February 18, 2022

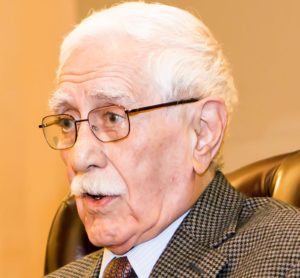

Iraj Pezeshkzad, whose bestselling comic novel, “My Uncle Napoleon,” lampooned Persian culture’s self-aggrandizing and paranoid behavior as the country entered the modern era, has died in California. He was 94.

The travails of Uncle Napoleon, whose delusions have him seeing Britain’s hand in the troubles plaguing the waning days of his aristocratic family during World War II, became one of the most-beloved television serials ever in Iran when it aired in 1976.

The fervor of the 1979 Islamic Revolution saw the book banned and the series never aired again on Iranian state television. Pezeshkzad himself would ultimately land in Los Angeles, part of an emigre society of Iranians still there that see the California city jokingly referred to as “Tehrangeles” even today.

Pezeshkzad’s words and turns of phrase from the novel still litter Iranian culture, including raunchy references to “San Francisco” as an innuendo for sexual liaisons. The same goes for passages about the power of love, as described in one scene by Uncle Napoleon’s long-suffering servant, Mash Ghasem.

“When you don’t see her, it’s like your heart is frozen,” says the servant, portrayed in a softly-lit basement scene in the series by actor Parviz Fannizadeh. “When you see her, it’s like a bakery oven is lit in your heart.”

Iranian state media did not report on his death, though the British ambassador to Iran offered his sympathy. (A former British ambassador once commented that Tehran was a great diplomatic post for a Briton because it was the only capital in the world where the public still believed thet Britain had real power.)

“Although the book is not political, it is politically subversive, targeting a certain mentality and attitude,” wrote author Azar Nafisi in 2006. “Its protagonist is a small-minded and incompetent personality who blames his failures and his own insignificance on an all-powerful entity, thereby making himself significant and indispensable.

“In Iran, for example, as Pezeshkzad has mentioned elsewhere, this attitude is not limited to ‘common’ people, but is in fact more prevalent among the so-called political and intellectual elite.”

That’s something Pezeshk-zad said existed even in his family.

“When I was learning to talk, the words that I heard after bread, water, meat and so on were, ‘Yes, it’s the work of the British,” he told a 2009 BBC documentary.

“By the time I wrote this novel, everyone had pretty much realized that British imperialism with all its power and greatness had withered away,” he told the BBC. “However, I had underestimated this phobia and, especially after the revolution, I realized it was and still is extremely strong.”

He described having people praise him for seeing the British hand in everything the exact opposite of what he tried to say in his novel.