April 19, 2019

Former Australian Sen. Sam Dastyari has gotten divorced from his wife of eight years and headed off to South Africa where he was a contestant on an Australian television program that plunks celebrities down in the jungle and sees how they cope.

The show, “I’m a Celebrity … Get Me Out of Here,” is a copy of the old US television show, “Survivor,” but uses known public figures rather than regular folks.

Dastyari was a federal senator from the liberal Labor Party for five years until he was engulfed in scandal and forced to resign in January 2018. He has been making a living—and keeping himself in the public eye—with frequent television appearances and radio shows, in which he often makes jokes at his own expense.

However, he has admitted that he contemplated suicide after he was forced from the Senate.

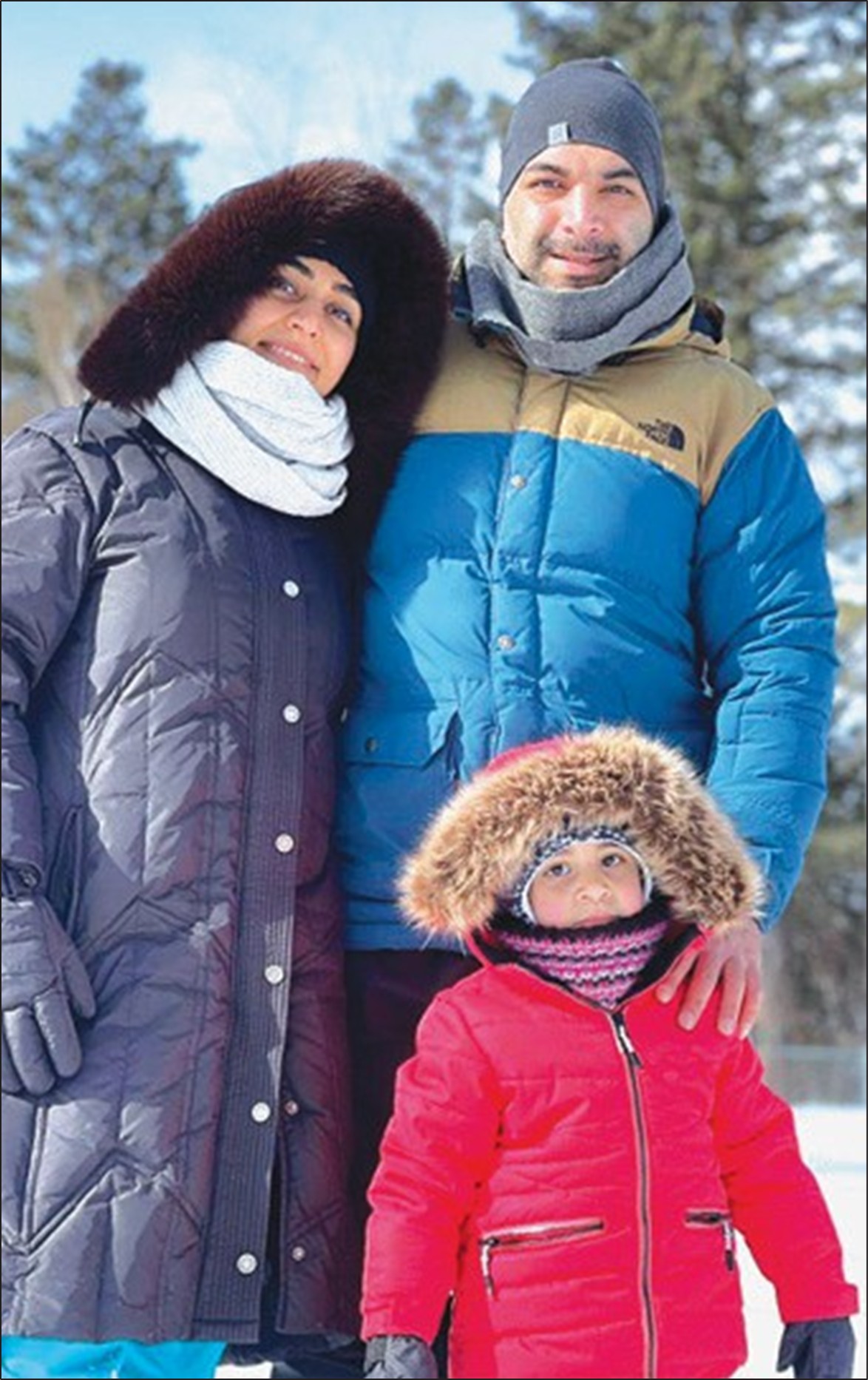

His latest personal horror was his divorce from Helen Barron, which he announced in January. Fortunately, he said it was amicable.

Dastyari, 35, broke the news from the South African jungle where he and the other contestants spent February competing on the show.

“The scandal took everything from me — my career and my family,” Dastyari told The Daily Telegraph.

“Helen stood by me during my dark period,… the days I wouldn’t leave my room when I was at rock bottom. It takes a toll on a marriage.

“Having cameras parked out the front of your house. Being followed down the streets. Not being able to read the papers because of fear of what is in them. It takes its toll,” Dastyari said.

“I changed. I broke. I know I wasn’t able to make her happy and she had a right to move on with her life. She should only ever have had to sacrifice so much. This year we did Christmas apart, sharing the kids. It hurt. It’s still raw. But Helen deserves better. She always did.”

The couple married in 2010 and Dastyari described the marriage split as “very amicable,” saying he was lucky to have “the most supportive and amazing wife.”

He said the reason he took up the televised jungle offer was for his two children.

In a video posted to social media, Dastyari said: “We do these weird things to try and make our kids like us, when in fact they are probably just going to be more embarrassed.

“In a period of time, my daughter, Hannah [now seven], will be old enough to read the Internet and read all the bad decisions I’ve made in the past,” he told The Sydney Morning Herald. “But I hope she will see the other things out there and, if that means eating a spider or lying in a snake pit, then so be it.”

Dastyari was seen in October and November attending a number of events with his new girlfriend, Claire Johnston, who worked as a media adviser to a prime minister six years ago.

Dastyari spoke of his appearance as a television contestant by saying, “Most people say shows like ‘I’m a Celebrity’ are just for washed-up actors and washed-up athletes. But I say the show can be bigger than that. I say it can be for washed-up politicians, too.”

Dastyari was born in Sari. His real first name is Sahand. He was brought to Australia by his parents, disillusioned revolutionaries, when he was four. He had a natural affinity for politics and rose very quickly through Labor Party ranks as an adult.

The former senator has said he shouldn’t have kept trying to manage relationships with donors as a senator the way he had while running the Labor Party in the state of New South Wales.

He said he never thought twice about asking a Chinese company to pay $1,670.82 worth of his travel expenses. That was the first scandal that led to his eventual departure from the Senate in disgrace.

He believes his mistake was behaving in parliament the same way he had as general secretary of the state Labor Party.

“That meant managing relationships with party donors. And that was an incredibly stupid thing to be doing,” he said in an interview last year. “I shouldn’t have been the party bagman when I was a serving Australian senator.”

He was later found promoting Chinese government policies advocated by donors, sparking complaints that he was acting like he had been bought and paid for by the Chinese regime.

Dastyari said that after initially feeling relief when he resigned, he experienced a period of depression. “I spent six days where I didn’t leave my bedroom,” he said.

“There were certainly nights where your logic goes so out the door, that you suddenly start thinking things like: ‘Well, the people who love me would be better off if I wasn’t here anymore’.”

He said, “I was out of control, and when it came crashing down, it all crashed. The hard bit there is accepting I was completely responsible for my own downfall.”

Dastyari added: “There are some things that time heals and there are some things that time doesn’t. My career is over, my marriage is over, my reputation is shattered and I have to accept that all of that is completely self-inflicted and there’s a darkness to that that knows no end.”

He said, “I’m not looking for forgiveness or acceptance from the Australian public. I just want to spend a day not hating myself so much.”

But he does want to secure some kind of future, now that the only profession he knew and was good at—politics—is history. “”I don’t know what my future holds or what I’ll be doing when I leave the jungle. If I had prospects, I probably wouldn’t be spending the next few weeks in a South African national park without a phone.”