China has banned civil servants, students and teachers in mainly Muslim Xinjiang province from fasting during Ramadan and ordered restaurants to stay open.

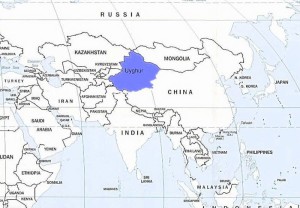

China’s ruling Communist party is officially atheist and for years has restricted Muslim practices in Xinjiang, home to the Muslim Uighur (pronounced wee-ger) minority. They total about 11 million, not even 1 percent of China’s 1.4 billion people.

“Food service workplaces will operate normal hours during Ramadan,” said a notice posted on the website of the state Food and Drug Administration in Xinjiang’s Jinghe county.

Officials in Bole county were told: “During Ramadan do not engage in fasting, vigils or other religious activities,” according to a local government website.

Each year, the authorities’ attempt to ban fasting among the Uighurs, generating widespread criticism from rights groups.

Yet in Kashgar, China’s westernmost city, close to the border with Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, Uighurs told a reporter for Al-Jazeera the restrictions have backfired. Not only have locals become more observant of Islamic practices, but many have found ways to flout Chinese laws restricting everything from who may attend the mosque to what translations of the Qoran may be read.

Uighur rights groups say China’s restrictions have added to ethnic tensions in the region, where clashes have killed hundreds in recent years.

China says it faces a “terrorist threat” in Xinjiang, with officials blaming “religious extremism” for the growing violence.

“China’s goal in prohibiting fasting is to forcibly move Uighurs away from their Muslim culture during Ramadan,” said Dilxat Rexit, a spokesman for the exiled World Uighur Congress. “Policies that prohibit religious fasting is a provocation and will only lead to instability and conflict.”

As in previous years, school children were included in directives limiting Ramadan fasting and other religious observances.

The education bureau of Tarbaghatay city, known as Tacheng in Chinese, last month ordered schools to communicate to students that “during Ramadan, ethnic minority students do not fast, do not enter mosques … and do not attend religious activities.”

Similar orders were posted on the websites of other Xinjiang education bureaus and schools.

Officials in Qiemo county last week met local religious leaders to inform them there would be increased inspections during Ramadan in order to “maintain social stability,” the county’s official website said.

Ahead of the holy month, one village in Yili, near the border with Kazakhstan, said mosques must check the identification cards of anyone who comes to pray during Ramadan, according to a notice on the government’s website.

The Bole county government said Mehmet Talip, a 90-year-old Uighur Communist Party member, had promised to avoid fasting and vowed to “not enter a mosque in order to consciously resist religious and superstitious ideas.”

The Uighurs are a Turkic ethnic group with a language and culture closer to Central Asia than China. Before the region was absorbed into the People’s Republic of China in 1949, almost everyone in Xinjiang province was Uighur.

But Uighurs are now less than half the population, as millions of Han Chinese—the majority population of China—were encouraged to settle here by the government.

That demographic shift, combined with Chinese repression, triggered a wave of violence that has left hundreds of people dead.

Last year, a suicide bomber killed 39 people in the provincial capitol of Urumqi, and police claimed to have killed 13 men who attempted to ram an explosives-laden vehicle into their office near Kashgar.

The deadly violence has sparked a massive crackdown by Beijing, with authorities announcing the convictions of more than 400 people across Xinjiang last year.

“The government says every Uighur, if they have a beard or wear a hejab, they are a terrorist,” Abdul Majid, who owns a mobile phone shop near People’s Square in Kashgar, told Al-Jazeera.

Around the corner from Kashgar’s 572-year-old Id Kah Mosque, a large notice board implores Uighurs to avoid Islamic attire. One half of the board is covered in pictures depicting traditional Uighurs—women in colorful dresses and flowing hair and clean-shaven men. The other half shows rows of men with beards and women in headscarves or face-covering veils, all with a red X over them.

In the evening, throngs of young women in headscarves or full-face veils pass signs posted at Kashgar’s main hospital reminding them veiled women cannot enter.

Along with government employees, children under the age of 18 are barred from attending mosques, yet dozens of men attending night prayers at one of Kashgar’s centuries-old mosques have brought along their children. Toddlers line up next to the adults, imitating their movements during prayers.

“Sure, it’s against the law to bring kids to the mosque, but we do it anyway,” Ghulam Abbas, a fish-seller, told Al-Jazeera.

He added that, for centuries, parents sent their children to maktaps, part-time schools at the mosque, where they memorized the Qoran—but this practice, along with most organized religious instruction, is now prohibited in Xinjiang.

Asked if Uighurs are forgetting how to recite the Qoran as a result, Abbas called his eight-year-old son over and, after some coaxing, convinced him to recite a chapter from memory. “They want to cut our children off from Islam,” Abbas said. “We are not allowed to teach them the Qoran, but we do, at home—secretly.”

The government has also barred translations of the Qoran published by Saudi Arabia and other foreigners. Only translations conducted by China’s state publishing houses are permitted.