December 23, 2016

Iran and Turkey are on a col lision course that could end in war, the International Crisis Group (ICC), a respected think-tank based in Brussels, warned last week.

The main problem is rival interests in Syria and Iraq that have the two countries supporting opposite sides.

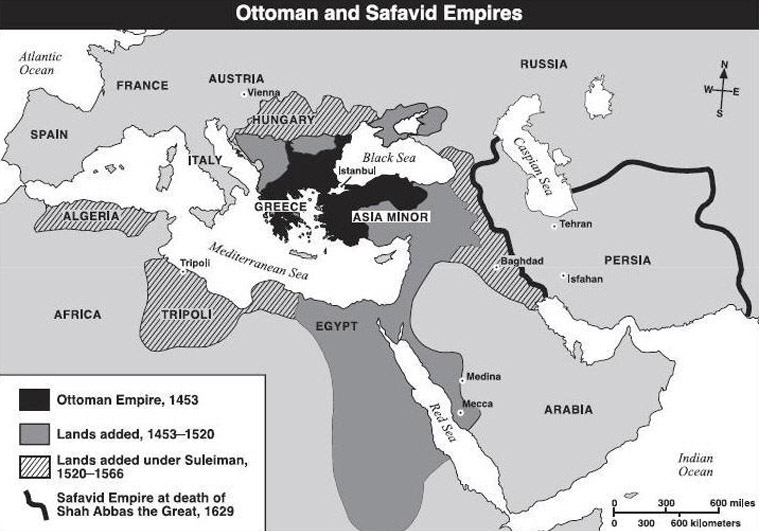

Iran has long played down frictions with Turkey, insisting that all has been peaceful for 500 years—a slight exaggeration as they actually fought a war almost two centuries ago.

But the ICC says, “Today, while their economies are increasingly intertwined, a profound disagreement over core interests in Iraq and Syria is putting these two former empires on a collision course.”

It says that since the Arab Spring erupted in 2011, Iran and Turkey have repeatedly bumped into one another “over what each sees as the other’s hostile maneuvering” in Iraq and Syria.

The ICC writes in a briefing paper: “Though both have attempted to build on shared interests – defeating or at least marginalizing Islamic State (IS) and curbing the rise of autonomy-minded Syrian Kurds–– deep suspicions about the other’s ambitions to benefit from the chaos have stopped them from reaching an arrangement that could lower the flames.

“The dynamics instead point toward deepening sectarian tensions, greater bloodshed, growing instability across the region and greater risks of direct“– even if inadvertent–– military confrontation between them where their spheres of influence collide. The possibility that an Iranian-made drone killed four Turkish soldiers in northern Syria on 24 November 2016, as Ankara alleges, points toward perilous escalation.”

Turkey and Iran have long competed for hegemony in their shared neighborhood. But since the last full-scale Ottoman-Persian war (1821-1823), they have maintained largely peaceful relations. However, the ICC argues, the Arab Spring “gave both countries, posing as champions of the popular movements, an opportunity to remake the region according to their own interests.”

The ICC describes the problem this way: “Turkey and Iran harbor deep mutual mistrust. Suspicions are evident even in the bilateral economic realm. They are particularly acute, however, regarding regional maneuvering: each views the other as seeking hegemony, if not to recapture lost glory, through violent proxies….

“Iran decries Turkey’s active support of the [Syrian] opposition in its attempt to bring down the Syrian regime, thus endangering Iran’s strategic link with Hezbollah in Lebanon, and accuses it of supporting Sunni jihadist groups in Syria and allowing IS recruits to transit its territory on their way to Syria and Iraq.

“Turkey is alarmed by what it sees as Iranian support for the PKK [the Kurdistan Workers Party that has long been fighting the Turkish government in Ankara] and its affiliates in carving out an autonomous zone on its border with Syria, and by the actions of these same groups and Iraqi Shiite militias in northern Iraq, once the Ottoman province of Mosul (Mosul Vilayet) and still viewed by Ankara as its ‘turf’. It deems these developments a direct threat to the stability of its borders with Syria and Iraq and the area’s Sunni inhabitants.”

The ICC says, “Tehran interprets Turkey’s Syria policy as primarily a product of a neo-Ottoman ambition to regain clout and empower pro-Turkey Sunnis in territories ruled by its progenitor. ‘What changed in Syria [after 2011] was neither the government’s nature nor Iran’s ties with it,’ an Iranian national security official said,’‘but Turkish ambitions.’ Moreover, Iran blames Ankara for not stemming the flow of Salafi jihadists through Turkish territory into Syria and for giving them logistical and financial support.”

There is something of a mirror image on the other side, the ICC says, with officials in Ankara arguing that “Iran seeks to resuscitate the Persian Empire – this time with a Shiite streak – and to do so in formerly Ottoman territories.”

The ICC notes that in March 2015, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan accused Iran of fighting IS in Iraq “only to take its place.”

The two countries tried dialogue. In between meetings with US Secretary of State John Kerry, Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad-Javad Zarif frequently traveled to Ankara or received Turkish diplomats in Tehran to try to iron out the disputes. But all efforts came to naught.

“With each failure to find an accommodation,” the ICC says, “the context of Turkey’s and Iran’s rivalry has become more complex and disagreements more intractable. What they have in common in Syria is that neither can tolerate a divided country or complete disorder. What is critically important for Iran, however, is that whatever order there is preserves Syria’s geostrategic orientation as part of the ‘axis of resistance:’ to project power into the Levant, generally, and to keep its strategic depth vis-a-vis Israel via its link with Hezbollah, in particular.

“While Turkey would like to see [Syrian President Bashar al-] Assad gone and a more inclusive Sunni-led order emerge in Damascus that would be friendlier, its absolute priority is to have a stable border and a curb on PKK-led Kurdish aspirations.

“Both seek to preserve Iraq’s territorial integrity as well, but ensuring Shiite-majority rule is as critical for Iran as a more inclusive role for Sunnis in governance is for Turkey.”

The most immediate source of tension, says the ICC, is that Turkey now sees Iran encroaching on its historic spheres of influence—namely Aleppo and Mosul.

“Iran-backed Shiite militias (al-Hashd al-Shaabi) have indicated intent to push toward Tel Afar, an old Ottoman garrison town west of Mosul with a majority Turkmen population, ostensibly to prevent IS fighters from escaping toward the Syrian border. The prospect of Shiite militias entering Tel Afar alarmed Ankara, which deployed tanks and artillery in Silopi close to its border with Iraq to warn of intervention in case of reprisals against the city’s Sunnis….

“The view in Tehran is the opposite: Turkey is seen as seeking to create a Sunni-dominated federal region in northern Iraq with greater autonomy, as suggested by some Iraqi Sunni politicians close to Ankara, ostensibly to protect minority communities, in reality to counterbalance Iran’s influence elsewhere in Iraq.”

The ICC says, “That each side perceives the other in a zero-sum light provides further impetus for proceeding on the current course. Each appears determined to spoil the other’s prospects. Ankara, a Turkish security official said, ‘fears Iran’s triumph in Syria or Iraq will embolden it to step further into our turf’.”