December 13-2013

This is the first of three-part article.

By Jahangir Amuzegar

Of the six politicians who served as president of the Islamic Republic between 1979 and 2013, none has been so mercilessly vilified by a multitude of his detractors, or so admiringly praised by his worshipful friends and acolytes, as Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. There is also no doubt that he has been both patriotic and well-meaning.

What he did to the country and the economy clearly reflected the best of his knowledge and intentions. He was a true supporter of the poor and underprivileged.

Yet his decisions and actions damaged the Iranian polity, society, and economy more than those of any other leader of the Islamic Republic.

A self-made man from a large working- class family with brief civil service as a provincial governor and a controversial This darkest of all dark horses managed to win another term in 2009, defeating a former wartime prime minister and a former speaker of the Majlis. The second victory, however, was marred by widespread accusations of vote-rigging and fraud. Massive street demonstrations protesting his election resulted in bloodshed, incarceration of peaceful protesters and the house arrest of his two main rivals. Facing this havoc, he still struck an arrogant, defiant and combative attitude, calling the protesters ‘weeds and debris.’ His second term also turned out to be crisis-ridden as he tangled openly with the Majlis speaker and the judiciary chief, was overridden by the supreme leader on several occasions, and steadily lost the full support of conservative Majlis deputies and hard-line newspapers.

As it ultimately turned out, he was be the wrong man for the job. He lacked the proper dignity and maturity to handle his position, mismanaged the country’s delicate and vulnerable economy, and adopted a needlessly belligerent and defiant position toward the West.

PERSONAL VALUES

As a product of hard-scrabble roots and a self-styled crusader for the poor and the disenfranchised, Ahmadinejad perceived economics as a handbook for distributing assets and income rather than primarily a source of income and wealth creation. A pious Muslim, he rejected all non-Islamic economic systems Ñ capitalism, socialism and communism Ñ as unjust, exploitative and oppressive. Consequently, he found the current personal and regional distribution of wealth and income in the global as well as the Iranian economy unfair, unjust and distorted. He also harbored an irrational personal and ideological grudge against banks and bankers, wishing to abolish interest payments and encourage non-interest banking institutions (Qarzol-Hassaneh). He distrusted big business, favoring small production units.

He regarded inflation a result of higher production costs rather than a monetary phenomenon. Believing money to be the answer to every social and economic problem, he undertook an unprecedented expansionary monetary policy. He believed that the reform and reconstruction measures undertaken by his two predecessors had benefited some privileged segments of society and bypassed the masses. In particular, he thought that the oil money had been unjustly distributed. An ardent Iranian chauvinist and an Islamic zealot, he believed that the West’s Ògeopolitical hegemony’ (called ‘arrogance’ in the Islamic Republic’s lexicon) has to be challenged for both political and religious reasons.

Having caused a sea change in Iranian politics by besting four better-known, more experienced, more attractive, more qualified and more promising contenders, he was naturally expected to show a certain humility and to exhibit respect for the defeated elders and a willingness to consult with them. Instead, he took a defi- ant, condescending and dismissive attitude, repeatedly bragging about his more than 20 million votes and claiming to have a mandate for drastic change.

MANAGEMENT STYLE

As a political neophyte with little managerial knowledge or experience but a huge ego and unbounded self-confidence, he confronted his formidable presidential tasks with a naive abandon. He adopted an informal, down-to-earth manner but micromanaged behavior, often in clear violation of statutory requirements. Convening cabinet meetings periodically in all of the country’s 31 ostans (provinces), making hundreds of personal trips to different cities, answering millions of petitions from the rank and file, approving thousands of small development projects on the spot during his provincial trips exemplify his populist style.

Arbitrary selection of staff and bureaucratic cadres was another hallmark of his administration. Instead of considering expertise, experience and professional qualifications as criteria for choosing the government’s top officers, he chose professional affinity, personal loyalty and total obedience. True to form, he methodically dismissed the technocrats assembled by his two predecessors and replaced them by commanders from the Islamic Revolution Guard Corp (IRGC) and the Basij militia. At one time, 12 of his 18-member cabinet were from these two organizations; and when his administration ended, six ministers were still former military and security officers. By one estimate, the share of the IRGC in the economy increased 10 times during his tenure.

Adulation was his second major criterion for personnel selection. For example, a mid-level functionary who described him as ‘the third century’s miracle-maker,’ and his maskan-e-mehr housing project as ‘the finest undertaking since Adam,’ 1 was promoted to first vice president. A director of Iran’s Tourist Organization who called him ‘Iran’s golden opportunity,’ whose ‘audacity has now become universally recognized’2 became his chief of staff and number-one adviser. A professor in one of Iran’s third-rate universities was made a cabinet minister, as he had supervised the president’s doctoral thesis on traffic management.

Ahmadinejad’s dictatorial tendencies were another hallmark of his eight-year administration. Unquestioned acceptance of his decisions and faithful execution of his orders were prerequisites for holding major state positions. Failure resulted in quick dismissal. 3 A score of administrative and economic councils in charge of auxiliary decision making were dismembered in the first few months of his administration.

And, most significantly, the Planning and Budget Organization, the purveyor of Iran’s five-year development plans and preparation of fiscal budgets, was abolished and its duties transferred to the president’s office.

Issuing ministerial decrees contrary to established Majlis statutes, refusing to execute legislation, hasty and ad hoc decisions with no prior preparation (e.g., approving some100 small projects in two 126 hours on one of his provincial trips) and other such actions demonstrate his governing

style.4 One of his dismissed cabinet ministers describes him as an egotist who

dismisses his critics, feels answerable to no one, places blame on others and belittles everyone around him.

He and his disciples have frequently bragged about his international reputation.

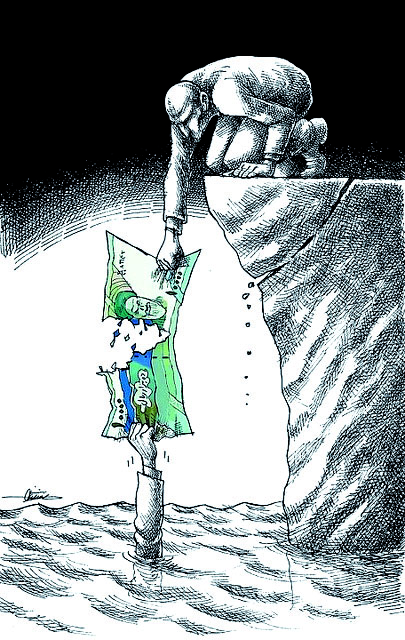

One of his ardent devotees has called him ‘a unique and incomparable global leader.’ 5 He himself once said about his trips to various countries, ‘Everyone is eager to hear the Iranian people’s message. The world is rapidly becoming Ahmadinejadized.’ 6 In a sense, no head of a government of the size and significance of Iran has been so well-known and talked about around the globe. He was the butt of jokes on late-night American comedy shows and a gift from heaven to cartoonists.

ECONOMIC APPROACH

With the exception of Ahmadinejad himself and his small circle of friends and admirers, there is no analyst inside or outside of Iran who does not believe that the Iranian economy was grossly mismanaged, if not permanently damaged, during his administration. The extent and dimensions of this mismanagement, however, are hard to assess due to the official data that is deliberately withheld, camouflaged, doctored, falsified or contradicted by the agencies involved.7 A recent report by the Majlis’ Research Center refers to most of the 2005-13 official data as defective and misleading.8 A Majlis deputy has asked for an independent governmental commission to review all data presented by the administration. 9

After publishing cryptic and questionable data on basic economic indicators in his first term, the administration stopped some100 small projects in two releasing figures in 2008 on national income (GDP growth). Figures on inflation and unemployment released by the Central Bank and the Statistical Center have been contradictory and dubious.

Figures on foreign-exchange reserves are labeled ‘confidential’ and not published.

Budget deficits are routinely camouflaged by counting borrowing as revenue. Due to these shortcomings, all arguments and conclusions made here must be treated with caution and subject to necessary correction. Ahmadinejad’s eight-year economic record may be said to represent the soul of his presidency.

He began his tenure with lofty rhetoric. Slave to unnecessary details, the new president initially announced four transcendental values, fourteen basic objectives, and 58 specific proposals to improve the Iranian economy, the main popular concern.10 True to his campaign promises, these values included justice, empathy, service to people, and improvements in the country’s material and spiritual conditions. The main objectives, however, included essentially justice: fighting against poverty, corruption, discrimination and nepotism; progressing toward an Islamic society; and observing justice, peace and dignity in international relations.

His repeated slogans of ‘justice, compassion, fairness and integrity’ promising fair income and wealth distribution, increasing economic opportunities, and fighting corruption were welcome by a large segment of the population. Passing as a champion of the poor and working classes, he called himself the people’s ‘servant’ (nokar) and defender of the ‘oppressed’ (mazloom); both words signify a humbler and sharper connotation in Persian.

Amuzegar served the prerevolutionary government of Iran as minister of commerce, minister of finance and ambassador-at-large. He was on the Executive Board of the International Monetary Fund, representing Iran and several other member countries between 1974 and 1980. He has taught at UCLA, the University of Michigan, Michigan State University, the University of Maryland, American University and Johns Hopkins SAIS. He is the author of seven books and more than 100 articles on Iran, oil, OPEC and economic development.