August 16, 2024

by Warren L. Nelson

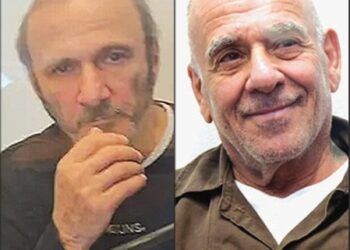

President Masud Pezeshkian has been straining the patience of Reformers by aligning himself ever closer to the Supreme Leader, bending over backward to laud the Leader, to pledge allegiance to him and to proclaim over and over again that as president he will carry out the orders handed him by the Supreme Leader. This is disillusioning to many citizens who voted for Pezeshkian in hopes that he would change many of the policies propounded by Ali Khamenehi.

President Masud Pezeshkian has been straining the patience of Reformers by aligning himself ever closer to the Supreme Leader, bending over backward to laud the Leader, to pledge allegiance to him and to proclaim over and over again that as president he will carry out the orders handed him by the Supreme Leader. This is disillusioning to many citizens who voted for Pezeshkian in hopes that he would change many of the policies propounded by Ali Khamenehi.

But others suspect Pezeshkian is trying to reassure the Supreme Leader of his loyalty so he can more effectively lobby the man to make changes. Pezeshkian has publicly and repeatedly signed on to the policy of mandatory hejab, a policy that is known to disgust him. But Khamenehi has publicly and repeatedly insisted that the dress code must be enforced.

What remains unclear is whether Khamenehi personally feels strongly about the dress code or is just reflecting what the body of clerics he cannot ignore feels about the matter. Khamenehi appears to have shifted on nuclear policy and supports Pezeshkian’s desire to negotiate a return to the Joint Comprehensive Policy of Action (JCPOA), as the nuclear agreement is weirdly named.

But the nuclear issue is not so sensitive with the clergy as is the dress code and the question of women attending soccer games. The simple reality is that Khamenehi has the power to neuter any president as he did to Mohammad Khatami and Hassan Rohani not to mention Mahmud Ahmadi-nejad, who announced in 2005 that women could go to soccer games, only to be humiliated when Khamenehi publicly reversed Ahmadi-nejad’s order. If Pezeshkian is to get any part of the Reformist agenda adopted as policy, he must first get Khamenehi to approve it.

Some think Pezeshkian has chosen to prostrate himself before the Leader in public in hope that in private he can then reason with the man that, for example, mandatory hejab is destroying public support for the regime. It remains to be seen if this will work. Many analysts think Khamenehi fully understands how the ban on women entering stadiums and the requirement for women to cover their hair are gigantic political negatives, but Khamenehi is always looking over his shoulder at the concerns of the senior clergy, which he cannot ignore.

Since his election, Pezeshkian has repeatedly appeared at Khamenehi’s side where he has constantly repeated a mantra of obeisance to the command of the Supreme Leader. That has made Pezeshkian look like a sell-out to many Iranians. But others see a politician who knows his limitations and is consciously pursuing a different tack than those of his predecessors recognizing that he can only do what the Supreme Leader allows him to do. Based on his campaign, there are at least six areas in which Pezeshkian wants to change things.

THE ECONOMY – The public is most concerned about the miserable economy, especially high inflation and high unemployment. Here Pezeshkian likely has a freer hand, as Khamenehi has little understanding of the issues and the clergy similarly has little theological interest in economics. Pezeshkian has said that economic problems are his first priority.

NUCLEAR POLICY – Khamenehi has already given Pezeshkian an opportunity to try to negotiate a return to the JCPOA though how much leeway the president will have on the details is unknown. The clergy has little interest in the details but many Majlis deputies have firm and hardline opinions.

WOMEN – The most sensitive political issue is hejab. Pezeshkian has made clear he doesn’t like the current policy. Wouldn’t you like to be a fly on the wall when he discusses this with the Supreme Leader?

Khamenehi knows that the issue presents a menacing political challenge to the regime. So, if Pezeshkian can discuss, “How can we address this political challenge” with the Supreme Leader rather than “How can I convince you to give in,” he may be able to get somewhere. THE

AUTHORITARIAN BENT – After the economy and women, much of the public is frustrated/furious over the regime’s authoritarian bent. Censorship and restrictions on the internet are major issues, as is the regime’s approach to minorities. Again, Khamenehi seems to recognize the problem. But he may never have discussed it with anyone like Pezeshkian and might be open to a serious discussion.

PASDAR POWER – This is in many ways just a part of the previous paragraph. Pezeshkian isn’t likely to get anywhere unless Khamenehi is willing to tell the Pasdaran to butt out.

This may first arise when Pezeshkian tries to address the economy. Many of the problems of the economy stem from the ways the Pasdaran profit at the public’s expense. Will Khamenehi allow Pezeshkian to take actions that reduce the income of Pasdar generals?

RESPONSE TO STREET PROTESTS – Pezeshkian is least likely to have much impact here. Khamenehi concluded decades ago that the failure of the Shah to crack down hard from the very beginning was the main reason the revolutionaries won.

Pezeshkian’s main hope is that he can improve the economy enough (by leveraging the Pasdaran out of the economy and by getting sanctions lifted) that street protests won’t start. In sum, Pezeshkian faces a major challenge and seems to have figured out unlike his predecessors that the only way to make changes is to induce Khamenehi to issue the orders that the president cannot. Saying that, of course, does not mean he can pull it off.

And his supporters may abandon him quickly if all they see is the president kowtowing to the Supreme Leader. In his first appeal to the Supreme Leader, news reports say Pezeshkian appealed after the assassination of Esmail Haniyeh that Khamenehi not approve any harsh military attack on Israel, cautioning that another attack could prompt Israel to respond with a crushing retaliation that would cripple much of Iran’s infrastructure and leave the economy even deeper in the hole.

The news reports said Khamenehi listened and remained non-committal. Outside the cabinet, Pezeshkian named Mohammad-Reza Aref as his first vice president, a very important if little noted position. The first vice president might be called a prime minister. He essentially runs the government on a day-to-day basis. continued from page one Aref was first vice president in President Mohammad Khatami’s first term and won kudos there. But in the 2016-2020 Majlis, he became the leader of the opposition and got failing marks from just about everyone.

He completely lacked any talent for political posturing and framing issues for the public and was mocked as the “Sultan of Silence.” But the job of first vice president doesn’t require those communications skills. Second, Pezeshkian named Ali Tayeb-nia as vice president for economic affairs, presumably making him the man who will guide economic reforms. Tayebnia was minister of the economy in President Hassan Rohani’s first term. And Pezeshkian named Hamid Pur-Mohammadi, another economist, as head of the Plan and Budget Organization (PBO).

Most revolutionaries don’t even like the PBO and they abolished it after the revolution. Reformists see it the same way the Shah did as a place for the country’s best brains to organize new and innovative policies to foster economic development. Pezeshkian also named Mohammad Eslami as vice president and head of the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran, the post he has held the last three years under the late President Raisi.

And the president named Zahra Behruz-Azar as vice president for women and family affairs, the one senior post traditionally reserved for a woman. Until now, she has been director of women’s affairs for the Municipality of Tehran. Vice presidents are not technically members of the cabinet and do not have to be approved by the Majlis. Often people who are likely to be blocked from cabinet posts by the Majlis are named vice presidents.

Meanwhile, an analysis of the voting by province suggested that Pezeshkian, a member of Iran’s Azeri Turkic minority, got a boost from his minority status. In the runoff election, Pezeshkian got his best voting percentages by a mile in Ardabil and East Azerbaijan, which just happen to be comprised almost entirely of Turkic-speaking residents.