—even by some of the premier’s supporters.

Lastly, Sistani called on the political blocs to choose a prime minister, president and speaker of parliament by July 1, a deadline that was not met, which points to clear limits on Sistani’s influence.

Sistani, who speaks Arabic with a distinct Persian accent, does not deliver his sermons himself. They are read by an aide.

The three fatvas carry risks. Sunni leaders say Sistani’s call to arms inflamed the conflict. More broadly, the fatvas revive the old question of what role Najaf’s clerics should play in affairs of state.

“He gave a fatva the Shiites never had for 90 years or more. He will not retreat. He wants to have a role,” a Western diplomat with strong knowledge of the clerical establishment told the Reuters news agency, referring to the call to arms. “It would be seen as irresponsible for him to pull back after issuing such a fatva.”

Sistani is chancellor of the thousand-year-old Najaf seminary, the most senior of its four grand ayatollahs, and the most widely emulated in Iraq. To the millions who follow him, his Islamic legal opinions, or fatvas, are beyond question.

Mohammad Hussein al-Hakim, whose father is another of Najaf’s four top clerics, reaches deep into history to describe the threat Shiites now feel from the hardline Sunni Islamists spearheading the insurgency.

Two centuries ago, in 1806, puritanical Sunnis rampaged through the holy city of Karbala north of Najaf. Without the clerics’ intervention, Hakim said, history might have repeated itself.

“Now the capabilities are bigger, the destructive forces are stronger, and the destructive ideas are greater,” he said at the offices of a charity for orphans financed by his father.

He listed abuses and atrocities committed by the Islamic State group: tombs have been razed, Shiites murdered, mosques sacked. “They will leave no culture or values behind,” Hakim said. “Their behavior is monstrous.”

During interviews with Reuters, clerics also invoked the 7th century assassination of Imam Ali.

The greatest risk of Sistani’s activism, Sunni critics say, is that it may sharpen the sectarian edge of the conflict.

“Sistani now is ordering them to wear fatigues and fight Sunnis,” Sunni cleric Ahmed al-Kubaisi told Saudi Arabia-owned Al-Arabiya television last week.

Rifa al-Rifaie, a senior Sunni cleric, condemned the fatva, comparing it mockingly to Sistani’s earlier restraint. “Sistani, that lion, where was he when the Americans occupied Iraq?” he asked. “We have been treated unjustly, we have been attacked, our blood has been shed and our women have been raped.”

Supporters say Sistani’s call to arms was carefully phrased to call on all Iraqis, not just Shiites, and that it is the Islamic State that wants to make this an issue of sect.

Others argued the fatva actually reduced the chance of a bloodbath by encouraging people to fight only within the state-guided armed forces, rather than take matters in their own hands.