March 26, 2021

An Iranian physician has rapidly been awarded Bulgarian citizenship when it was realized a Bulgarian law was about to force the remote hospital he has rescued to fire him.

The doctor and his plight became a national issue and political leaders soon understood what was happening and rushed to embrace the doctor and save his role running the hospital.

The doctor and his plight became a national issue and political leaders soon understood what was happening and rushed to embrace the doctor and save his role running the hospital.

For six years, Dr. Abdullah Zargar-Shabestari has been the director of Isperih General Hospital, a once-struggling municipal health facility close to the Romanian border.

He was told he had to go because of a change to the Law on Public Enterprises, which barred non-Bulgarian citizens from occupying managerial posts at public institutions. Dr. Zargar-Shabestari had applied for citizenship in 2015 but had been unsuccessful.

Locals were horrified and launched a petition calling for him to be granted citizenship. The petition drive skyrocketed in January with more than 20,000 Bulgarians adding their names and making the drive a national news story. That’s a lot when you consider that tiny Isperih only has 10,000 inhabitants. But the hospital is the only one in the region and serves people who live far from the town.

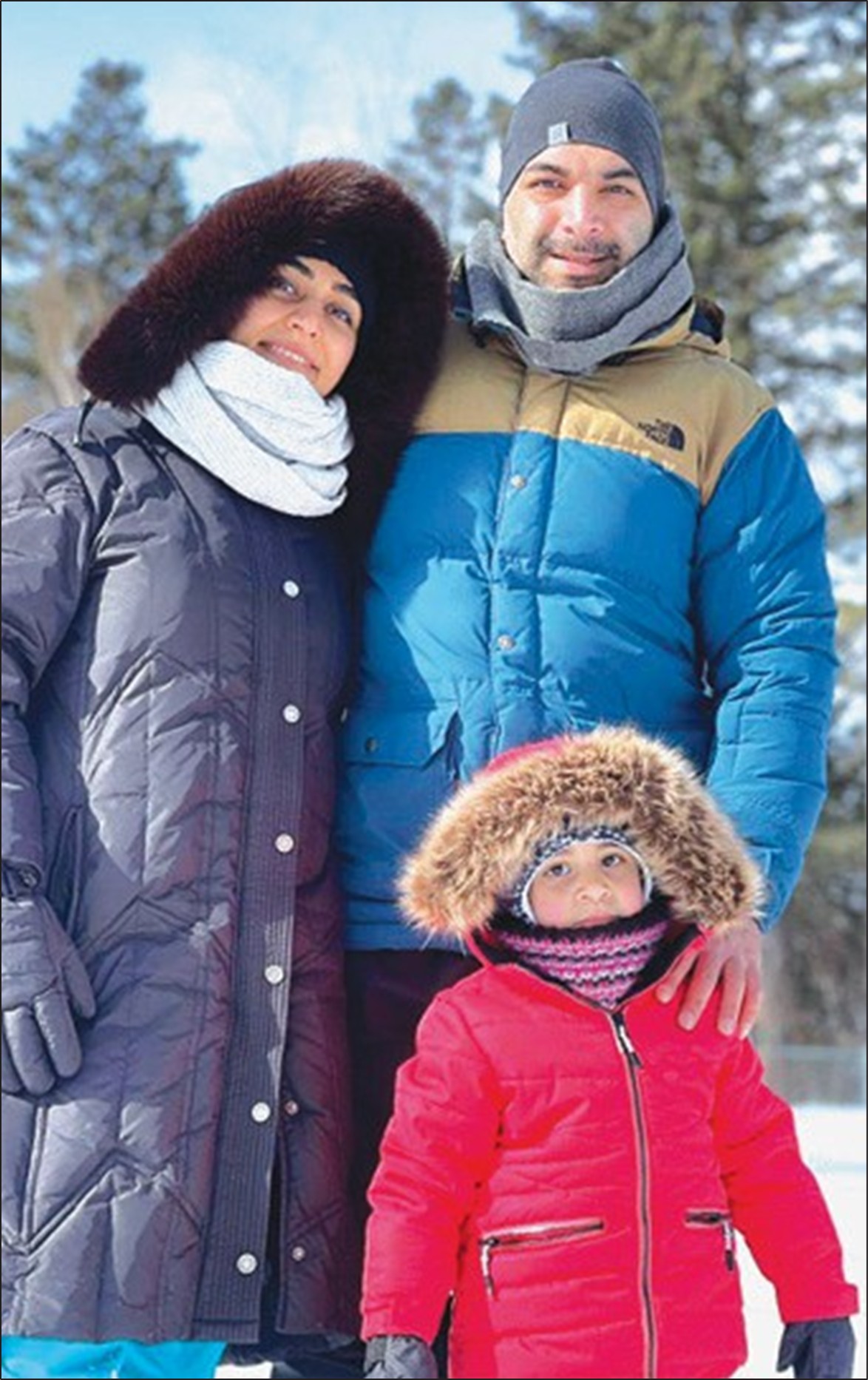

Politicians of all stripes were alerted. In a matter of days, Vice President Iliana Iotova signed a decree conferring Bulgarian citizenship on the 52-year-old surgeon from East Azerbaijan. On February 7, Dr. Zargar-Shabestari received his citizenship at a ceremony in Sofia in the presence of the Bulgarian ministers of justice and health, unprecedented national recognition for a doctor from a remote corner of the country.

Abdullah Zargar-Shabestari was born in Shabestar, East Azerbaijan, in 1969 to a family of Azeri jewelry shop owners. Looking back, he says, this mercantile upbringing may have had something to do with his success in his role as hospital director.

“My family are all businesspeople,” he told IranWire. “I’m good at business, despite the fact that I don’t like it. It’s in my genes. Half of the job of a good chief executive is being a good businessman.”

At the age of about 18, Abdullah was fired from managing one of the family’s stores because of being over-generous with the amount of gold he gave to customers: “I often gave customers a bit extra,” he says.

He studied Russian in Baku, which was then part of the Soviet Union, before moving to Moscow to train as a doctor at the Medical Academy. From there, he moved to Germany in 1994. “At the time,” he says, “as an Iranian, there was no chance for me to specialize. So, I went to England. But again, it was difficult for me to get hired. I decided to go to Bulgaria for a PhD.”

Dr. Zargar-Shabestari arrived in Bulgaria in 2004 and worked for a long spell as an orthopedic surgeon in Varna. In 2012, he briefly returned to the UK and the next year an acquaintance told him a hospital in Bulgaria was “nearly bankrupt” and in need of a new director.

“He said nobody would take the chief executive role,” Dr. Zargar-Shabestari remembers, “because it was getting worse and worse there. I didn’t know whether to sign the contract, or to drive down and see what was happening. But I went – and I saw a disaster. I don’t know how to explain it. I thought to myself, ‘This may be a lifetime chance to do something nobody else wants to do’.”

Isperih General Hospital had been struggling for years. The building was dilapidated, the facility had mounting debts, and medical staff were leaving in droves.

With the blessing of the then-governor of Razgrad province, he put himself forward for the top role. In Bulgaria such appointments need to be approved by the city council and, when it came to the vote, he remembers, “some of them were laughing at me. They said, ‘There’s no doctor we will find [for this position] from Iran.’ They thought it was funny. But they didn’t have any choice. Since then, all of them have become friends with me. Now I feel that this is my home.”

One of the first tasks was to secure funding. Zargar-Shab-estari managed to secure a 2-million-euro grant from the European Union. “In the small area of Bulgaria where I live, that’s a lot of money.”

They spent the money on sanitation and a full range of equipment including CT scanners, endoscopy equipment and ultrasound scanners. Within a year, the hospital was then able to re-secure subsidies from the Bulgarian government. “The first time I went to the Ministry of Health to apply,” Dr. Zargar-Shabestari recalls, “they mistook us for a big hospital in Romania because they didn’t even know the name!”

In time, Isperih built its first fully-equipped intensive care unit. Coaxing specialist doctors into moving to Razgrad province was hard, but luckily, Dr. Zargar-Shabestari says, “I found and encouraged some people who had the internal motivation for it.”

The improvements kept coming: in 2018 the hospital received a donation of beds, physiotherapy baths and other equipment from colleagues in Germany, and in 2019 it installed a range of new devices including ventilators, ultrasound scanners and a new set of cribs for the children’s ward.

Planned changes to the Law on Public Enterprise had first been announced by the Bulgarian government in late 2019. It was not until late 2020 that Dr. Zargar-Shabestari and his colleagues realized it would apply to him, too: after the grace period expired in February 2021, he would be forced to step down. But locals were having none of it and started the petition drive.

Like most European states, the process of naturalizing in Bulgaria is an arduous one – perhaps particularly so, as any application requires the assent of the Bulgarian Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Justice, and a cross-party group of Bulgarian politicians who do not usually see eye-to-eye, before finally going before the presidency. The fact that this Iranian doctor’s case was advanced and signed off in just five days after the petition was unveiled was a minor miracle.

There are, he points out, many other doctors in Bulgaria still waiting for citizenship who did not have the support of TV coverage and an adoring local populace. Among them, scattered across Europe and further afield, are countless other Iranian-born doctors and nurses.

For his part, Dr. Zargar-Shabestari says he is content for now to remain where he is. “Everybody in Bulgaria knows the hospital now. It was a wave, and we managed to catch it. I can help more people in this position. Nothing compares to it.”