who appears to face imminent execution in the Islamic Republic.

Malekpour was living in Canada and on his way to citizenship when he retuned home to visit his dying father in 2008. He was soon arrested and accused of master-minding pornographic websites. He was sentenced to die in 2010. Last week, his lawyers reported that his case file had been sent to the office that schedules executions.

That set off bells in Canada and prompted officials to speak out.

The spokesman for the Foreign Affairs Department said, “Canada condemns Iran’s reported decision to execute Mr. Malekpour. We hold Iran accountable for his treatment and well-being.”

That was followed by the unanimous approval of the resolution on Malekpour by the House of Commons.

That resolution called on Iran to “reverse its current course, meet its international human rights obligations and release prisoners such as Saeed Malekpour and others who have failed to receive fair and transparent legal treatment.”

Malekpour’s family says he has had nothing to do with any pornographic sites. They say Malekpour developed software for easy loading of photographs onto websites and that some pornographic sites subsequently used that software, which bears his name as the developer.

The Toronto Star’s Olivia Ward looked into Malekpour’s history. She said, “For most of his 36 years, Malekpour was a problem-solver, a man with a workaround mind. His family’s troubleshooter. The cleverest in his class.…

“Malekpour is living in an Iranian Kafka novel from which there is no exit.

To his family, it is an unimaginable fate for an eldest son who could fix everything from toys and electrical gadgets to hurt feelings and family feuds. Who bore the burden when his middle-aged father’s health declined, and who became the nominal head of the family of four while still too young to start his own.”

She said he got a job in Iran’s biggest car plant and used his earnings to helped pay his siblings’ university fees.

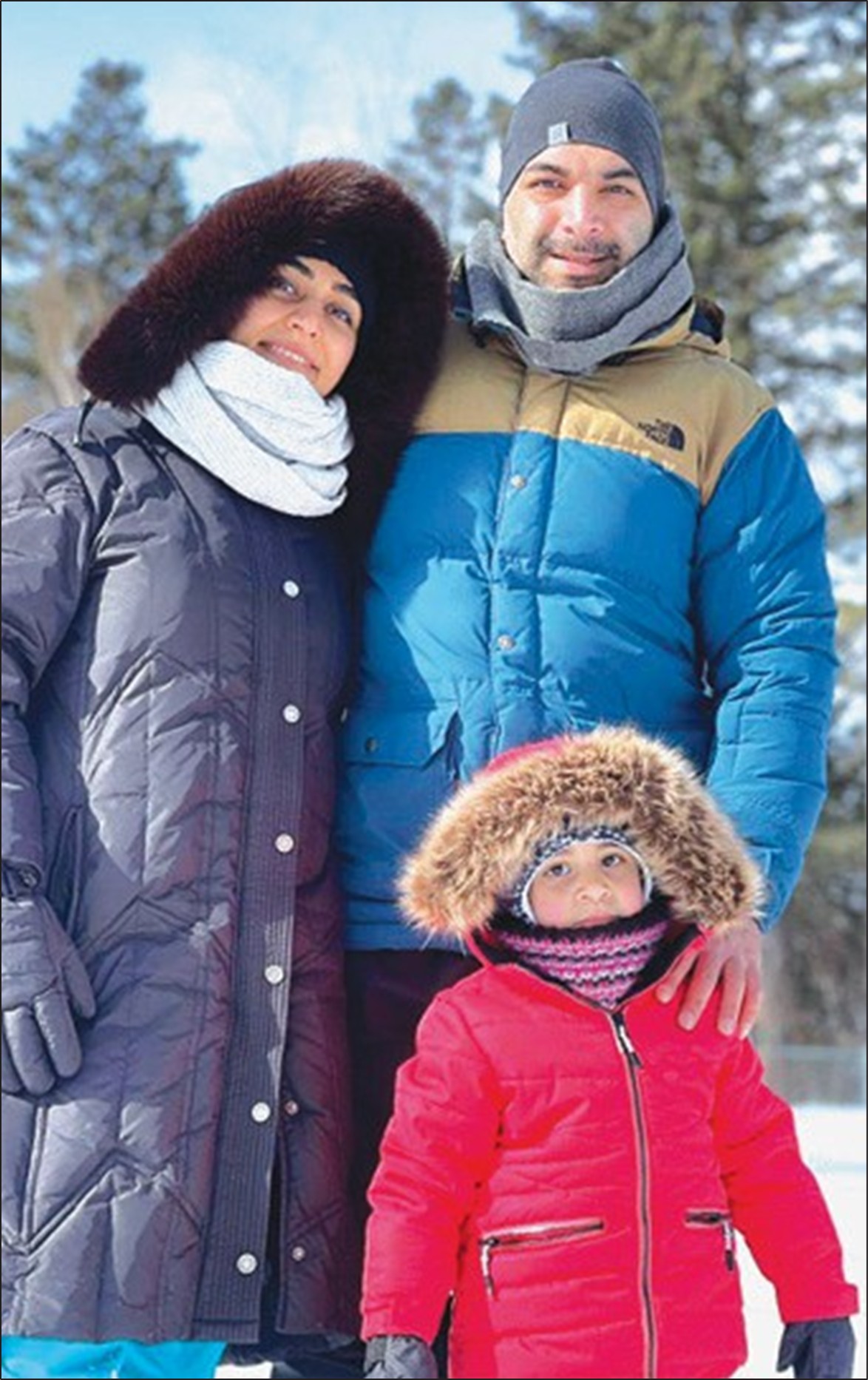

Malekpour was most at home on a hiking trail, according to his brother-in-law, Mohamad Eftekhari. “When I first met Saeed in Iran 12 years ago, he and Fatima [Mohamad’s sister, now Malekpour’s wife] and I would go hiking and biking together,” said Eftekhari. “He was full of energy, a real outdoor guy. I never heard him talk about politics.”

Eftekhari, now 27 and living in Toronto, was delighted at Saeed’s marriage to his older sister. Fatima Eftekhari came to Canada eight years ago so she could continue her studies. Fatima planned the couple’s future, and the move from Tehran to Canada — first to St. Cath-arines, where she attended Brock University, then to Vancouver Island. She would finish her PhD there, at the University of Victoria, and Malekpour would follow in her academic footsteps.

Malekpour’s mechanical engineering degree was from a Tehran university, but without Canadian experience his job search was stymied. That would change, he hoped, with a Canadian degree. In the meantime, his computer skills earned money for his school fees.

By the fall of 2008, she was enrolled in a post-doctoral program at the University of Toronto and preparing for their move east.

In October of that year, the malignant brain tumor suffered by Saeed’s father had progressed, leaving him only days to live, and Saeed made an urgent trip to Tehran. Within days, the authorities arrested him, plucking him off a Tehran street.

“At its heart,” says Hadi Ghaemi of the International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran, “Malekpour’s conviction is [an attempt] to stoke fear by suppressing user-generated content and Internet applications” that allowed Iranians to interact in cyberspace. The guards made it clear he would be an example to others.

“Failure to carry out swift punishment using all legal means would hurt crime prevention and increase the brazenness of [cyber] criminals,” said a statement issued after Malekpour’s death sentence was handed down. And it added that the Revolutionary Guard had plans to make other arrests on similar charges — a seeming warning to Iranians who use the Internet for political purposes.

The charges focused on his contract work as a web designer in Canada, and expanded to accuse him of running “the biggest anti-religion pornographic Farsi network.”

Protests of innocence were met with more beatings, kicks to the head, lashings with cables, according to a letter he later wrote from jail. His jaw was smashed and his teeth broken. Half his body was temporarily paralyzed. There were threats of rape and a slow death in a blazing furnace room.

Solitary confinement followed, in a coffin-like cell. At the end of his endurance, Saeed gave in. His videotaped “confession” was quickly circulated on Iranian media as absolute evidence of his guilt. The family says his ailing mother then had a heart attack.

When Saeed was arrested we didn’t know what to do,” brother-in-law Mohamad Eftekhari told the Star. “Fatima arrived in Iran, and I was still living there. We hadn’t a clue about why he was taken. He had no political involvement and he’d done nothing wrong. For three months, we went to the Judiciary, to attorneys. Everyone ignored us.… It was difficult to get a lawyer. They knew that if the Revolutionary Guard was involved, nothing could be done.”

Payam Akhavan, an international law professor at McGill University in Montreal and co-founder of the Iran Human Rights Documentation Center, says, “Iran has an injustice system. It has a series of vague laws relating to security, morality, waging war on God. They can be manipulated at will to prosecute, intimidate and eliminate dissidents.”

Malekpour is not alone. Canadian Hamid Ghassemi-Shall, a Toronto shoe salesman, is also on death row on espionage charges that are widely condemned as politically motivated. His family believes they relate to suspicions about his brother, a former Iranian naval officer who was arrested shortly before him, in 2008, and died in Evin.

Another Canadian, Hossain Derakhshan, known as Iran’s “blogfather” is serving close to 20 years in jail.

“Malekpour’s case is special,” says Maziar Bahari, author of “Then They Came For Me,” about his own time as a political prisoner in Evin.

“He’s among the first that the Revolutionary Guard’s cyber crimes department arrested. They even mentioned him several times [in the media], saying that they have the technological savvy to hack into websites and lure people back into Iran. He’s like a trophy for them.”

Malekpour had managed to send a letter from prison detailing what he described as torture, which left him with painful long-term injuries. The news reports that followed apparently infuriated the Revolutionary Guard.

“One very obvious sign of what he’d suffered was that they broke his teeth and jaw,” said Arman Rezakhani, who was held in the same cell with Malekpour but now lives in Texas. “It was also infected. He managed to keep up his spirits. But then they put him in solitary confinement after the letter came out.

“The worst for Saeed was the psychological torture, when they said [falsely], ‘We have your wife and we’re doing this to her’ or ‘we know where your sister is now.’ That wrecked him. When he came back to our ward, he was like a different person. He was in bad shape. He began to snap at everyone.”

“The food was not even recognizable as food,” said Rezakhani. “In the winter, the cell was very cold and they turned on the air conditioning so people would get sick. But only one prisoner a week was allowed to see a doctor. Once, when it was Saeed’s turn, he was very sick with fever and chills but he gave his appointment to me.”

With more than 30 men in a windowless cell two stories below ground, some slept on squalid cots, others on the filthy floor, covered by rough mats. There were three toilets for 150 prisoners. Exercise was an occasional walk in a dank courtyard so narrow that many prisoners preferred to stay inside.

Unlike Malekpour, Reza-khani had an end to his torment. He was released — leaving behind the man who had become his closest friend. “We just hugged and cried,” he told the Star, his voice breaking. “Saeed said, ‘Don’t make the same mistake I did by coming back to this country. Just get the hell out.’”

Mehrzad Boroujerdi of Syracuse University in New York State, said, “I think Malekpour’s case is very serious. After the assassinations [of nuclear scientists], they are getting more paranoid. Anything to do with computers, or the military, is a red flag.