September 23, 2022

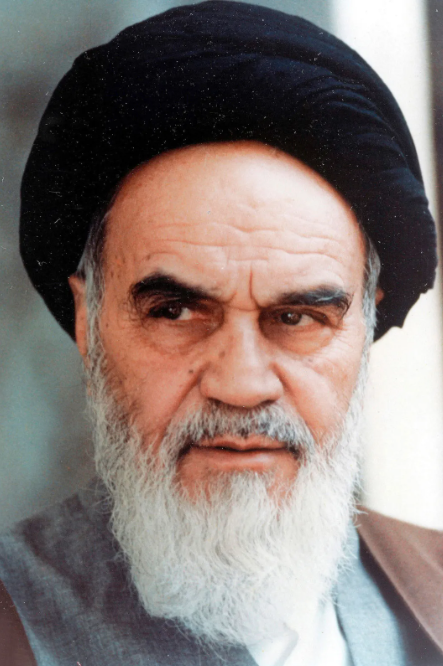

It took a third of a century, but Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini’s effort to induce a Muslim to kill Salman Rushdie has finally materialized—although, like so many other schemes by the Islamic Republic, it failed to succeed.

Khomeini issued his death fatva on Valentine’s Day of 1989. It was an edict that found Rushdie guilty of blasphemy for writing “The Satanic Verses,” a novel that mocked the Prophet of Islam, and proclaimed that any Muslim who “is killed doing this will be regarded as a martyr and will go directly to heaven.”

One dream sequence in the novel presents the figure of a fanatic expatriate religious leader, the “Imam,” in a late 20th Century setting, which is widely seen as satirizing Khomeini himself.

Despite what is often said, the book does not take direct aim at Islam or its Prophet. Those sections that have caused the greatest controversy are contained within the dreams or nightmares of a character who is in the grip of psychosis.

The book prompted opposition across the Islamic world after its release in September 1988. But it took five months before Khomeini issued his fatva.

Many argue that Khomeini acted, not out of religious fervor, but purely for political reasons, as part of his effort to gain leadership of the Islamic world. Andrew Anthony wrote in The Observer of Great Britain, “The Satanic Verses affair was less a theological dispute than an opportunity to exert political leverage. The background to the controversy was the struggle between Saudi Arabia and Iran to be the standard bearer of global Islam. The Saudis had spent a great deal of money exporting the fundamentalist or Salafi version of Sunni Islam, while Shiite Iran, still smarting from a calamitous war and humiliating armistice with Iraq, was keen to reassert its credentials as the vanguard of the Islamic revolution.”

Khomeini’s fatva quickly overshadowed the Saudi efforts and gave Khomeini new prominence—not as the leader of Islam, however, but as the mouthpiece for a violent strain of Islam.

Many in Iran were embarrassed by the fatva, seeing that it cast Iran as bloodthirsty. The president of Iran at the time, Ali Khamenehi, issued a statement downplaying the fatva and insisting there was no Iranian effort to incite the murder of Rushdie. That infuriated Khomeini, who swiftly contradicted Khamenehi.

The next decade was a dangerous and isolating time for Rushdie. He was protected around-the-clock by British government bodyguards, and moved each time the security services became aware of one in a series of plots to kill him.

Rushdie sought a way out. On Christmas Eve 1990, he issued a statement bearing witness that “there is no God but Allah, and Muhammad is his last prophet.” Claiming to have renewed his faith in Islam, he said he did not agree with any character in “The Satanic Verses” who “casts aspersions … upon the authenticity of the holy Qoran, or who rejects the divinity of Allah.”

Rushdie also said he would not release a paperback of the book. That evening he was so disgusted with himself that he was physically sick, he said. The playwright Arnold Wesker, a Rushdie supporter, said: “The religious terrorists have won.” A close friend, Christopher Hitchens, recalls: “I told Salman that it didn’t make any difference to my support for him but that I didn’t think it would ‘work’ and that I didn’t think it was dignified. I think he felt much better after he re-apostasized.”

Years later Rushdie would publicly say it was the biggest mistake of his life, a “deranged” moment when he had hit rock bottom. In the event, it made no difference. Though Khomeini was now dead, the Iranian clergy confirmed that Rushdie still had to be killed.

The Khomeini edict not only condemned Rushdie to death but everyone involved in producing and circulating the book. In the year after the fatva was issued, six bookshops in England were bombed. Then Hitoshi Igarashi, Rushdie’s Japanese translator, was stabbed to death and Ettore Capriolo, the Italian translator, seriously injured in another knife attack. In 1993 William Nygaard, the publisher in Norway, was shot and injured, and Aziz Nesin, the Turkish translator, was the target of an arson attack on a hotel in Turkey that left 37 dead.

Rushdie was born in Bombay, now Mumbai, into a liberal Muslim family. His early education was at a Christian school there, before his family sent him to Rugby School in England and then on to the University of Cambridge. So, his education was entirely in English. In 2000, Rushdie moved to New York and in 2016 took US citizenship.

The close protection, which virtually imprisoned Rushdie, ended after almost a decade, and the author has traveled widely since then with only minimal protection at his many public appearances. Until this summer, there was no effort to attack him.

In an interview just weeks before the stabbing, Rushdie said that his life had become “relatively normal.”

After Khomeini’s death, just four months after issuing the fatva, the Islamic Republic devised a policy it hoped would satisfy the angry West without offending its own hardliners. That policy said the fatva was irrevocable but that the Iranian “government” would do nothing to carry it out. That remains state policy to this day. The Iranian government tries to avoid mentioning the fatva, though Khamenehi periodically re-endorses it, saying as recently as 2019 that the fatva remains “solid and irrevocable.”

Khamenehi has so far said nothing about the Chautauqua attack on Rushdie.