December 31, 2021

The new chief of state broadcasting has decided to loosen up news censorship by allowing the broadcast of news people already know about because it has been prominently reported on social media.

The point appears to be to improve the declining reputation of broadcast news by acknowledging stories most viewers already know about; refusing to cover such stories just feeds the public’s assumption that nothing carried on state news broadcasts can be trusted.

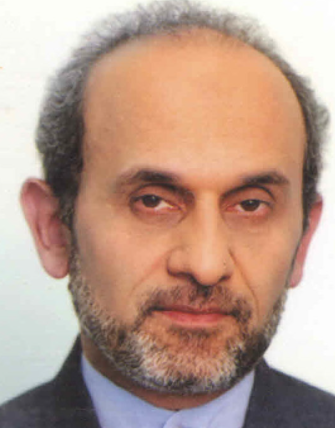

Last August, Supreme Leader Ali Khamenehi named Payman Jebeli, 53, as the new head of state radio and television broadcasting.

The change in news policy which presumably has Khamenehi’s approval became apparent to viewers and listeners in just the past few weeks as news programs carried stories on three news events that would normally have been ignored in the past because they are embarrassing for the regime.

They are: the inability of gasoline stations to sell subsidized gasoline after a cyberattack; the slapping attack on a new provincial governor general; and the exposure of Tehran’s mayor naming his son-in-law as one of his deputies.

The gasoline problem was readily apparent to drivers when they entered filling stations. The slapping attack was videotaped as it happened and the video was swiftly carried widely on social media. The story on the mayor’s son-in-law was also given wide attention on social media, although the mayor replied that his son-in-law would be working without pay.

The change in policy is not any liberalizing of state censorship. It is simply recognition of reality, that state broadcasting’s ignoring of major stories widely known by the public doesn’t hide those stories but just delegitimizes state news broadcasts as a whole.

Jam-e Jam, a daily newspaper published by state broadcasting, carried a special section of several pages describing the change and lauding Jebeli’s role in the shift.

A senior broadcasting official, Abdol-Reza Bavali, released an audio tape in which he asserted that the new policy was nothing new at all. Jebeli, clearly proud of his initiative, has since fired Bavali.

The censorship challenge is not a new one, but is greatly exacerbated by social media, which gives wide attention to stories the regime could at one time—before social media—have hidden.

The gasoline station problem brings to mind a story from a half century ago that the Shah’s censors tried to hide. In 1964, Tehran’s taxi drivers joined in a remarkably broad strike. The Information Ministry’s censors ordered that the newspapers not carry even one word about the strike. Publishers immediately realized they would have no credibility if they ignored a story anyone with eyes could see. The publishers got together and agreed jointly to ignore the censors. The next day, every newspaper carried a page one story on the strike.

Iran International said that state news broadcasts have been losing viewers steadily for more than a decade and Jebeli’s initiative is part of an effort to reverse that trend and try to draw people away from social media and foreign broadcasters.