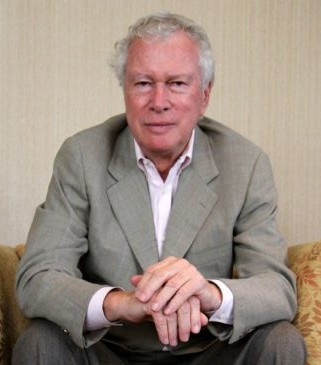

Kenneth Taylor, the Canadian ambassador to Iran who sheltered and arranged the escape of six American diplomats during the hostage crisis, died in a New York hospital last Thursday. He was 81 years old and succumbed to cancer.

Taylor’s place in history was once summed up as: “The right man in the wrong place at the right time.”

He became an overnight hero to both Canadians and Americans in 1980. He became a human symbol of the closeness of the two nations who live on either side of what both countries proudly call “the longest undefended border in history.”

His role was heralded in 1980 and got renewed attention in the 2012 Hollywood blockbuster “Argo,” though many Canadians steamed that Hollywood minimized Canada’s and Taylor’s role in saving the six.

When Canada’s and Tay-lor’s role first became known in 1980, there was an outpouring of appreciation in the US for all things Canadian—not just hockey.

The mood in the United States was “euphoria,” The New York Times said. The Christian Science Monitor said “The Canada Caper” was “a dramatic reminder that the American people still do have more than fair-weather friends in the world.”

The American government awarded Taylor the Congressional Gold Medal. Canada made him an Officer of the Order of Canada. He became a familiar face on television across North America.

Canada took advantage of the adoration for him in the United States by appointing him as consul general in New York, from which platform he spoke often to Americans.

In 1984, he left government service but remained in New York as a vice president of RJR Nabisco. In 1990, he founded Global Public Affairs, a consulting firm that offers strategic advice to foreign governments.

Taylor died at the New York Presbyterian Hospital with family members by his side. He had been ill with colon cancer for two months.

Taylor was born in Calgary October 4, 1934. From the beginning of his life, he excelled at everything he did. He was always a fine student and athlete, had many friends and, though diligent, had a signature air of ease about most things.

In an obituary, the Ottawa Citizen said, “He loved Calgary, but often felt a hunger for exposure to the wider world.”

In 1959, after studies at the University of Toronto and University of California at Berkeley, he joined Canada’s Foreign Service as a trade counselor. He rose quickly and within 15 years was head of the Canadian Trade Commissioner Service.

In 1977, he applied to become an ambassador. He asked specifically for Iran, drawn by the rapidly changing country that was just beginning to develop a significant trade relationship with Canada.

But he wasn’t there long before the Shah was gone and trade became a minor matter. On November 4, 1979, a band of students climbed over the wall of the American embassy in Tehran and took possession of it.

The students managed to capture more than 60 hostages, most at the embassy’s chancery, though after several were released, 52 remained for the duration of the 444-day crisis.

Six Americans who worked at the consulate, a separate building in the 27-acre compound, managed to escape. Eventually, they found sanctuary in the residences of Taylor and of immigration officer John Sheardown.

They would remain in hiding for 79 days before managing to leave Iran under passports issued to them by Canada’s Department of Foreign Affairs and the cover story that they had come to Iran to make a film. The cover story, with its associated documents, was provided by CIA exfiltration expert Tony Mendez. Though this task took Mendez only a couple of days, his role, as played by Ben Affleck in “Argo,” was made the center of the film.

Two years ago, Jimmy Carter, the president in office during the embassy seizure, told CNN, “Ben Affleck’s character was only in Tehran a day and a half. The main hero, in my opinion, was Ken Taylor Ö who orchestrated the entire process.”

Affleck himself, stung by criticism of the film’s distortions, wrote a new postscript that appears in the film as released: “The involvement of the CIA complemented efforts of the Canadian embassy to free the six held in Tehran. To this day the story stands as an enduring model of international co-operation between governments.”

On January 27, 1980, Mendez and the six American diplomats easily passed through security at Tehran’s Mehrabad Airport. There was no runway chase as depicted in the film.

Later that same day, Taylor and the few embassy staff who remained at that point flew out of Iran.

Montreal’s La Presse broke the story the next day and it quickly became a media sensation.

Taylor made numerous tours of Canada and the US to speak about the Canadian caper—and audiences were always eager to hear him. He appreciated his reception and often said that he loved how Americans, for a time, treated all Canadians as special people. As he later said, Canadians in the US “couldn’t buy a beer. They couldn’t get a traffic ticket. They got free rides on buses.”

In 2010, Trent University professor Robert Wright published a full account of Taylor’s time in Iran entitled “Our Man in Tehran: Ken Taylor, the CIA, and the Iran Hostage Crisis.” Some elements of the book were surprising. Wright related how Taylor had effectively spied for the Americans, providing information about what was happening on the embassy grounds during the 444-day crisis and providing material to assist in the abortive rescue attempt that the Americans mounted. This intelligence activity, if revealed earlier, could have proved far more dangerous to Taylor than his sheltering of a few American embassy officials.

Taylor said he was amused by the heightened reaction to these revelations. “There’s a certain sinister or romantic or Hollywood-type element to something that is done in secret, particularly if it’s done in a time of war, revolution or what have you.” In any case, Taylor was having nothing to do with any romantic notions about his own role. As he told a reporter, “I’ve wondered if I’m not more like Austin Powers than James Bond.”

Taylor said the whole escapade had begun as a matter of duty. “We were doing what I would expect any Canadian diplomat would do,” he once said.

His widow told the Canadian Press, “There was no second thought about it. He just went ahead and did it.”

Taylor liked to recall a letter he received from an 11-year-old in San Francisco: “Dear Canada, My name is Alan. Thanks for the six. When are you going back for the rest?”

Taylor is survived by his wife, Pat, a medical researcher whom he wed 55 years ago, and their son, Douglas.