December 23, 2016

The rial has fallen in value against the dollar by about 8 percent since the US election last month—but many other currencies have suffered a similar dip.

The rial has fallen in value against the dollar by about 8 percent since the US election last month—but many other currencies have suffered a similar dip.

The rial is suffering. It passed 39,000 to the dollar last Wednesday and has remained above that mark since. But the fact is that all major currencies have lost value against the dollar as the dollar has strengthened markedly.

The tendency in Iran has been t o look at the rial’s slippage as a result of President Rohani’s policies and/or the inability of Iran to draw foreign investment since the end of sanctions.

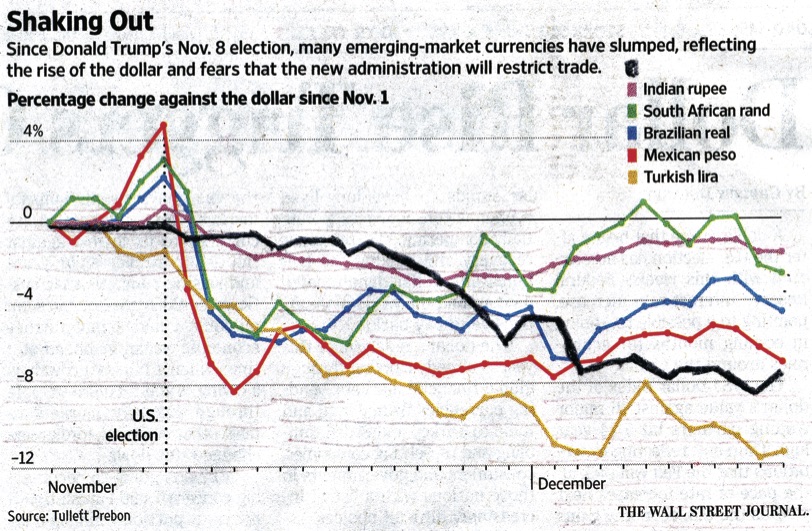

But the accompanying chart suggests Iran’s rial may just be suffering the same post-US election doubts that have hit many other currencies in the developing world.

The accompanying chart was prepared by The Wall Street Journal to show the post-election slump in the currencies of India, South Africa, Brazil, Mexico and Turkey. The Iran Times has added the rial.

The other five currencies all began to slump in the first few days after the election. The value of the Iranian rial against the dollar slipped too, but only marginally. It wasn’t until November 25 that the rial caught up with the other five currencies—and in the next week passed all of them except the Turkish lira in a downward rush.

The Iranian rial is now down about 8 percent compared to the dollar, while the Turkish lira is down almost 12 percent. The other four currencies appear to have stopped falling and even recovered a bit.

The chart ends with the close of Western markets Friday and Iran’s currency market Sunday.

Much of the change shown in the chart reflects the strengthening of the dollar rather than a weakening of other currencies as the market reflects a belief that the American economy will grow under President Donald Trump. The same faith has been shown in a large jump in the US stock markets since the election.

The Wall Street Journal’s Dollar Index showing the dollar’s value against 16 major US trading partners hit a 14-year high last Thursday, though it should be noted that the index has been rising generally ever since bottoming out in 2011.

A strong dollar makes it more expensive for countries with dollar-denominated debt to make their debt payments. That is true for most countries. But Iran has little debt at all and little (if any) of that is dollar denominated. So Iran will be hit less in that regard than most other countries.

The main impact on Iran is the psychological blow of the decline in the value of the rial vis-a-vis the dollar. But Iranians probably ought not to blame the Islamic Republic for a slippage that is hitting almost all currencies—not just in the developing world.

Since the election, the euro has fallen from $1.10 to $1.04. The yen has lost more than 12 percent against the dollar, half again as bad a hit as the rial has taken. In China, there is great fear for the fate of the yuan, which has fallen to its lowest against the dollar in more than eight years.