and the Islamic Republic might actually be coming out on the plus side.

The EU is phasing out purchases of Iranian oil while China, Japan and India, the three biggest buyers of Iranian oil, have all shifted part of their Iranian purchases to other producers.

And the only country in the world that is known to be 100 percent dependent on Iranian crude—Sri Lanka—is now buying no Iranian oil at all.

Sri Lanka is a minor buyer, so its abandonment of Iran means little economically. But it is a major political abandonment. And, furthermore, it shows how easy it can be to shift to other sources, despite the fretting of many commentators who seem to think that refineries are only made for one source of oil and are able to change only at vast expense and after much time.

Sri Lanka has been close to Iran in recent years when its poor human rights record led many other countries to shun it. Its single oil refinery was refitted by Iran and was designed to deal with Iranian crude. It got good credit terms from the Islamic Republic and bought all of its crude from Iran.

Just a few weeks ago, officials publicly bewailed their fate and worried out loud that the new sanctions would make it hard for them to get that Iranian crude.

But last Tuesday, Sri Lankan Energy Minister Susil Prem-ayatantha told Parliament, “We no longer purchase fuel from Iran.” He didn’t say from where Sri Lanka was now buying crude. And he did not complain of any problems shifting to non-Iranian crude.

But the bigger question is what is happening to Iranian revenues. Only the Iranian government truly knows—and it isn’t saying.

Last week, Ian Taylor, the chief executive of Vitol, the world’s largest oil trader, said he suspects Iran is doing quite nicely thanks to surging oil prices.

“The Iranians now want the price as high as possible as they’ve got less volumes to sell,” Taylor said. “I reckon they are probably quite close to winning based on the numbers.” But he gave no numbers.

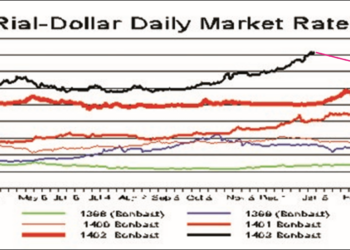

President Obama signed the new US sanctions into law New Year’s Eve and the EU imposed its strong new sanctions January 23. Starting after January 1, the price of an OPEC barrel ended a period of stagnation and suddenly took off. Since January 1, the price has risen 13 percent.

Thus, as long as Iran’s oil sales have not fallen more than 13 percent, it is doing all right financially. But no one outside Iran yet knows by how much oil sales have fallen.

The loss of the EU market will mean the loss of about 18 percent of Iran’s crude sales by July 1. India, Japan and South Korea are all trying to figure out how much they will have to reduce purchases to keep American sanctions away from their door. They all seem to have conceded the figure will be above 10 percent. That would mean a loss of at least another 3 percent of Iran’s market. China’s cutback may mean another 2-3 percent.

That would be more than 20 percent before cranking in Sri Lanka and a dozen other countries. On the other hand, some countries could pick up crude not being bought by the EU and others. The numbers are very rubbery right now. And the oil price could continue to surge—or perhaps plummet. So no conclusions are yet possible.

There is still another element to the calculation. Even before the 2012 price surge, oil prices were high and Iran’s revenues at a record level. Even if it were to lose tens of billions of dollars in oil revenues, it would still be floating on vast sums of oil income unequaled in most of its history.

And Taylor warned that Iran could force up the price of oil by “throwing a few mines in the Strait of Hormuz.”