September 01, 2017

An Iranian-American couple who got tripped up briefly by Donald Trump’s executive order have gotten fed up with Trump’s biases and are thinking of moving to Canada.

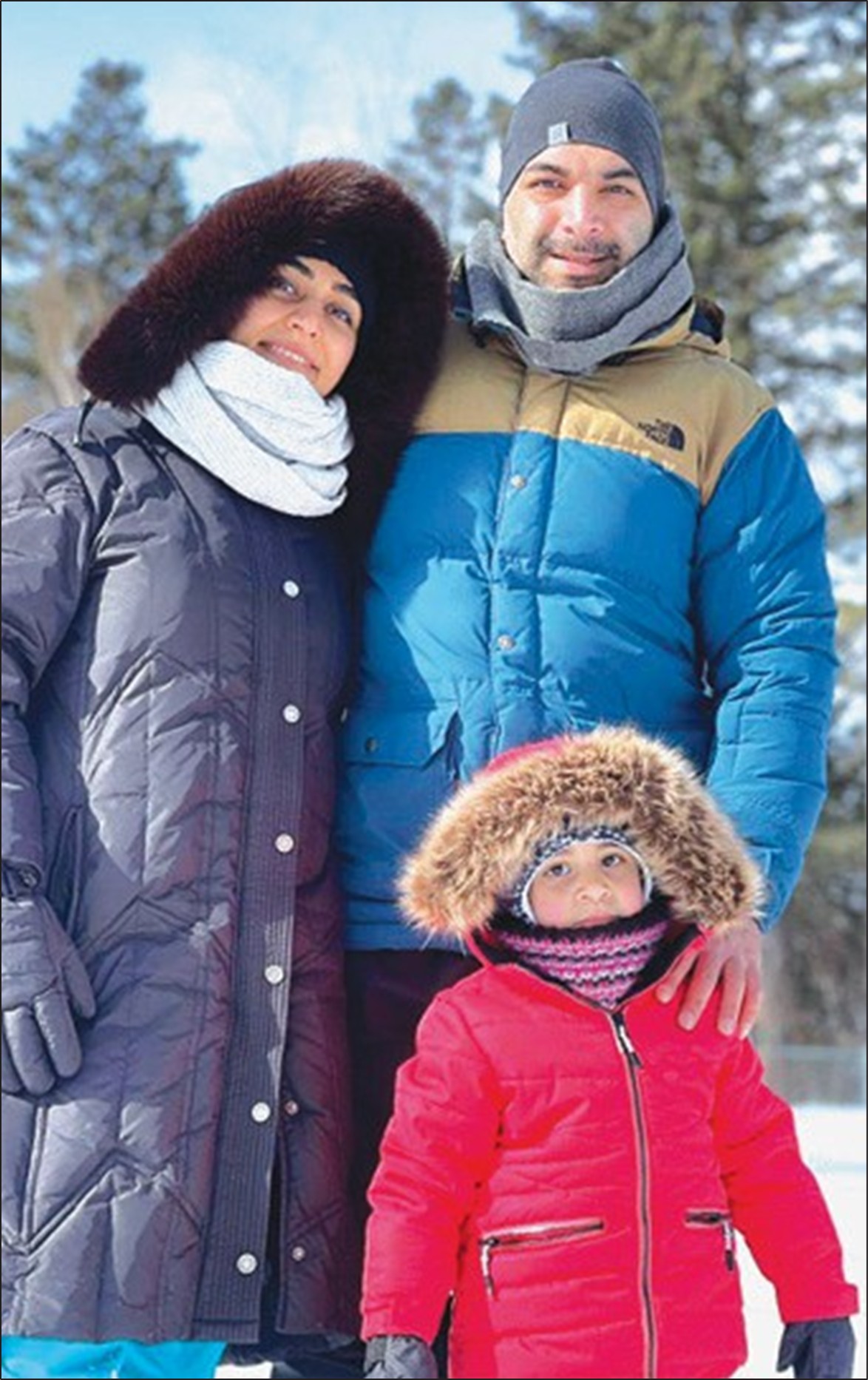

Seven months after winning their fight to be reunited in the United States, Aref Bolandnazar and his wife, Roya Arablood-ariche, are considering leaving their American home for good.

On Friday, January 27, Trump signed his order immediately barring entry to the US by citizens of Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria and Yemen for 90 days.

The following day, Arab-loodariche was refused boarding by Turkish Airlines at the Esfahan International Airport.

The married couple had made a last minute decision for Arabloodariche to stay an extra week in Iran to spend more time with her family. Bolandnazar, who is completing a PhD in finance and economics at Columbia University in New York, had returned to begin classes.

Arabloodariche traveled back and forth three times between Tehran and Esfahan, her home city, attempting to find a way back to her husband. She also tried to fly to Qatar after hearing a rumor Qatar Airways were allowing passengers to board.

On Friday, February 2, US Federal District Judge James Robart issued a restraining order immediately halting the travel ban, allowing travel to temporarily recommence.

Bolandnazar immediately bought his wife a ticket home. When she arrived at John F Kennedy International Airport in New York, the terminal was full of volunteers, lawyers and protesters. “It was like coming back from war,” Bolandnazar said. “Everyone was clapping.”

Bolandnazar said he originally chose to leave Iran because he “found many people were irrational — it may be racism, it may be fascism, it may be anything that could be resolved with a little thinking.”

Eight years ago, he was detained along with 23 other students after participating in the protests over the re-election of President Mahmud Ahmadi-nejad.

After he was released, Bolandnazar felt he had no choice but to leave Iran. “We had the idea we cannot stay here — I was suffering, not because of what they did to me, but because I couldn’t stand the corruption.”

Yet, despite the fight he and his wife have had to reunite in the US, Bolandnazar and Arablood-ariche have been left feeling disillusioned with their new home. They are considering leaving, possibly returning to Canada where they have lived before.

“To see people who cannot tolerate, who are not rational, who follow their fake news and rumors, who don’t hear, who don’t think,… I really did not expect to find those kinds of people in western countries,” Boland-nazar said.

Sina Nassiri, an Iranian citizen, lived in Philadelphia for six years while he was completing his PhD in biomedical engineering at Drexel University. He says there’s really little new with the Trump Administration. The vetting for Iranians was very strict even under Barack Obama. He says his family attempted to visit him in the US. His mother and sister were granted visas after three months. They traveled to the US without Nassiri’s father, who received his visa only five months later. “My parents said, ‘Son, we love you, but we cannot do this again’.”

Nassiri says Trump’s travel ban makes very little difference to the situation of Iranians. “The big difference was they [the Obama Administration] weren’t being vocal about it,” Nassiri said.

According to Adam Cox, a law professor at New York University, the US immigration system is informal, opaque and allows immigration officials tremendous authority. For people attempting to gain entry or remain in the US, navigating the system is difficult.

Professor Cox’s first case as an immigration lawyer was representing Olivier Garcia, a man he never met nor spoke to.

Garcia had been in immigration detention for several months and was facing deportation. Professor Cox filed papers with the court to enter an appearance as Garcia’s lawyer.

The next morning, Professor Cox received a call from Garcia’s sister. She had just received a call from an Immigration and Naturalization Service agent informing her Garcia had been deported to Tijuana, Mexico.

Professor Cox immediately began contacting INS officials to work out what had happened to his client. After “hours and hours of run around and weird obfuscation” he received another call from Garcia’s sister.

Garcia was back in US custody. To this day, Professor Cox doesn’t really know what happened with Garcia, but said it was an eye-opening experience into the US immigration system. “Holy cow, it’s like the Wild West,” he said

There have been repeated efforts to professionalize how immigration agencies operate, which Professor Cox called a “crazily informal process.”

For both Democrats and Republicans, the current informality of the immigration system is beneficial. Policy can be adapted to sudden crises.

“We have a system that permits the executive branch tremendous authority to change immigration policy quite quickly and to adopt pretty aggressive policies,” Professor Cox said. “What’s been extraordinary, really unprecedented, is the period leading up to it backed by openly racially charged rhetoric.”

After 9/11, the Bush administration implemented a policy called the National Security Entry-Exit Registration System (NSEERS), which required special registration requirements of the citizens of 18 Muslim majority countries (including Iran) plus North Korea.

The Immigration and Naturalization Act (INA), the body of law that governs US immigration policy, gives the US Attorney General and the Secretary of Homeland Security the power to require special registration procedures of essentially any non-citizen in the country except for green card holders.

Litigation was taken against NSEERS on the argument the policy was targeting individuals on the basis of race and religion. That litigation failed.

While American constitutional law makes it easy to attack laws that single out individuals because of their race or religion, it is difficult to prove the discriminatory intention of the law.

The travel ban has been successfully opposed because of Trump’s election talk, both on the campaign trail and Twitter, of implementing a Muslim ban, which explicitly linked the denial of entry to the US to an individual’s religion.

“It’s really unique because you’ve got all this public evidence you normally don’t have,” Professor Cox said.