The book tells the story of how Nazanin Afshin-Jam worked to achieve freedom for Nazanin Fatehi, a poor teenaged girl sentenced to die for stabbing to death the man who was in the process of trying to rape her.

To the amazement of many, Afshin-Jam’s campaign to free the other Nazanin worked. The teenager was freed in January 2007.

Afshin-Jam then organized a human rights organization, Stop Child Executions, to try to raise awareness of other such threatened executions of teens.

But Afshin-Jam reveals a dark side to her effort to free the other Nazanin. Nazanin Fatehi has disappeared.

“It’s the biggest mystery,” she says. “The last time we spoke, she said she had met someone. I want to think that somebody swept her off her feet and said, ‘Let’s get away from all this.’

“But the more realistic side of me thinks that maybe she was harassed by the regime,” Afshin-Jam says. She confesses that her biggest fear is that the other Nazanin fell victim to retribution from the family of the man she killed.

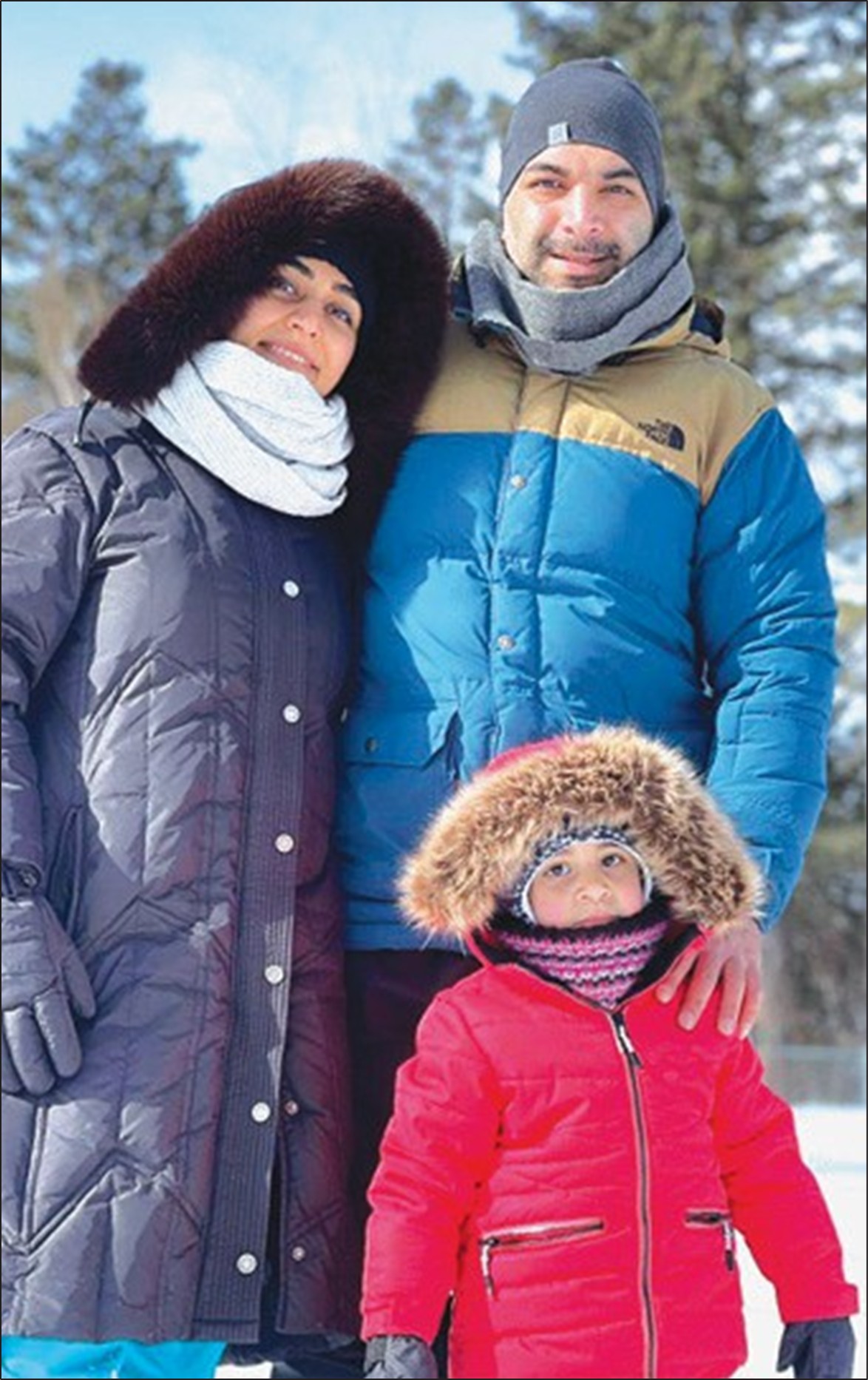

Afshin-Jam is now Nazanin Afshin-Jam MacKay, wife of the defense minister of Canada and a woman who is now known from Newfoundland to the Yukon. (That’s Canadian for from Maine to California.)

The Globe and Mail, Canada’s main national daily, says Afshin-Jam was courted by both of the main Canadian parties, the Liberals and Conservatives. She seemed like an ideal candidate—smart, beautiful, able to speak clearly. But she turned down both parties. “I wanted to remain apolitical,” she explains.

That may be just a tad tougher now that she has married a man most Canadians expect will eventually seek to become the leader of the Conservative Party and a future prime minister of Canada.

Her campaign to overturn the death sentence is the core subject of “The Tale of Two Nazanins,” a book written with Toronto journalist Susan McClelland and published by Harper Collins of Canada. Afshin-Jam worked on the book while completing an online master’s degree in diplomacy at Norwich University in Vermont.

Her new husband is mentioned only on the last page, so Canadian political junkies won’t get much fodder from this book.

The story shifts between Afshin-Jam’s privileged life in Canada and Fatehi’s plight as a 17-year-old stuck in a jail cell.

The Globe and Mail comments: “There is an underlying theme in the book that, but for her family’s escape from Iran, Ms. Afshin-Jam might have found herself in a similar place, certainly forced to obey the rules of a society that, she says, treats ‘a woman’s life as equal to half a man’s.’”

Their circumstances were very different, however. Fatehi comes from a poor Kurdish family with a rigid, traditional patriarch, while Afshin-Jam’s family was educated and liberal-minded. Her grandfather, a judge and former general, later found himself on the wrong side of rising conservative forces in the country. He encouraged his daughter, Jalel, Nazanin’s mother, to choose her own religion after she stumbled on a Bible in his library. Eventually, Jalel converted from Islam, so Afshin-Jam and her sister grew up as Catholics.

In the book, Ms. Afshin-Jam recounts the day she first saw the scars on her father’s back, where he had been whipped before fleeing Iran. In 1979, while manager of the Tehran Sheraton Hotel, he was beaten and taken into custody by the Pasdaran, who accused him of playing prohibited music and allowing men and women to mingle at the hotel. He eventually secured a temporary release and escaped with his family to Spain. A year later, the family settled in Vancouver.

As a teenager, Nazanin joined the air cadets, rising to the highest rank, and earning her pilot’s license at age 16. “You are seeing me right now – I am wearing lipstick and I’m very girly – but I have this other side to me. In the cadets, I was doing survival exercises with dirt on my face, living out in the bush for days on my own.”

She realized that celebrity status helps a person accomplish other things. She began to enter beauty contest, won Miss Canada World and then was runner-up in the 2003 global Miss World contest.

She then started a singing career with a seductive video for her first single. ”I wanted another platform to speak on my issues,” she told the Globe and Mail. “But you can’t be creative, when your mind is focused on something else.”

The singing career is now history.

She explains how people listen more to sports stars and celebrities. Back then, she was working as a Red Cross youth educator, “reaching 30 people at a time.” The Miss World title prompted people to take her calls, and sign her global petition, when she began fighting for the other Nazanin.

The Canadian Nazanin learned about the other Nazanin in an e-mail she received after the Miss World pageant. After the Iranian Nazanin was freed in January 2007, Afshin-Jam tackled other human-rights abuses in Iran. That was when she met Peter MacKay, then foreign affairs minister.

In a meeting in his Ottawa office, he gave her his card. She used the contact a few months later to help another teenager at risk of execution, and he raised the cases later with political representatives in Iran. They stayed in touch, went for dinner after she moved to Ottawa to continue her advocacy work, and soon were dating.

Last year, MacKay proposed during a cycling trip to Valentia Island in Ireland, homeland of his mother’s family. “He was very poetic,” she says. “It was very romantic.”

The couple now split their time between Ottawa, the capital of Canada, and New Glasgow, Nova Scotia, his home town and the center of his parliamentary constituency or riding, to use the Canadian term.

She tells the Globe and Mail they don’t agree on everything. Asked for an example, she laughs and says, “I’m not going to go there.”

Starting a family is not in a subject in dispute. Her mother leads the campaign for grandchildren. “She called this morning!” Afshin-Jam says. “If it was up to her, I’d just be married, have kids, have a quote-unquote normal life. She thinks that’s happiness. But she doesn’t understand happiness for me means something different. I often have those conversations with her. Repeatedly.”