It is a problem that legions of Iranian immigrants in Canada have complained about. Much blame goes to the fact that the licensing boards are run by the provinces, not the federal government, and the boards are often dominated by members of the profession who seem to dislike licensing foreigners.

Canadian Immigration Minister Jason Kenney last week announced plans to hire an outside company to assess the educational credentials of newcomers before they arrive in Canada.

Kenney said the government will ask for bids within the next two months in the hopes of selecting a non-governmental organization that can begin conducting these assessments overseas by the end of the year.

“The overall goal here is to better select and better support potential immigrants before they come to Canada so they can hit the ground running once they arrive by integrating quickly into our labor market,” he said last Wednesday.

“Once this process is in place, we think this will result in a significant improvement in the ‘points grid’ system we use to assess applicants to the foreign skilled worker program.”

Unlike the United States, Canada uses a ‘point’ system to rank applicants for immigration visas. More education wins more points. Fluency in English and French earns further points. A willingness to live outside the popular abodes of Montreal, Toronto and Vancouver wins even more points.

Kenney said the idea is to “be more up front and honest” with would-be newcomers by giving them a sense of how their credentials stack up against someone with a similar Canadian education. It would also help screen out those without adequate levels of education.

In other words, simply having a degree in a particular field will no longer be enough to garner points toward acceptance as a skilled worker.

The pre-arrival assessment, however, does not guarantee applicants will become licensed in their field. That licensing power will still lie with the professional boards in the provinces. And that, Kenney suggested, is another problem.

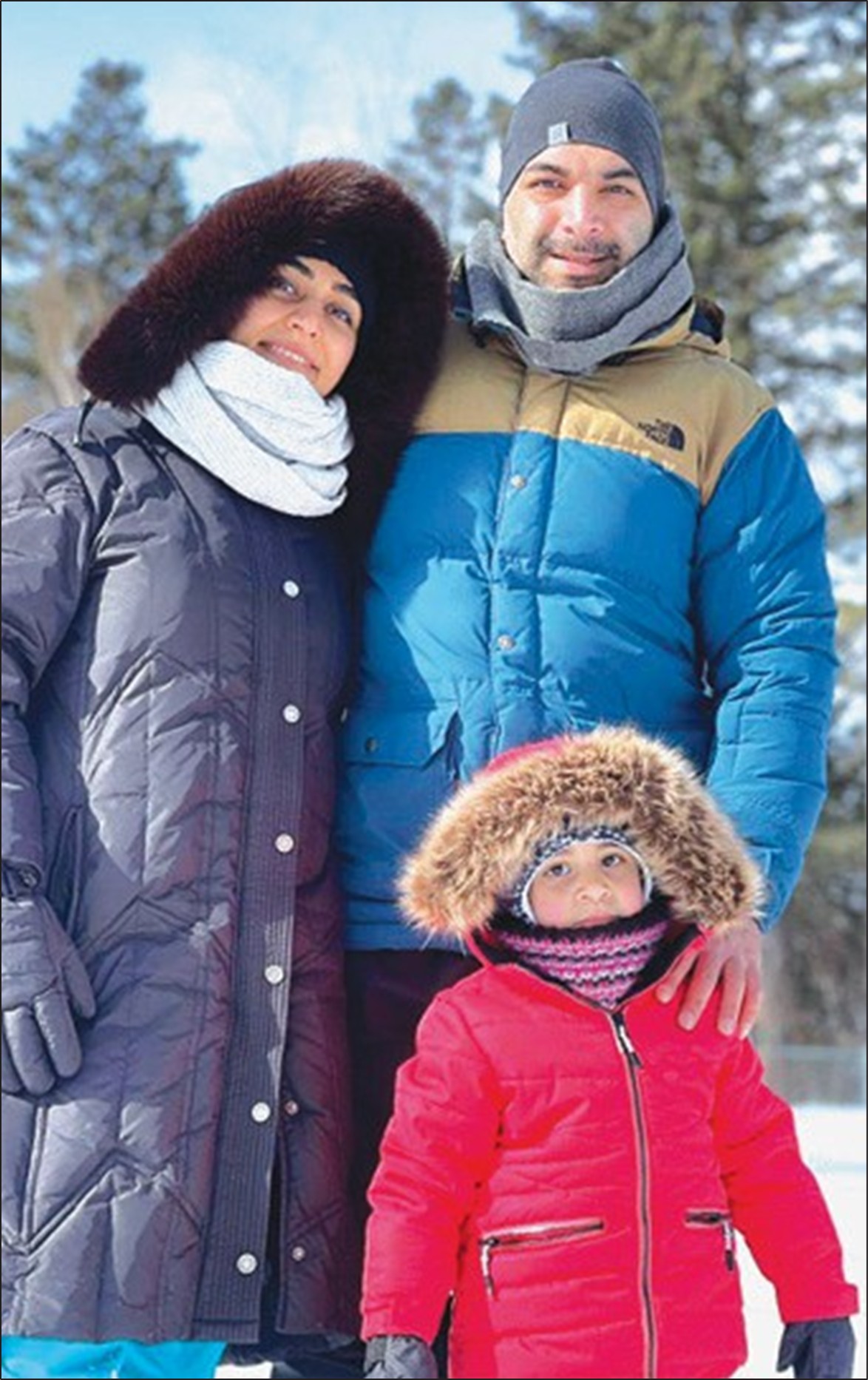

Kenney cited the case of an Iranian couple—a radiologist and orthopedic surgeon—who have struggled to get their skills recognized and have now resolved to return to Iran.

He suggested some regulatory bodies have been overly protectionist and ought to “do a lot more” to streamline their processes.

The opposition immigration critic in Parliament, Don Davies, called Kenney’s idea a good start, but complained it still doesn’t do anything to actually get a person’s credentials recognized in Canada.

Davies agreed the provinces—and particularly the licensing boards—have put up barriers, for instance, to protect their members’ earnings potential, but suggested there are ways the federal government can get around it that Kenney is not trying.

Davies has previously urged the federal government to enter into “nation-to-nation treaty discussions” to mutually recognize certain credentials, for example, from a particular university.

That, however, would be unlikely to help Iranians since relations between Canada and Iran are frozen at a low level that doesn’t allow the option of such negotiations.