November 27, 2020

The government has from the beginning resisted tough restrictions for fear of a public uprising. It is clear the regime leadership is extremely fearful of a new revolution that would topple the regime and does not want to prompt an uprising by using its powers to impose a total lockdown.

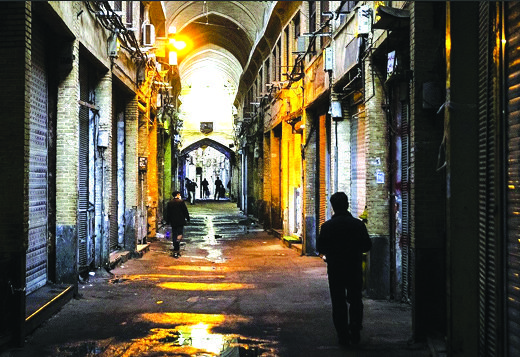

government restrictions. And the streets of Tehran (below) were deserted after

the 9 p.m. curfew. But many said other coronavirus restrictions were largely

being ignored by the public.

The closest thing to a total lockdown was imposed November 21, however. The regime says the public is complying, but many others say the public is largely ignoring the regime rather than rising up in rebellion.

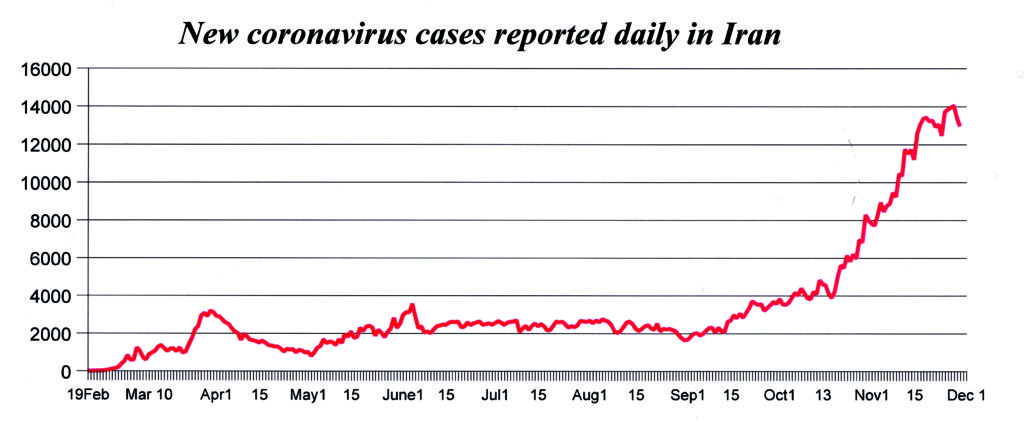

The government has been trying to figure out how to respond to the surging number of new cases of the disease. The daily numbers of new cases ran from 2,000 to 3,000 in the first surge in the two weeks after Now Ruz. But the numbers then dropped below 2,000 and, on a few days, below 1,000, leading the public to grumble about restrictions.

The numbers bounced around with a new surge starting in October and the daily count passing 4,000 on October 6, 5,000 on October 20, 6,000 on October 23, 7,000 on October 27 and 8,000 October 29.

November saw record daily tolls set on 12 days, with the latest record of 14,051 set on November 26, five days after the newest, near-lockdown restrictions went into effect.

The death toll has also risen, but not as dramatically as the caseload. The death toll was in the 400s every day but one in November, although it only topped 400 on one day prior to November 1.

Statistics on available hospital beds are not released by the government, but anecdotal reports from scattered hospitals all around the country speak of hospitals running out of beds and ventilators for coronavirus patients, and of patients being brought to emergency rooms and told to go somewhere else.

On November 4, Dr. Farshad Allameh, president of the Tehran University of Medical Sciences, said Tehran had run out of beds allocated for coronavirus patients. However, one week earlier Health Minister Saeed Namaki said, “We should not cause panic for people in vain. We should never announce that we don’t have empty [hospital] beds. We do have empty beds.”

Five days into the tightened restrictions, President Rohani lauded the public and said, “On average, 90 percent of the people are following health guidelines.”

But, on the very same day, Dr. Alireza Zali, chairman of the Tehran Coronavirus Task Force, said there had been no significant change in the scale of hospitalizations in Tehran. He also complained that 151 people confirmed with the coronavirus had flown from Tehran to other provinces on November 24 alone.

But Transport Minister Mohammad Eslami said airline, bus and rail officials had checked the list of those confirmed with coronavirus and stopped 700 from boarding intercity transportation.

And on the day that tougher restrictions on government employees went into effect, November 28, the Health Ministry said things were going so well that 89 of the 160 cities on the red or high risk list had been removed

The government has clearly been divided over what to do, with health professionals generally calling for a total lockdown, while economic officials argue against that for fear of causing a collapse in the economy, and security officials opposing too harsh a lockdown for fear of prompting an uprising. In early November, the Tehran City Council voted to ask the government for a total lockdown in the capital.

Supreme Leader Ali Khamenehi took cognizance of the rising threat from the coronavirus October 24, when he demanded for the first time that the government prioritize public health considerations over “the security and economic aspects” of the pandemic. But it isn’t clear that has had much effect. Regime officials are often very selective in deciding which orders from the Supreme Leader to adopt and which to ignore.

The confusion was evident in the government’s inability to announce the new measures being imposed when they said on November 15 that new measures would take effect November 21. The full range was not announced until November 21.

The restrictions apply in 448 cities and towns accounting for 80 percent of the population. The most stringent rules applied in 160 “red” cities, including Tehran, where the coronavirus was raging the most.

The new rules apply for two weeks, but can be renewed if needed. Many thought the two-week application was announced just to make the rules more palatable and that the clandestine plan was to extend them. All businesses have been ordered to close accept “essential” businesses, defined as food shops, bakeries, pharmacies, car repair shops, chain stores, print shops, physicians’ offices and hospitals. The government didn’t explain why print shops and car repair businesses were essential. The Tehran Guilds Chamber said the businesses allowed to remain open account for 30 percent of all businesses in Tehran.

Only one-third of civil servants were to come to their offices to work on any individual day, except for essential services such as water, electricity, gas and health services. Only one-half of the staff involved in public transport, postal services, banking and other services was to work on any given day.

A week later, the government changed that and said all government offices would effectively close with only essential employees going to work. It said managers would decide who was essential, but did not give them guidelines.

On the morning of November 21, when the restrictions took effect, the streets of Tehran appeared as busy as usual. And many shops that were supposed to be closed were wide open. Many offices were clearly ignoring the orders as most staff were visible at their desks. What proportion was in offices and what proportion was at home could not be determined,

One woman who works for an import company said she had trouble finding a parking space when she went to work November 21. She insisted that the government rules did not apply to the private sector, which was not true.

The Tehran Bazaar, which is all private sector, was locked up tight. That is an easier place to impose the rules because of its limited number of entry points.

The director of a cosmetics firm said the lockdown “affects mostly street vendors and businessmen who are right in front of the authorities’ eyes and must lower their shutters. But we in private companies are often operating behind closed doors.”

The new rules are also aimed at halting long distance travel. Cars found with out-of-city license plate are to be ticketed. There was talk about police barricades on major highways to stop people from traveling outside their home city.

Even within cities, cars are forbidden to be on the roads between 9 p.m. and 4 a.m. No one explained how that would contribute to halting the spread of the disease. But it was the one restriction that was easily enforced and clearly being enforced.

Health Minister Namaki said the new restrictions were “the last chance for the health system to stop the virus.” If the new rules are ignored, he said that “means we will be in an abyss that we can no longer recover from…. We are facing a virus bomb, and the spreading power of the virus has increased ten-fold.”

The Coronavirus Task Force said violators would be fined. The fine for intercity travel would be 10 million rials ($40) for each 24 hours a car was found in a red city.

A poll taken in late October of 1,297 Iranians all over Iran found that 55 percent of the population have some level of trust in the government’s ability to cope with the coronavirus while 39 percent do not; 25 percent, have no trust whatsoever in the regime’s measures to stop the epidemic.

But the poll also showed the public as supporting tougher measures than had been introduced by October. For example, 72 percent supported a national quarantine. That contradicted the supposed concerns in security agencies of prompting an uprising.

Another concern came from Deputy Health Minister Iraj Harirchi, who said that 20 percent of the people who tested positive for coronavirus have refused to quarantine themselves.

The most prominent Iranians known to have contracted the disease are former Prime Minister Mir-Hossain Musavi, 79, and his wife, Zahra Rahnavard. And the irony is that they are quarantined—being under house arrest since 2011. Still, they are not totally isolated as they have been allowed in recent years to receive visits from their children and some friends. They were reported with the coronavirus November 15, the same day the government announced the lockdown to begin November 21.

A teacher who came down with the coronavirus in Garmeh, Khorasan North province, insisted on teaching her classes via video. A photo showed Maryam Arbabi, a teacher for 22 years, lying in a hospital bed linked up to hospital gear and lecturing from a book. A few days later, she died.

Meanwhile, the Legal Medicine Organization announced that traffic deaths in the first six months of the year (March 20-September 21) were down 16 percent. That is the one trustworthy measure of the impact of travel restrictions and suggests that the public has reduced its travel, albeit not hugely. One limitation with this statistic is that it includes traffic deaths in cities, where the disease would not reduce travel much, as well as from inter-city highways, where the government has sought to reduce travel substantially. Road traffic has undoubtedly increased in Tehran as people are trying to avoid buses and subway cars. The Tehran City Council said the public transportation system in the capital had 5 million passengers a day before the pandemic, but now has only 1 million.

Oil Minister Bijan Namdar-Zanganeh said that US sanctions have deprived the country of needed revenues and complicated the response to the coronavirus. Because of that, he said, the United States is responsible for every death from the disease in Iran. The Red Crescent Society, however, said there is no shortage whatsoever of medicines used by coronavirus patients.

Djavad Salehi-Isfahani, professor of economics at Virginia Tech University, says a statistical analysis suggests the government is only reporting about 40 percent of the coronavirus deaths in the country. That would mean the true death toll is about 2-1/2 times the reported number, which was approaching 50,000 at the end of November.

He compared the reported coronavirus death toll in the spring and summer months of this year with the death tolls from all causes reported by the state agency that tracks births and deaths for this spring and summer and the same six-month periods in the preceding seven years. The result he said is that the government agency reported 55,834 more deaths over those six months this year than the average of the previous seven years. But the government reported coronavirus deaths totaling 22,834 in that time period, leaving 32,475 “excess deaths” this year. With no explanation for those “excess deaths,” the most likely cause is the coronavirus.