December 31, 2021

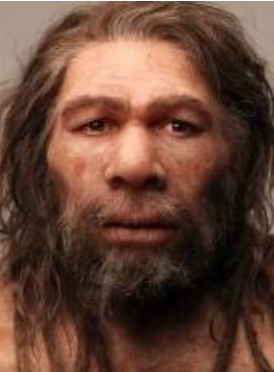

An archaeological survey has been launched in western Iran in an effort to shed new light on Neanderthal life in western Iran.

Led by Iranian archaeologists Saman Heydari-Guran and Ahmad Azadi, the survey follows up on a 2017 dig at Bawa Yawan that yielded a Neanderthal tooth that was dated as 42,000 years old.

The tooth, which belonged to a 6-year-old child, was found at a depth of 2.5 meters along with animal bones and stone tools near Kermanshah.

Heydari-Guran said, “Neanderthal extinction has been a matter of debate for many years. Discoveries, better chronologies, and genomic evidence have done much to clarify some of the issues. This evidence suggests that Neanderthals became extinct around 40,000 to 37,000 years ago, after a period of coexistence with Homo Sapiens of several millennia, involving biological and cultural interactions between the two groups.”

However, the bulk of this evidence comes from Europe and recent work in Central Asia and Siberia has shown there is considerable local variation. Southwestern Asia, despite having a number of significant Neanderthal remains, has not played a major part in the debate over extinction, according to Heydari-Guran.

In a review of the present study, Fereidoun Biglari, a Paleolithic archaeologist at the Iran National Museum, has said: “This recent discovery, along with other Neanderthal remains previously found in other parts of Zagros, including Shanidar Cave, Bisotun Cave, and Wezmeh Cave, indicate that Neanderthals were present in a wide geographical range of the Zagros from northwest to west of this mountain range since at least 80,000 until about 40,000 to 45,000 years ago when they disappeared and Homo Sapiens populations spread into the region.”

The Bawa Yawan tooth is the second Neanderthal tooth discovered in Iran. The first Neanderthal tooth was discovered in the Wezmeh cave near Kermanshah in 2001.

Moreover, the discovery of a third tooth of the Neanderthal child was announced by a joint Iranian-French team that worked in Qal-e Kord near Qazvin in 2019. These discoveries show that Iran has a rich paleoanthropological record and the country may produce important data in the future.