No explanation was given for the long delay or for the shift from lopping off three zeros to four.

The constantly shifting policies make the regime look disordered and inept, unable to make decisions or to stick with them once they are made.

On Sunday, Central Bank Governor Mahmud Bahmani said Iran plans to slash four zeros from its national currency in “one to two years,” seeking parity with the US dollar.

But five days earlier, Bahmani said four zeros would be sliced off under a plan to be presented to the cabinet “within the next six months.” Now six months has become 12 to 24 months.

And three days before Bahmani said four zeros would go, Finance Minister Shams-eddin Hossaini said three zeros would be lopped off. And he said that would happen during the current Persian year.

In September 2009, Bah-mani announced that after long study the Central Bank had decided to recommend that three zeros be removed from the rial. In January 2010, President Ahmadi-nejad announced his approval of the three-zero reduction.

Now Bahmani has suddenly added a zero. While he gave no explanation for the change, he hinted that he was seeking parity with the dollar.

“The new rial … will be equal in value to one (US) dollar,” the state news agency quoted Bahmani as saying, adding that it would take “one to two years” to be implemented.

Bahmani did not indicate whether the authorities would try to maintain a fixed parity between the greenback and the Iranian currency following the zero reduction.

Bahmani failed to say why Iran would want the rial to have parity with a currency the Islamic Republic says is dying and is rapidly being rejected by the rest of the world. Three years ago, Ahmadi-nejad ordered all government agencies to calculate foreign exchange requirements in terms of the euro. But Ahmadi-nejad’s own budget continues to use dollar conversions and only a handful of government agencies state foreign exchange in terms of the euro.

Ahmadi-nejad once led a vocal campaign against the dollar, calling it a weak currency. Perhaps not coincidentally, that was when the US Treasury had started its campaign to limit Iran’s ability to conduct transactions in the dollar. Like many of Ahmadi-nejad’s vocal campaigns, his anti-dollar diatribes have long since faded and been replaced by other rhetorical frenzies.

The government has been talking about changing the national currency to get rid of the voluminous zeros ever since 2007 without ever actually doing anything about it.

The problem is that one rial will buy nothing. One rial is currently worth a tad more than 1/100th of a US cent. It takes 105 rials to make a single US penny.

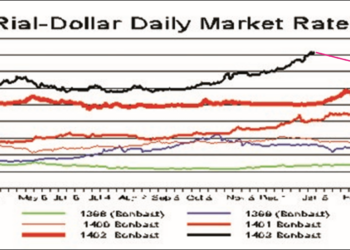

The rial has dropped drastically since the Islamic revolution, from 70 to the dollar in 1979, to around 10,500 today.

Bahmani said Sunday that the name of the new currency would not change, but presumably he could change his mind about that just as he changed his mind about the number of zeros to be lopped off.

Bahmani also said the new rial would be “introduced gradually so that people can get used to It.” He didn’t explain what that meant. Normally, countries introduce currency shifts over a period of a few weeks to a few months, with the new currency appearing in banks one day, shops told to change their posted rates some days later and the old currency declared invalid later on.

Bahmani said, “Some people think removing the zeros will weaken the national currency … but it will instead cut inflation. Removing four zeros will also facilitate trade.” But lopping off zeros is purely cosmetic and has nothing at all to do with inflation. The main benefit of such a change is convenience. The public is no longer dealing with immense figures—millions, billions and trillions. A $100,000 house in Tehran is worth 1 billion rials.

If the rial indeed is configured to be close to a dollar, Iran will likely resurrect the dinar. The rial is officially divided into 100 dinars, but the dinar is now a relic recalled only by the very aged. The dinar effectively died with the gross inflation of World War II.

The rial was introduced in 1798 by the new Qajar Dynasty. In 1825, the Qajars changed the name to gheran. In 1932, the Pahlavi Dynasty switched from the gheran back to the rial, with the rial worth about 10 US cents of the day and divided into 100 dinars.

The Pahlavi rial slipped in value from about 10 to the dollar in 1932 to 70 to the dollar by the late 1950s. It then remained very stable—one of the world’s most stable currencies for two decades—until the 1979 revolution when it went into a sharp plunge. The Central Bank’s posted price for the rial on Monday was 10,401 to the US dollar.

The term rial (in various spellings) is currently used for the currencies of Brazil, Cambodia, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Oman and Qatar.

Many countries shift the name of their currency when they lop off zeros and present the new currency as the end of inflation. Inflation, however, results from government policies, not the name of a currency.