January 17-2014

. . . boasts mightily

by Warren L. Nelson

President Rohani is boasting that the great powers of the world all “surrendered” to Iran in signing onto the interim nuclear agreement, which will go into effect Monday for six months.

The exaggerated boasting was undoubtedly intended to counter hardliners in Iran who say Iran got nothing from the agreement. But such boasting threatens to undermine support in the West where such talk contradicts the image of Rohani as a peacemaker.

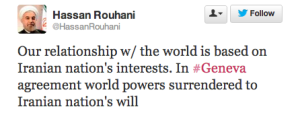

Rohani spoke of the major powers “surrendering” to Iran in repeated speeches this week. In case there was any argument over the translation, Rohani sent out a tweet Tuesday in English that said: “Our relationship w/ the world is based on Iranian nation’s interests. In #Geneva agreement world powers surrendered to Iranian nation’s will.”

The agreement is drawing an astounding volume of news coverage and is being treated all around the world as an immense development. But the reality is something considerably less. The agreement is important as the first positive development in the nuclear issue in a decade. But if there is a permanent agreement reached in six months, this interim agreement will soon be a mere footnote in history. And if no permanent agreement is reached, and the clash with Iran escalates, the interim agreement will still likely go down in history as a footnote.

The interim agreement was signed November 24. But it took three sessions by technical staff to work out the details. Those were completed Friday night and sent to the seven concerned capitals where the political leaderships all signed off by Sunday.

In an interview with the Iranian Students News Agency (ISNA) Monday, Iranian Deputy Foreign Minister Abbas Araqchi disclosed that there was a 30-page “secret” appendix governing the interim agreement. That swiftly raised suspicions in Congress that Obama had granted Iran more concessions and was trying to hide them.

Araqchi referred to the document as a “nonpaper,” using the English word. “Nonpaper” is used in diplomacy to refer to a document the drafters do not wish to acknowledge or have attributed to them. It is a document normally used to help discussions without committing anyone to anything. It was a very bad choice of words for an Iranian diplomat to use when the Obama Administration is desperately trying to convince Congress the interim agreement is a good idea.

The words “surrender” and “nonpaper” can only make it harder to sell the idea of dealing with Iran to the American pubic.

White House press secretary Jay Carney said the text of the technical agreement would be submitted to Congress and he denied there was any secret annex. A State Department official briefing reporters Monday said the EU, as the leader of the talks, and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), to whom much if not most of the documentation is addressed, will decide what to make public.

As for Rohani’s contention that the Big Six powers—China, Russia, Germany, France, Britain and the United States—had all collectively “surrendered” to Iran, Carney brushed that aside as mere political rhetoric meant to make the agreement more appealing inside Iran.

“It doesn’t matter what they say,” Carney commented. “It matters what they do.”

He told reporters, “It’s not surprising to us—nor should it be to you—that the Iranians are describing the agreement in a certain way for their domestic audience.”

Araqchi said the nonpaper deals with such matters as Iran’s right to continue research and development (R&D) work on centrifuges and how the Joint Commission overseeing the agreement will operate.

The suggestion that rules on centrifuge R&D would be hidden in a nonpaper is not likely to go over well with Congress.

Araqchi also said the Joint Commission would have the authority to resolve disputes. But US officials previously said the commission was a forum for discussion and not for arbitrating disputes. The suggestion by Araqchi that a secret document contradicts what US officials have said publicly could enrage many in Congress.

Before the Iran Times went to press, Araqchi had not reacted to the growing furor he set off.

News reports earlier said the issue of centrifuge R&D had been a major topic of the technical talks. US officials indicated Iran would not be allowed to actually build any new test centrifuges. It would be able to continue to operate the half-dozen different kinds of centrifuges it has already built and runs in a test center at Natanz. It would presumably be able to modify them, but not to build entire new centrifuges. A major part of the agreement signed in November says Iran can build no new centrifuges for the duration of the six-month agreement.

The IAEA has called an extraordinary meeting of its 35-nation Board of Governors for January 24 to take up the agreement. The IAEA has been tasked to conduct all the inspections required to show if Iran is fulfilling its obligations under the agreement. The IAEA has estimated it will need an extra $6.8 million to carry out the additional workload, and that will be a major topic of the meeting.

The agreement takes effect January 20 and Iran is to halt all enrichment beyond 5 percent as of that date. It is also to immediately dismantle the linkages among centrifuges that have allowed it to enrich to 20 percent until now. IAEA inspectors were due to arrive in Tehran January 18 to verify that Iran has complied with that part of the agreement.

The EU and US will lift the few sanctions the agreement ends as of January 20. The EU foreign ministers will hold their monthly gathering that day and are expected to adopt the agreement then. All the EU’s parts will take effect immediately. They mainly involve the lifting of some restrictions on insurance and re-insurance. But companies in that business said they don’t expect any practical changes right away because the restrictions on banking transactions essential to the insurance business will remain in force. Furthermore, Iran’s National Iranian Tanker Co. (NITC) will remain under sanctions, barring the insurance firms from doing business with NITC.

Two parts of the agreement, however, will be staggered over the life of the six-month accord—cash payments to Iran of funds frozen by US sanctions and the dilution of half the 20 percent enriched uranium in Iran’s hands.

The agreement calls for Iran to dilute half of the 20 percent enriched uranium it has stockpiled so that the uranium is enriched to less than five percent. Araqchi said that dilution would take place in six one-month stages and be verified by the IAEA.

The agreement also calls for Washington to allow Iran to receive $4.2 billion of more than $50 billion in Iranian funds that are currently locked up in foreign banks. Many critics in the United States complained that Iran would get its hands on all that money and could then just forget about its obligations under the agreement. The US, therefore, made a major point of spacing the payments over the full length of the agreement.

The payment schedule gives Iran $1 billion in March and another $1 billion in April with payments of $550 million in February, May, June and July—with the final payment coming on the final day of the six-month agreement. Here is the payment schedule an unnamed US official provided to Reuters:

Feb. 1—$550 million

March 1—$450 million

March 7—$550 million

April 10—$550 million

April 15—$450 million

May 14—$550 million

June 17—$550 million

July 20—$550 million

The dilution of Iran’s uranium and the payments to Iran are not actually parallel. If the agreement falls apart, Iran can re-enrich the diluted uranium back to 20 percent, but the United States will not be able to re-freeze the $4.2 billion in payments.

But the total payments come to only $4.2 billion. That is not even 10 percent of the more than $50 billion the United States says is frozen in accounts around the world. Furthermore, at current rates, Iran will earn more than $18 billion in oil sales over the next six months and most of that will go into blocked accounts, so Iran will actually end up with more frozen funds at the end of the six-month period. What’s more, the unfrozen funds can only be used by Iran to import goods that are not sanctioned. That list will grow Monday to include automotive parts, gold and other precious metals—not exactly a massive list.

In addition, the State Department has said Iran will earn about $2.5 billion from sales of petrochemicals and other items, from which sanctions are now being lifted. No one has said how that figure was calculated. And it isn’t clear how Iran will market its petrochemicals with banking restrictions still in place.

More important than the six-month interim agreement is what happens next. Will the seven countries succeed in reaching an agreement to govern Iran’s nuclear program far into the future beyond six months?

Foreign Minister Zarif said Monday that he thinks it will be easy to reach a long-term agreement.

Secretary of State Kerry said Sunday that the next stage of the talks would be “very difficult.” President Obama last month said he saw the chances of success at less than 50-50.

No date has been set for the first meeting on the long-term agreement, but those talks are expected to start in February.