November 22-2013

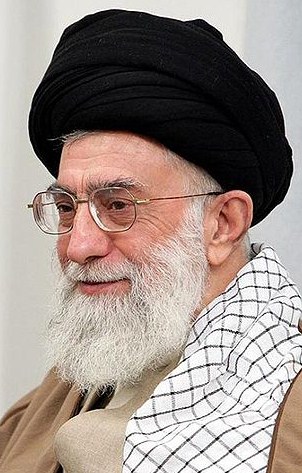

Supreme Leader Ali Khamenehi has amassed power in much the same way as Reza Shah did when he established the Pahlavi Dynasty—by confiscating the property of his opponents.

. . . the teacher

A huge, three-part series published last week by the Reuters news agency documents examples of how an agency under Khamenehi’s command has come to amass a fortune in real estate, industry and business—including a condom-manufacturing firm.

The agency was created in 1989 by Ayatollah Khomeini just two months before his death. He assigned two aides—one of whom was Mehdi Karrubi, the former presidential candidate now under house arrest—to use the agency to gather together abandoned property and property being seized from regime opponents with the goal of distributing the wealth to charity. The agency was then to be dissolved after two years.

But Khamenehi never dissolved the agency. Reuters calculates that it has amassed wealth well in excess of $95 billion. Reuters said it found valuations of some properties totaling that much, but that it could find no way assess the value of many other properties.

The organization is named Setad Ejrai-e Farman-e Hazrat-e Imam, the Headquarters for Executing the Order of the Imam. It is known simply as Setad or Headquarters.

Khamenehi has used it to amass assets that rival the holdings of the Pahlavis, whose wealth was based on seizing the property of previous Qajar Dynasty.

Reuters said Setad’s portfolio includes banks, farms, cement companies, not to mention residences seized from Iranians who fled abroad after the revolution.

Reuters emphasized that it found no evidence Khamenehi ever put these assets to personal use. Instead, Setad’s holdings were used to underpin his grip over the country—and over potential rivals.

Oddly, the Islamic Republic waited a full week before responding. The Islamic Republic News Agency (IRNA) ran an editorial Tuesday saying Reuters was trying to tarnish “the pillars of the Islamic revolution.” But the editorial did not respond to any of the points made in the Reuters series. Instead, it argued that Setad played a key role in alleviating poverty. The Reuters series, however, said some portion of Setad’s profits were dedicated to help the poor.

The main point of the series was Reuters’ assertion that Setad is used to leverage both political and economic power in the hands of Khamenehi.

. . . the student

Reuters said that several years ago, Khamenehi directed a study of how strong economic powers succeeded in growing quickly. The study pointed to the power of business conglomerates, especially those in Japan, South Korea and the United States. Setad, said Reuters, decided it was superbly positioned to fulfill that role for Iran.

Reuters’ investigation unearthed how the revolutionary regime systematically legitimized the practice of confiscation and gave Setad control over much of the seized wealth. “The Supreme Leader, judges and parliament over the years have issued a series of bureaucratic edicts, constitutional interpretations and judicial decisions bolstering Setad,” Reuters said. “The most recent of these declarations came in June, just after the election of Iran’s new president, Hassan Rohani.”

Reuters said Setad has amassed much of its portfolio by claiming in the courts—“sometimes falsely”—that properties have been abandoned.

Iranians whose properties have been seized by Setad, as well as lawyers who have handled such cases, dispute the argument that the organization is acting in the public interest. They described to Reuters what amounts to a methodical moneymaking scheme in which Setad obtains court orders under false pretenses to seize properties, and then often pressures owners to buy them back or pay huge fees to recover them.

“The people who request the confiscation … introduce themselves as on the side of the Islamic Republic, and try to portray the person whose property they want confiscated as a bad person, someone who is against the revolution, someone who was tied to the old regime,” said Hossein Raeesi, a human-rights attorney who practiced in Iran for 20 years and handled some property confiscation cases. “The atmosphere there is not fair.”

Ross K. Reghabi, an Iranian lawyer in Beverly Hills, California, told Reuters the only hope to recover anything is to pay off well-connected agents in Iran. “By the time you pay off everybody, it comes to 50 percent” of the property’s value, said Reghabi, who says he has handled 11 property confiscation cases involving Setad.

An Iranian Shiite Muslim businessman now living abroad, who asked to remain anonymous because he still travels to Iran, said he attempted two years ago to sell a piece of land near Tehran that his family had long owned. Local authorities informed him that he needed a “no objection letter” from Setad.

The businessman said he visited Setad’s local office and was required to pay a bribe of several hundred dollars to the clerks to locate his file and expedite the process. He said he then was told he had to pay a fee, because Setad had “protected” his family’s land from squatters for decades. He would be assessed between 2 percent and 2.5 percent of the property’s value for every year.

Setad sent an appraiser to determine the property’s current worth. The appraisal came in at $90,000. The protection fee, he said, totaled $50,000—not 2.5 percent but 55 percent.

The businessman said he balked, arguing there was no evidence Setad had done anything to protect the land. He said the Setad representatives wouldn’t budge on the amount but offered to facilitate the transaction by selling the land itself to recover its fee. He said he hired a lawyer who advised him to pay the fee, which he reluctantly did last year.

This was not the only encounter the businessman’s family had had with Setad. He said his sister, who lives in Tehran, recently told him Setad representatives had gone door-to-door at her apartment complex, demanding occupants show the deeds for their units.

Several other Iranians whose family properties were taken over by Setad described in interviews how men showed up and threatened to use violence if the owners didn’t leave the premises at once. One man said he had been told how an elderly family member had stood by distraught as workmen carried out the furniture from her home.

According to this account, she sat down on a carpet, refused to move and pleaded, “What can I do? Where can I go?”

“Then they reached down, lifted her up on the carpet and took her out.”

But Reuters said Setad generally tries to leave a seemingly legal trail to justify property confiscations, perhaps because the revolution condemned property confiscation by the Pahlavis. Khomeini himself cited such offenses as a reason for overthrowing the Shah in 1979.

In October 2010, Kha-menehi even discussed how bad the old regime had been because of its confiscations.

“Our people were living under the pressure of corrupt, tyrannical and greedy governments for many years,” Khamenehi told officials in Qom. The Shah’s father “grabbed the ownership of any developed piece of land in all parts of the country. They accumulated wealth. They accumulated property. They accumulated jewelry for themselves.”

Actually, there is nothing odd about the current regime pursuing policies it once condemned. For example, the Tehran Metro, the highway from Tehran through the mountains to the Caspian and the planned chain of nuclear power plants were all condemned by the revolution as the Shah’s wasteful “prestige” projects. All were canceled in 1979—and all have been revived since.

Iranian attorneys who have battled Setad and who were interviewed by Reuters said the new regime has also outdone the old regime in confiscations.

The regime makes aggressive use of the law to take property from citizens—in particular, Article 49 of the Constitution, which provides for seizing illicit assets from criminals.

“It is a very powerful tool,” said Mohammad Nayyeri, a Britain-based lawyer who worked on several property confiscation cases involving Setad before leaving Iran in 2010. “It opens the door to corruption. There is no limitation. The private ownership and private life of people are not respected.”

Another Constitutional provision, Article 45, also bolsters Setad. It deals with public property, giving the government the right to use “abandoned” land and “property of undetermined ownership.”

Shaul Bakhash, an Iran historian at George Mason University in Virginia, told Reuters, “Article 49 is so broadly written that it allows confiscation and expropriation on the flimsiest of excuses.” He said property of his own was confiscated by court order in 1992.

Wholesale expropriation of wealth became a hallmark of the early republic. Bonyads or foundations were among the first beneficiaries of this transfer of wealth. One of the biggest was Bonyad-e Mostazafin, or the Foundation of the Oppressed, which took over many of the royal family’s assets. It remains in business.

“This situation in reality created a struggle and a sort of competition between the revolutionary units and institutions for each to find the best properties and introduce them to the court as candidates for confiscation,” said Raeesi, the human-rights attorney.

In 1982, with factions and organizations feuding over properties, Khomeini tried to control the chaos, issuing a decree that banned confiscations without a judge’s order. “It is unacceptable and intolerable that in the name of the revolution and being revolutionary-minded, God forbid, an injustice should be done to someone,” Khomeini declared in the order.

Two years later, in 1984, parliament created a special class of property confiscation courts—dubbed “Article 49 Courts”—in each province. They were a branch of the Revolutionary Courts.

The Article 49 courts continue to operate today, but they failed to end the free-for-all. “In practice, the establishment of the Article 49 courts systematized and continued the expropriations, and even today the confiscations continue,” Raeesi said.

In April 1989, Khomeini directed two senior officials to take over all “sales, servicing and managing” of properties “of unknown ownership and without owners.” The revenues were to be spent on Sharia issues “and as much as possible” to help seven bonyads and charities he named. The officials were to use the money to support “the families of the martyrs, veterans, the missing, prisoners of war and the downtrodden.”

By the early 1990s, courts were seizing assets and turning them over to Setad, according to documents reviewed by Reuters. The organization began keeping funds from property sales, rather than redistributing all the proceeds. It isn’t clear when Setad began retaining funds or what percentage of the revenue it keeps, Reuters said.

In 1997, when reformist Mohammad Khatami was elected president, the Judiciary moved to shield Setad from scrutiny. The General Inspection Office (GIO) is an anti-corruption body. That year, a government legal commission declared that the GIO had no right to inspect Setad.

Setad still faced competitors. Among its main rivals for seized assets, according to attorney Mohammad Nayyeri, was another organization: Sazeman-e Jamavari va Foroosh-e Amval-e Tamliki, or Department for the Collection and Sale of Acquired Property, which is controlled by the Economy Ministry. In 2000, the Judiciary adopted a bylaw granting Setad exclusive authority over property taken in the name of the Supreme Leader.

The regime’s privatization program would appear to be a threat to Setad’s vast holdings. But privatization actually helped Setad accumulate even more wealth. In 2009, Setad emerged as the victor in Iran’s biggest state asset sale, the privatization of the Telecommunications Co of Iran (TCI).

Through a subsidiary, Reuters said, Setad bought a 38 percent stake in a consortium that was awarded majority control of the telecommunications provider. The other big winner was the Pasdaran (Revolutionary Guards), which controlled most of rest of the winning consortium.

But Setad had been drawing attention from the Reformist wing of the establishment. During Khatami’s second term, some Majlis deputies sought to investigate Setad, according to Nayyeri. The Council of Guardians quickly issued a declaration that Setad was beyond Majlis scrutiny.

The Majlis elections of 2008 ousted the Reformists and brought in a majority of conservatives. In one of its first steps, the new Majlis amended its bylaws to limit its own power to audit institutions under the Supreme Leader’s supervision.

Setad today remains veiled from the public eye. It is led by Mohammad Mokhber, a Khamenehi loyalist who is also the chairman of Sina Bank. The European Union sanctioned him in 2010 but lifted the sanctions last year, without explanation. Just this past June, the US Treasury Department sanctioned Setad and 37 of its subsidiaries.

Setad reveals little about its income, expenditures or staffing. Its headquarters is in a large gray concrete building with small windows in the heart of Tehran’s commercial district.