May 12, 2023

Neckties are making a slow but noticeable return in Tehran, as men no longer view the regime as legitimately able to dictate their clothing for ideological reasons.

Iran effectively banned the tie after the 1979 revolution by portraying it as a Western affectation, or, worse, a sign of subservience to Western powers. Although it has made a slow comeback since, with an acceleration recently, government officials and most Iranian men continue to shun the cravat.

The upmarket Zagros shop on the capital’s Nelson Mandela Boulevard, however, displays rows of ties in different colors and in wool, cotton and silk.

“We sell around 100 a month,” said deputy store manager Mohammad Arjmand, 35. “We import them mostly from Turkey, but some are also made in Iran.

“Customers buy them for ceremonies or for work. In this neighborhood, you will find that two out of 10 people wear one. These days more people are wearing ties compared with previous decades.”

The recent unrest “had no effect on our sales”, said branch manager Ali Fattahi, 38. “Our customers who were wearing ties before still do so and come to us regularly to buy new ones.”

Iran’s Shiite clerics who came to power in 1979 banned the tie because, in their eyes, it was un-Islamic, a sign of decadence, a symbol of the Christian cross and the quintessence of Western dress imposed by the Shah, one trader, who asked not to be identified, told Agence France Presse.

After vanishing for decades, ties reappeared in some shop windows during the era of Reformist President Mohammad Khatami from 1997 to 2005.

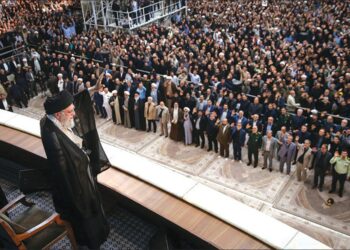

Today, government ministers, senior civil servants and heads of state-owned companies don’t wear ties with their suits and opt for shirts with buttoned, open or Mao collars.

Lawyer Masud Molapanah said, “Wearing a tie is certainly not a crime” under the constitution or Islamic Sharia law. “And there are dress restrictions in certain places such as on television.”

Mohammad Javad, while choosing a tie, was accompanied by his chador-clad mother, who not only encourages him to wear one, but also asked the salesmen to teach her how to tie it properly for her son.

“At one time, some sought to remove it,” said the 50-year-old state employee, with a smile. “The reason given was the rejection of any sign of Westernization.

“But then it would have been necessary to also remove the suit and return to the traditional dress worn at the time of the Qajar Dynasty” of 1794-1925, his mother said, commenting that this “was obviously impossible.”

The head of a nearby Pierre Cardin store, Mehran Sharifi, 35, said many young people now are enthusiastic about the necktie.

“Ties give prestige to people—a lot of people buy them,” said this son and grandson of a tailor, pointing to a century-old photograph on the wall of his grandfather wearing a tie.

“Customers come to buy suits and we match ties to their choice of clothing. Others buy them as a gift.”

In some classy cafes, the black tie or bowtie are part of the uniform of waiters, and doctors in several Tehran districts have also sported ties.

The fashion accessory is almost compulsory for Iranians working at embassies and in some foreign companies, although most remove their ties when they go out on the street.

Sadeq, 39, employed at the Japanese embassy, said he puts on his tie when he gets to work “because wearing a tie in public is not very common in Iran.”

“If you dress up like that and walk in the street, you’ll definitely turn a few heads. People will think you’re either a foreigner or someone headed to a very formal meeting with foreigners.”