May 13, 2016

After almost four years of silence about “closing” the Strait of Hormuz, the Islamic Republic resumed its bluster last week, with Gen. Hossain Salami, deputy commander of the Pasdaran, saying Iran might block entry to the Persian Gulf by American and even Arab warships.

The threat has a long history. But Iranian officials largely stopped making the threat in the summer of 2012, when the harsh new sanctions took hold.

Last Wednesday, however, the threat was back. Salami said, “If the Americans and their regional allies want to pass through the Strait of Hormuz and threaten us, we will not allow any entry.”

That would be an act of war and isn’t a threat taken seriously in the West.

But Salami even threatened to bar entry to America’s “regional” allies, meaning the Arab states across the Persian Gulf, whose warships are already based inside the Persian Gulf.

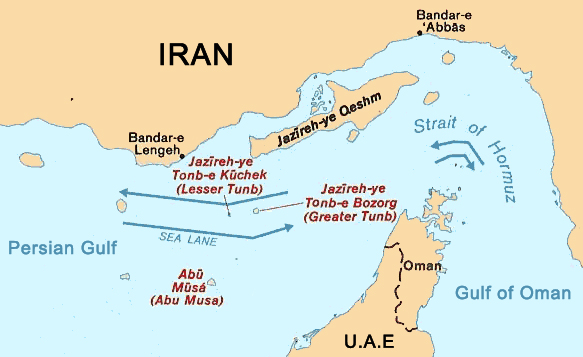

Salami said, “Based on the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, Iran will decisively confront any menacing passage through the Strait of Hormuz.” But the strait is an international waterway under that convention and a blockage by Iran would set off war sirens.

The legal details are not the key issue, however. The real issue was why Iran has chosen to renew its threats to close the strait. Such threats reached high decibel level in the first half of 2012 as the US and EU prepared to throttle Iran with the harshest sanctions yet. They took effect July 1 of that year. Immediately after that, Iran grew mum about the strait, suggesting the threats had been nothing but an effort to stop the sanctions. Now, three months after the removal of most sanctions, Iran has dusted off the old threats again.

Shortly before Salami spewed out his threat, the US Navy stopped escorting US- and British-flagged commercial vessels through the strait, something it had been doing the past few months since an Iranian warship carried out a missile-firing test in the waterway. Some thought Iran felt emboldened to re-new the threats after seeing the escorts end.

Former Iranian diplomat Mehrdad Khonsari told the Voice of America the closure threat was just rhetoric chiefly intended for domestic consumption. “The reality is that the Iranian Navy is incapable of blocking the Strait of Hormuz,” he said.

Naval analysts have generally said Iran cannot physically block the strait but can scare off shipping by saber rattling. Artillery on shore could quickly scare off ships. A few mines dropped in the strait would likely have the same effect—but water flows through the strait at such great speed that mines would be swept away. The strait is very deep so the threat of sinking vessels to block passage is a non-starter.

But talk about blocking the strait could drive up the price of oil. And some wonder if that might be why Salami chose to re-new the old threat now.

Back in 2012, the Hormuz rhetoric flew fast and furious from Tehran in the weeks before harsh sanctions took effect, with some officials saying Iran would close the strait if it was merely threatened by the West—which Iranian officials say the West does every day—or if oil exports were merely reduced—as they were on July 1, 2012, when EU member states halted all purchases of Iranian crude.

Then on July 7, Major General Hassan Firuzabadi, the senior officer in the Iranian military as chief of the Joint Staff of the armed forces, killed the high-blown rhetoric.

“We have plans to close the Strait of Hormuz,” he said, “because military commanders must have plans for any situation. But Iran, acting rationally, will not close the corridor through which 40 percent of the world’s energy passes, unless its interests are in serious trouble.”

That phraseology served to push the Hormuz threat aside. It was, of course, a very vague formulation, but the Islamic Republic much prefers vagueness to precision; that gives it more room to maneuver and also avoids offending any particular group within the establishment.

Firuzabadi’s main purpose appeared to be to lower the rhetorical heat, something Firuzabadi does not normally do. The fact that he spoke and did so in an unorthodox (for him) manner suggested he had been directed by the Supreme Leader to cool things.

Some of the hotheaded rhetoric had come from officers under Firuzabadi. The general acknowledged that. “What my colleagues say regarding [the strait] echoes missions assigned to them,” he said. “But the order to carry out the mission will only come from a decision by the Supreme National Security Council [chaired by the president] and approved by the Supreme Leader.”

Firuzabadi’s remarks were clearly intended to show Iran was “acting rationally”—his own words—and had a structured system of governance for making strategic decisions that are not left to hot-headed officers.

(There were also hotheaded legislators. A third of the members of the Majlis signed on to a draft bill that called for blocking tankers seeking to traverse the strait with Arab oil destined for countries that had stopped buying Iranian oil. That bill simply disappeared once the sanctions took hold.)

Analyst Keith Johnson, writing in Foreign Policy magazine last week, said Firuzabadi killed the hot rhetoric in 2012 after “a stern warning from China’s then-premier, Wen Jiabao.”