December 20-2013

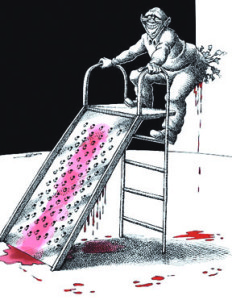

Iran’s secret nuclear ambitions enjoy widespread approval among Iranians who don’t approve of the clerical dictatorship that has ruled them for the past 30 years.

Polling conducted by the U.S. firm Zogby Research Services indicated that while roughly half the people support the regime, two-thirds of them want Iran to acquire nuclear weapons. And a staggering 96 percent said acquiring nukes is worth the price of “economic sanctions and international isolation.”

Still more surprising, only 5 percent say that “improving relations with the United States and the West in general” should be a foreign policy priority.

Lifting Western economic and financial sanctions against Iran for its covert work on achieving nuclear weapons capability was ranked a priority by only 7 percent of respondents.

So what issues do Iranians say belong among top priorities?

— Unemployment 29 percent.

— Advancing democracy 24 percent.

— Protecting personal and civil rights 23 percent

— Ending corruption and the need for political reform 36 percent.

— Increasing the rights women 19 percent.

There is clearly a national consensus in favor of acquiring nuclear weapons, which is understandable when one looks at the strategic map of the world as seen from Tehran: Six of the world’s nine nuclear powers surround Iran — Israel to the west, Russia to the north, China to the northeast, Pakistan and India to the East and the U.S. Navy’s 5th Fleet to the south.

The late Shah of Iran, deposed by the 1979 clerical-led revolution (the mullahs’ vast land holdings had been nationalized by the shah for redistribution among the poor), decided as early as 1972 that Iran had to become a nuclear power.

In 1968, British Prime Minister Harold Wilson abandoned all of Britain’s security commitments “east of Suez,” from the Suez Canal to Singapore. The biggest slice of that commitment was the Persian Gulf and its vast oil supplies.

Following the British decision, Mohammad-Reza Shah Pahlavi stepped into the vacuum. With the blessings of the “Nixon Doctrine,” Iran became the “guardian” of the gulf’s vast oil reserves on behalf of Western security interests.

The shah ordered billions of dollars worth of military equipment, including giant hovercraft and seven Boeing 707s, for Iran’s new Persian Gulf security strategy. The plan called for an Iranian military riposte in less than half a day against any coup attempt in the oil sheikhdoms on the western side of the gulf, from Kuwait to Oman.

The fear in the 1970s was of a pro-Soviet or pro-Iraq coup in a small sheikhdom that might prove contagious up and down the Arab side of the gulf. In 1990, Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait, triggering the first Gulf War and his defeat.

Oman was already under attack — known as the Dhofar Rebellion — from South Yemen’s freshly minted Marxist regime under the personal control of Markus Wolf, then head of the East German intelligence service, presumably assigned by his KGB superiors.

The shah told this reporter off the record in 1973 he was determined Iran become a nuclear power to deter would-be adversaries. The only ones he could see then were the Soviet Union and its East European satellites and their close relations with Saddam Hussein’s Iraq.

We first covered Iran in the 1953 upheaval when a military coup, aided and abetted by the CIA, overthrew the increasingly anti-Western and pro-Soviet Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh, who was trying to reduce the shah to a figurehead monarch.

Iran’s Tudeh party, secretly headquartered in East Berlin, was then in a covert alliance with Mossadegh.

Everything about today’s Iran is complex. The latest public opinion poll conducted by Zogby demonstrates how many assumptions about Iranian public opinion were dangerously off the mark.

Soon to enter its third year with some 125,000 killed, Syria’s civil war shows organizations allied with al-Qaida steadily gaining ground at the expense of pro-Western groups. The top anti-Assad commanding general, Salim Idris, took flight as he no longer trusted some of the officers on his staff.

If this trend continues it will be Syrian President Bashar Assad and his still-loyal army against an enemy dominated by Islamist extremist followers of al-Qaida. This will inevitably weaken the case of Western powers that originally backed those trying to overthrow Assad, a close ally of Iran.

What little aid the United States managed to funnel to anti-Assad forces was stopped as its trickle of non-lethal supplies was falling to Islamist units.

U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry’s plan to get Assad to hand over power to a transitional government was beginning to look increasingly irrelevant.

Neither Russia nor the Obama administration nor their respective friends and allies want to see Syria became a global center for jihadi terrorists.

Nerves were on edge in most European capitals. Many of their own naturalized Arab citizens had joined the ranks of pro-al-Qaida fighters in Syria.

The number Syrian refugees fleeing the civil war was already staggering — 800,000 in Lebanon (Lebanese authorities say it’s closer to 1.2 million, or one-quarter of its population); 250,000 in impoverished Jordan; thousands of wealthy Syrians wound up in Turkey and the rest of Europe.

It was the influx of Palestinian refugees from Jordan (where they had been defeated in a civil war against the late King Hussein’s army) that triggered a 15-year-long Lebanese civil war (1975-1990).

One key player who doesn’t seem overly concerned about staying firmly anchored in the anti-Assad camp was Saudi Arabia. Its main concern is Iran and its growing influence in the Persian Gulf.

The Saudi leadership appears to be far more worried about what will be seen as a victory for Iran if Assad prevails than it is about a victory for Islamist extremists.

Other players see Assad’s regime in Damascus as the lesser of several evils. By the time the Syrian peace conference convenes Jan. 22 in Montreux on Lake Geneva, this may become the new consensus.

This wouldn’t be a happy prospect for Kerry’s now urgent mission to midwife a peaceful settlement that would spawn a new nation of Palestine in the West Bank.

Arnaud de Borchgrave, a former president and chief executive officer at United Press International, contributes commentaries as UPI editor at large.