May 26, 2018

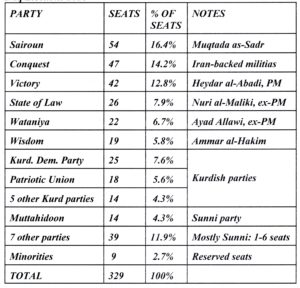

The electorate scattered their votes widely, giving 21 parties seats in the parliament.

In a further surprise, the party formed by the militias backed by Iran came in second, but with barely 14 percent of the vote. It is headed by Hadi al-Ameri, the chief of the Badr Organization, which began as an Iranian-based military group fighting Saddam in the Iran-Iraq War.

In yet another surprise, the party of Prime Minister Heydar al-Abadi, who the betting money expected to come in first, ended up in third place with just short of 13 percent.

No other party topped 10 percent.

Both Iran and the United States had men in Tehran on Election Day to try to influence the negotiating that has begun to form a government. Iran’s representative is Maj. Gen. Qasem Soleymani, the commander of the Qods Force, whose first priority is said to be to keep Sadr out of any future government. The US representative is Brett McGurk of the State Department, whose chief aim is presumably to keep the Iranian-backed militias out of the new government.

A decade ago, Sadr was a firebrand who backed Iran and sent out men to kill US soldiers among the 170,000 then occupying Iraq. He later went to Qom to polish his religious credentials. He returned to Iraq clearly soured on Iran. He has not turned friendly to the US, but has become neutral; he says he does not oppose the small force of 4,500 US troops now in Iraq primarily to train Iraqi troops. But he has made clear he wants both Iranian and American hands off Iraqi politics.

Sadr has visited Saudi Arabia and appears to fit more into the Arab nationalist fold right now. He has also made a point of condemning sectarianism. He recruited Sunnis to run on his list.

But his main thrust in the election campaign was to oppose the corruption that infects the Iraqi government. He has suggested that the parliament choose technical specialists as cabinet ministers to stop the practice of politicians in ministries handing out contracts to their buddies and relatives.

Sadr did not run for a seat and cannot become prime minister. He has not yet endorsed anyone for that post.

Fourth place in the balloting went to the party of Nuri al-Maliki, a former prime minister who pushed aside many of the military officers trained by the US and replaced them with his political favorites. When the Army collapsed under attack by the Islamic State, Maliki lost his post and was replaced by Abadi.

Fifth and sixth places went to Ayad Allawi and Ammar al-Hakim, both of whom have worked closely with the United States over the years since Saddam Hussein was toppled in 2003.

The United States presumably would like to see a governing coalition comprised of all the major parties except Maliki’s and the Iranian-backed militias, including some Kurdish parties and the largest Sunni party, Muttahidoon.

Iran is presumably starting with a core of the militias plus Maliki. But that only comes to 22.2 percent of parliament. Even if they agreed to back Abadi as prime minister, the group would only command 34.8 percent of the parliamentary votes. Iran would then need almost all the Kurdish parties to join in to command a majority. News reports in Baghdad have said that in his talks with political leaders, Soleymani has ruled out any role for Sadr and his party.

Sadr has publicly ruled out governing with either the militias or Maliki.

In sum, the election results do not look good for Iran.

There were other surprises in the election results. For example, Prime Minister Abadi’s party appealed across sectarian lines, but few expected that to work. Yet Abadi’s slate came in first in Nineveh, a majority Sunni province. It appears that voters there took a very pragmatic view, concluded that a Shiite was going to be prime minister and supported a Shiite who is unbiased and had a chance to win.

Meanwhile, in Najaf, the Qom of Iraq, voters have sent a female communist to parliament as their representative. The Communist Party, which is insignificant in Iraq, aligned itself with Sadr in this election.

The only parties overtly supporting Iran are the militia group and Maliki’s party. But Iran was not an issue discussed much during the campaign, so one cannot say that Iran has the support of less than one-quarter of the population. It may have more or, more likely, less.

Furthermore, the turnout for the election was very poor, suggesting the public is disgusted with the political establishment. Sadr’s party ran against the political establishment, so its success further emphasizes public disgust. The turnout this year was only 44 percent, whereas 60 percent voted in the 2014 balloting and 80 percent in first post-Saddam vote in 2005.