December 21, 2018

The government has been desperately trying and so far succeeding—in pushing down the price of the US dollar on the open market.

As of the last trading day before the Iran Times went to press, the Central Bank reported the open market rate was down almost to 100,000 rials to the dollar. Government officials have been quoted as saying they think the price should go down to somewhere between 80,000 and 90,000 rials.

There are suspicions as to whether some finagling is going on. An Iranian journalist, writing in the American Foreign Policy magazine says that the collapse of the rial, which saw the price surge (for one day) to 190,000 per dollar, was actually caused by manipulators trying to make a profit and did not reflect economic facts. More on that later in this article.

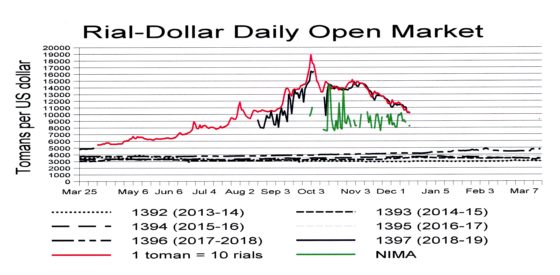

The price of the dollar was 149,000 rials on November 4, the last day before the Trump Administration re-imposed oil sanctions. One would expect the rial to slide at that point. But, instead, it has steadily improved and was selling for 102,603 rials on December 13.

These are the prices posted by Sanarate, which has been taken over by the Central Bank of Iran. Other websites posted slightly different figures for December 13—107,500 on Bonbast, 99,910 rials on Mesghal, and 101,300 on 2gheroon. But all have been heading downward since November 4, when all were above 140,000.

Whether the price will get down to 80,000 to 90,000 rials per dollar—and stay there—remains to be seen.

On NIMA, the story is somewhat different. NIMA is the official market where exporters are supposed to sell their foreign exchange earnings to importers. The open market, the shops that line the streets, is for citizens who need smaller sums for travel abroad or to support students abroad.

The Central Bank began posting the selling prices on NIMA as of September 26. The most noticeable thing about the NIMA sales is how erratic they are—even more erratic than the open market sales. Even more curious is that NIMA has recorded no dollar sales at all on 11 of the 63 market days since the Central Bank began posting figures! That suggests that NIMA is not the big market it is supposed to be.

Some wildly erratic daily sales figures suggest the same thing. For example, for October 22, NIMA posted the average selling price of the dollar at 77,368 rials. The next day the average price was 139,125, a jump of 80 percent, which is not rational. The following day the price was 87,688, a plunge of 37 percent. This suggests a paucity of sales allowing for such irregularity.

The government admits it is still trying to get exporters to obey the rules and sell their dollars on NIMA. The government conceded that it is still short of all the foreign exchange it needs when on December 8 it announced that money exchange offices are now free for the first time in decades to import foreign banknotes. But if Iran is short of the volume of foreign currency it needs, then the open market prices should not have been improving for the last month and a half.

What is moving the market now is anything but transparent. Similarly there is no transparency about what caused the sudden, albeit brief surge, from 150,000 rials to 190,000 rials back in September.

In a recent issue, Foreign Policy magazine said, “It isn’t just US sanctions and the fundamental weaknesses of the Iranian economy that have contributed to Iran’s currency freefall. It’s also the deliberate circulation of rumors and fake news on Telegram by Iranian currency traders and middlemen out to make a profit.”

Rohollah Faghihi, an Iranian journalist, writes, “As soon as it became clear that the United States would reimpose sanctions, many middle-class and wealthy Iranians felt a temptation to engage in currency trading, having concluded that the value of the rial would soon decline. For all these Iranians, the goal was to buy dollars. Some Iranians even sold their homes and invested the proceeds in dollars to preserve the value of their assets—or, simply, to secure a profit.”

That has long been known. In fact, the rapid sell-off of rials weakened the rial even further, and the Iranian government tried to arrest it in various ways, including by banning the official sale of foreign currency. But this only served to make the currency-trading market less transparent—and, correspondingly, more easily exploited.

Faghihi wrote, “There has always been a gap between the more sophisticated currency traders and those driven by ignorance and fear, but the informal marketplace widened it. That has become especially evident on Tehran’s Ferdowsi Boulevard, the center of Iran’s informal money-changing economy, where anyone can bring rials in cash and walk away with US bills.”

He said, “In one instance on Ferdowsi, I recall seeing one elderly women bring the equivalent of her entirely yearly income and exchange it at a rate of 170,000 rials to the dollar—an offer significantly below what the rial was then worth, even as the consensus was that the currency was probably undervalued at that moment. The rial has yet to weaken to the point that the woman’s bet would have paid off.”

Faghihi explained, “Iran’s professional money traders increasingly use Telegram to exploit the black market’s lack of transparency to maximize their own profits, at the expense of their Iranian clients—and to the distress of the Iranian government. As one of the few social media or messaging apps that the Iranian government doesn’t censor, Telegram—specifically, the news feeds on its “channel” function, which allow posts to be distributed to anyone who chooses to sign up for them—has become one of the most trusted sources of news for Iranians, displacing state media and even ostensibly independent newspapers.”

As the rial collapse grew in speed and intensity after Now Ruz, currency traders began creating hundreds of channels on Telegram, Faghihi writes, instantly announcing any shifts in the dollar price. Iranians have joined these channels in large numbers—some feeds have more than 2 million members. As a result, Faghihi argues, “They have themselves become a force capable of influencing the currency exchange rate.”

He also says: “The currency traders who run these information outposts are increasingly using them to distribute distorted economic news. For example, in recent weeks, as the rial began to regain value [since September 26], the currency-trading Telegram channels resisted the positive news. Some simply delayed reporting the rising prices; others even announced entirely false prices. Many of the channels also ignored the positive trends in favor of promoting negative analyses about the negative effects of US oil sanctions on Iranian currency.”

Iran’s authorized news media, on the other hand, carried positive news about the rial strengthening. Sometimes, they even explicitly called out the false reports on Telegram. But, Faghihi says, many ordinary Iranians have been unsure how to respond to the contradictory news reports and have held on to the dollars they previously bought rather than sell them for rials, as the most recent data suggested they ought to.

Faghihi reports that new Telegram channels have now emerged that seem designed specifically to push back against the popular channels created by the currency traders. One of the new channels is called “Dollar-Rial” and seems to have the explicit goal of supporting a strong rial while attacking currency middlemen as traitors and meddling foreigners. This channel has also succeeded in attracting over 2 million members, which Faghihi thinks suggests Iranian society might be exasperated with the manipulation of the currency market by self-interested actors. (The channel was recently blocked for unknown reasons, after which its creators launched a new channel that now has 55,000 members.)