June 16, 2017

John and Barbara Ratcliffe live in rural Britain with a bright yellow banner hanging on the hedge that reads: “Free Nazanin. Bring Our Girls Back.”

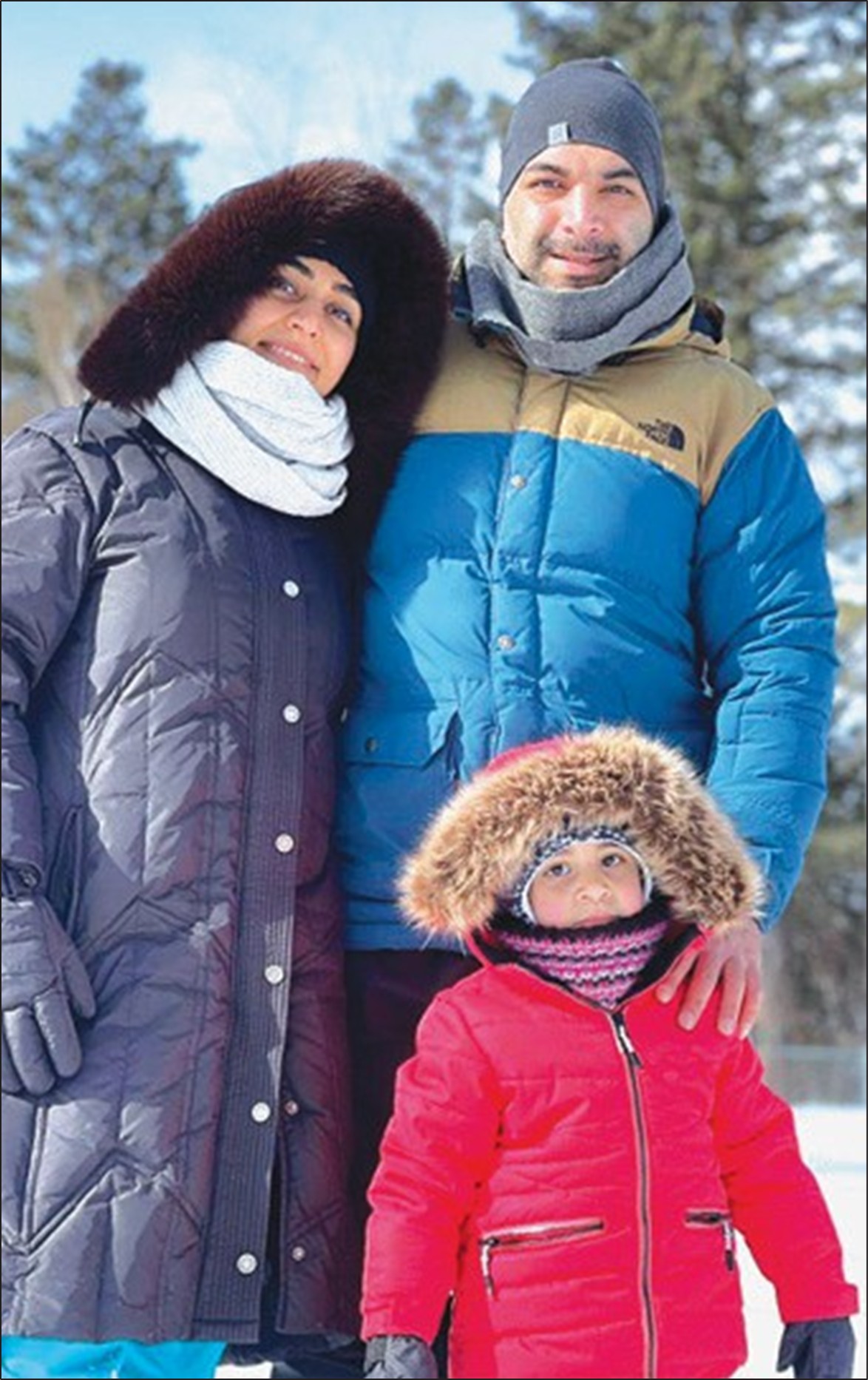

The “girls” are their daughter-in-law, Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe, a 38-year-old currently serving a five-year jail sentence in Iran, and her daughter, Gabriella, who turned three last Saturday, June 10.

The Ratcliffes celebrated with a family barbecue in the back garden; Gabriella joined them on Skype, to hear them sing her “Happy Birthday.”

The nightmare began April 3, 2016, when Nazanin was arrested in Tehran.

“It’s complete nonsense,” stresses Barbara, 66, a retired schoolteacher. “Basically, they’ve just kidnapped her.”

Gabriella has spent the last year of her life with her maternal grandparents in Tehran.

Her father, John and Barbara’s son, Richard, 42, has been forced to have a relationship with his daughter over Skype, and is only allowed rare phone calls with his wife. Living alone, the 42-year-old accountant spends most of his time campaigning to have his family returned to him.

“It’s ghastly because he’s our baby,” says Barbara. “I know he’s still a grown man, but he is. You think you can do everything for your children, but we can’t. He’s better at all this than us.”

The entire Ratcliffe clan—John and Barbara’s four children and five grandchildren, not to mention cousins, aunts and uncles—have banded together to fight for Nazanin and Gabriella’s return.

“We’re obsessed with it,” Barbara told The Telegraph of London. “Naz is constantly on our minds. I doubt we’ve had a day since she was detained that we haven’t mentioned her. We have a weekly Sunday night conference call with the family, and a fortnightly conference call to the Special Case Unit at the Foreign Office.”

The grandchildren haven’t been shielded from it. “Dylan, five and-a-half, draws Naz in a cage. While Mollie, the same age, is very worried Naz doesn’t have anything to eat.”

Her 67-year-old husband John, a practicing lawyer, adds: “It’s always in the background, because Nazanin’s part of our family. She calls us Mum and Dad. She’s the only one [of our children’s spouses] to do that, and she always has. She’s like a daughter to us.”

Barbara nods fiercely. “Even more so with all this. The Iranian government refuses to recognize her as a dual national, but tough. She’s ours and we love her.”

The Ratcliffes’ home is testament to this. A photo of Richard and Nazanin hangs with pride on their living room wall, while Gabriella’s toys (now played with only via Skype) are still scattered on the floor. A large stack of Christmas presents remains unwrapped behind the sofa.

“I naively thought they’d be home by Christmas,” says Barbara. “I bought Nazanin a bag—she loves handbags—and there’s a Wendy house in there for Gabriella. I thought it would be important for her to have some space of her own after everything that’s happened. I don’t know when I’ll be able to give it to her.”

As a full British citizen, Gabriella could legally be brought back home to the Ratcliffes at any point, but she is deliberately being looked after by her Iranian grandparents so that she can visit her mother once or twice a week in Evin Prison.

“It sounds silly to say that a three-year-old is providing support,” explains John. “But she is. She’s keeping Nazanin going. She’s keeping all of [Nazanin’s family in Iran] going really.”

The Ratcliffes could go to visit Gabriella, but fear the repercussions, and have accepted their son’s decision to allow Nazanin to determine their grand-daughter’s future. “Ricky [as his mother calls him] has said several times his job is to fight for Nazanin and Gabriella, and Nazanin is in control of Gabriella,” says Barbara firmly. “Nazanin’s cried several times to him, ‘Don’t take my baby from me. She’s the reason I stay alive,’ and we won’t.”

During her year of imprisonment, Nazanin has already had suicidal thoughts, and the only time that her parents-in-law received a phone call from her was last November, when she was at her lowest. “It was awful,” says Barbara quietly. “She was in tears saying ‘I’m so sorry I’m causing all this trouble.’ We said, ‘It’s not you.’

“At the time, we didn’t know that it was a bye-bye call and she was going on hunger strike. I was horrified.” The strike lasted several days, but “she stopped when she saw the effect it had on her mother, who fainted on seeing her, and Gabriella, who ran out screaming,” says Barbara. “She hasn’t promised she won’t do it full stop, but she’s promised she won’t for a while.”

The couple cannot speak regularly to Nazanin—she is only allowed rare phone calls, which she saves for Richard—but they do make sure they speak to Gabriella every day on Skype. “It’s really important for me to do that,” says Barbara. “Our slot is 6 p.m., so we speak then, daily—unless she’s been grumpy or wants to watch television instead.”

Back when Gabriella lived with her parents in London, Barbara would see her granddaughter regularly and play games, cook and dance with her. Yet in the last year, Gabriella has lost her grasp of English and speaks just Farsi. The only way her grandmother can talk to her is with Nazanin’s younger brother, Mohammed, translating.

“He’s brilliant—who’d want a middle-aged woman phoning them up every day?” quips Barbara. But she is serious when she talks about her need to keep up her relationship with Gabriella. “As long as she sees us, that’s all that matters; that she knows who Granny is.”

Her grandparents sent her a birthday present—an expensive life-sized doll that they bought for her back when Richard and Nazanin had been thinking about having another child. A British politician took the doll to Tehran for them.

“She likes her dolly,” smiles Barbara. “And a knitted incey wincey spider, a hideous thing I knitted; she liked that. She’s perfectly all right—but at the same time she’s also not, because she’s been taken from her mum and dad. She’s turned from an English baby to an Iranian little girl and she’s growing up fast. She’s so much more mature than any of our other grandchildren were at that age.

“I can’t help thinking when she’s a bit olderÖ well, she so loves her Iranian grandparents, but if she hears people can just be taken and put in prison in Iran, she’ll be so upset about that family being in danger. I don’t know how it’s all going to be explained to her.”

Nor do the Ratcliffes have any idea when their family will be reunited again. Though Nazanin still has four years left in prison, they desperately hope that the British government will manage to secure her release before then.

They try hard to not think too deeply about the amount of time that has passed since their son last saw his wife, let alone his little girl.

“What’s the point?” sighs Barbara. “The time has gone. If I do think about it, I’m very bitter. Why should they have all missed out on this time together? Why?”