December 25, 2015

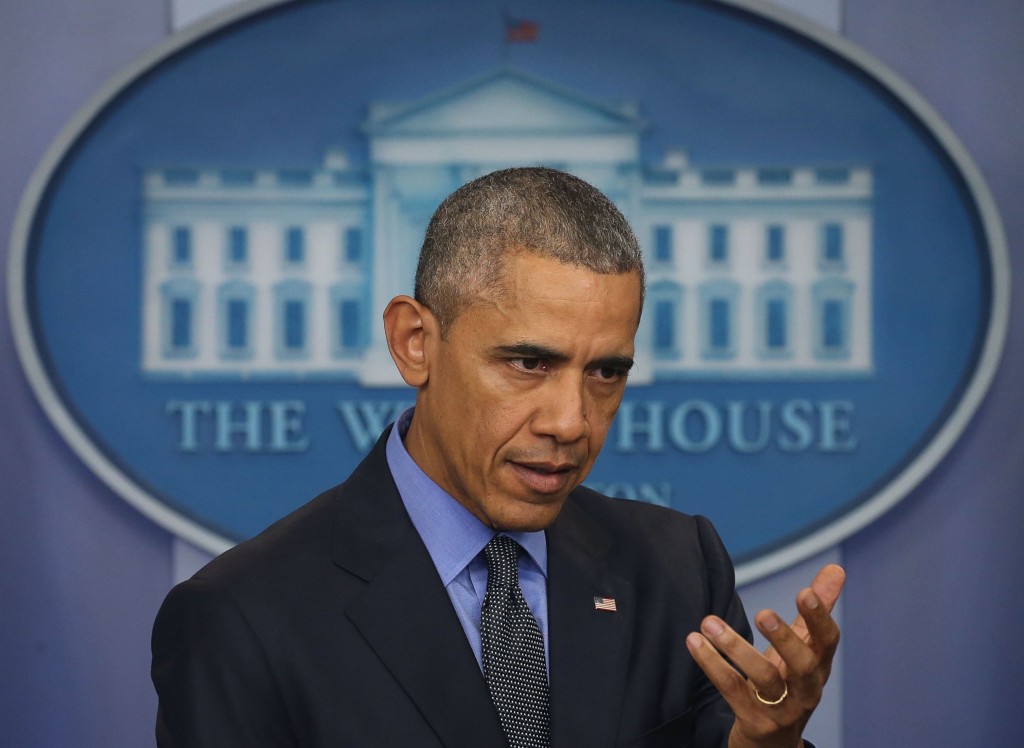

President Obama rejected a favorite GOP criticism that his foreign policy created chaos in the Middle East, saying the collapse of governments there is primarily the result of oppressive Arab government policies.

“We didn’t trigger the Arab Spring,” Obama said in a press conference Friday, defending his policy in Egypt, Libya and Syria since the pro-democracy uprisings that began in December 2010.

The president said he felt he had made the right call in Egypt, preventing a massacre by pushing dictator Hosni Mubarak to step down after days of massive protests.

The Islamic Republic continues to accuse Obama of supporting Mubarak, but the Islamic Republic did not declare public opposition to Mubarak until days after Obama called for him to step down.

Obama also stood by his decision to prevent Libyan leader Muammar Qadhafi from killing thousands of his own people by establishing a no-fly zone, but said the US and its partners should have worked quicker to establish a democratic replacement.

And he reiterated his opposition to Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad. “I think it is entirely right and proper for the United States of America to speak out on behalf of its values,” Obama said, referring to US policy on Assad. “And when you have an authoritarian leader that is killing hundreds of thousands of his own people, the notion that we would just stand by and say nothing is contrary to who we are, and does not serve our interests.”

Democrats tend to blame the current chaos in the Middle East on the George W. Bush invasion of Iraq in 2003. Republicans, on the other hand, tend to blame Obama for toppling dictators in the Middle East and trying to promote democracy. Top GOP candidates Donald Trump and Sen. Ted Cruz of Texas have both said the US should have stood behind Mubarak, Assad and Qadhafi.

But Obama supported neither of those views, saying the deposed Middle Eastern leaders would have faced popular challenges to their rule and potential collapse no matter what the US did.

The difference reflects the common tendency of Americans—regardless of party—to see events around the world as heavily influenced if not actually controlled by US actions. Obama treated that as nonsense.

“We did not depose Hosni Mubarak,” the president said. “Millions of Egyptians did because of their dissatisfaction with the corruption and author-itarianism of the regime.”

Obama said, “The notion that somehow the US was in a position to pull the strings on a country that is the largest in the Arab world, I think, is mistaken,” Obama said.

As for Libya, he said, “Those who now argue in retrospect we should have left Qaddafi in there seem to forget that he had already lost legitimacy and control of his country and—instead of what we have in Libya now—we could have had another Syria in Libya.”

The president conceded that Libya is hardly a model nation today. The country is split between two opposing governments fueled by rival Arab states. But Obama held that state of affairs was not an inevitable consequence of the intervention, but a result of America and its allies not planning swiftly enough for what would follow Qadhafi’s fall.

Obama spoke at unusual length in response to a question about his Middle East policies. Here is his full comment.

“There’s been a lot of revisionist history, sometimes by the same people making different arguments depending on the situation. So maybe it’s useful just for us to go back over some of these issues.

“We did not depose Hosni Mubarak. Millions of Egyptians did, because of their dissatisfaction with the corruption and authoritarianism of the regime. We had a working relationship with Mubarak. We didn’t trigger the Arab Spring. And the notion that somehow the US was in a position to pull the strings on a country that is the largest in the Arab world, I think, is mistaken.

“What is true is that at the point at which the choice becomes mowing down millions of people, or trying to find some transition, we believed, and I would still argue, that it was more sensible for us to find a peaceful transition to the Egyptian situation.

“With respect to Libya, Libya is sort of a alternative version of Syria in some ways, because by the time the international coalition interceded in Syria [he meant Libya], chaos had already broken out. You already had the makings of a civil war. You had a dictator who was threatening and was in a position to carry out the wholesale slaughter of large numbers of people. And we worked under UN mandate with a coalition of folks in order to try to avert a big humanitarian catastrophe that would not have been good for us.

“Those who now argue, in retrospect, we should have left Qadhafi in there seem to forget that he had already lost legitimacy and control of his country, and, instead of what we have in Libya now, we could have had another Syria in Libya now. The problem with Libya was the fact that there was a failure on the part of the entire international community—and I think that the United States has some accountability for not moving swiftly enough and underestimating the need to rebuild government there quickly. And, as a consequence, you now have a very bad situation.

“As far as Syria goes, I think it is entirely right and proper for the United States of America to speak out on behalf of its values. And when you have an authoritarian leader that is killing hundreds of thousands of his own people, the notion that we would just stand by and say nothing is contrary to who we are. And that does not serve our interests, because, at that point, us being in collusion with that kind of governance would make us even more of a target for terrorist activity.

“The reason that Assad has been a problem in Syria is because that is a majority-Sunni country and he had lost the space that he had early on to execute an inclusive transition, a peaceful transition. He chose instead to slaughter people. And once that happened, the idea that a minority population there could somehow crush tens of millions of people who oppose him is not feasible. It’s not plausible. Even if you were being cold-eyed and hard-hearted about the human toll there, it just wouldn’t happen. And as a consequence, our view has been that you cannot bring peace to Syria, you cannot get an end to the civil war unless you have a government that is recognized as legitimate by a majority of that country. It will not happen.

“And this is the argument that I’ve had repeatedly with Mr. Putin, dating five years ago, at which time his suggestion—as I gather some Republicans are now suggesting—was Assad is not so bad, let him just be as brutal and repressive as he can, but at least he’ll keep order. I said, look, the problem is that the history of trying to keep order when a large majority of the country has turned against you is not good. And five years later, I was right.

“So, we now have an opportunity … to find a political transition that maintains the Syrian state….

“And that is going to be a difficult process. It’s going to be a painstaking process. But there is no shortcut to that. And that’s not based on some idealism on my part; that’s a hardheaded calculation about what’s going to be required to get the job done.

“I think that Assad is going to have to leave in order for the country to stop the bloodletting and for all the parties involved to be able to move forward in a non-sectarian way. He has lost legitimacy in the eyes of a large majority of the country.

“Now, is there a way of us constructing a bridge creating a political transition that allows those who are allied with Assad right now—allows the Russians, allows the Iranians to ensure that their equities are respected, that minorities like the Alawites are not crushed or retribution is not the order of the day—I think that’s going to be very important as well.

“And that’s what makes this so difficult. Sadly, had Assad made a decision earlier that he was not more important personally than his entire country, that kind of political transition would have been much easier. It’s a lot harder now…. I do think that you’ve seen from the Russians a recognition that, after a couple of months, they’re not really moving the needle that much, despite a sizeable deployment inside of Syria. And, of course, that’s what I suggested would happen—because there’s only so much bombing you can do when an entire country is outraged and believes that its ruler doesn’t represent them.”