March 20, 2016

by Warren L. Nelson

Eighty years ago, an irate Reza Shah tried to get the United States to change its Constitution in order to stop American newspapers from labeling him a “former stable boy,” according to formerly classified US State Department documents.

The original copies of the documents were declassified a few years ago at the request of the Iran Times.

The documents reveal a Shah sensitive to criticism, an Iranian Foreign Ministry embarrassed to be raising the issue, and an American State Department at first anxious to try to placate the Shah, but then progressively more peeved at the Shah’s arrogance.

One reason the documents are interesting is that they paint a vastly different picture from the one portrayed by the Islamic Republic, which likes to show the Pahlavi regime—both Reza Shah, who reigned form 1925 to 1941, and his son, Mohammad Reza Shah, who reigned from 1941 to 1979—as patsies or tools of foreigners.

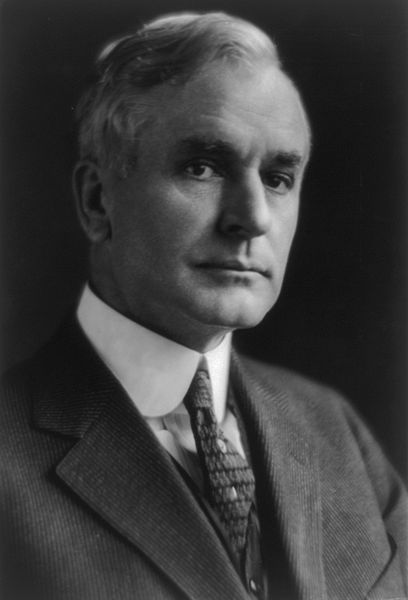

The documents, dating back to 1936, portray a Reza Shah who thought it was quite proper to tell the Americans how they should change their Constitution. Most of the US documents were signed by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Secretary of State, Cordell Hull.

The incident was set off by the publication February 8, 1936, in The New York Mirror, a long since defunct daily, of an article describing the Shah as “formerly employed in the stables of the British Legation in Teheran.”

This prompted a formal diplomatic message from Tehran to Washington threatening to break diplomatic relations and even sever trade if the Mirror were not disciplined.

The American charge d’affaires in Tehran visited the Foreign Ministry and tried to explain that freedom of the press was guaranteed by the US Constitution. Tehran said that if the Constitution permitted American newspapers to insult the Shah, then the American Constitution had better be changed!

Wallace Murray, the assistant secretary of state for Near Eastern affairs, wrote in a memo that he spoke with Iran’s charge d’affaires in Washington and pointed out “the unusual character of his government’s demands and emphasized again to him that the freedom of the press in this country is not merely an empty phrase but is a very actual reality. He said he realized this fully but that unfortunately the Shah of Iran did not and was unwilling to accept any such excuses where criticism of his person was concerned.”

The US State Department made efforts to mollify the Shah by contacting the Washington representative of William Randolph Hearst, the publishing magnate who owned The New York Mirror. Eventually, a retraction was published by the Mirror. But that did not satisfy Iran, which ordered its legation in Washington to close down and come home—although it allowed the American legation to remain in Tehran and thus did not break diplomatic relations.

Although American and Iranian diplomats hoped the matter would pass with time, time unfortunately brought another newspaper reference to the Shah as a former stable boy, this time in the Brooklyn Eagle on June 13, 1936.

This resulted in another painful meeting between the American charge d’affaires in Tehran and the Number Two man in the Iranian Foreign Ministry that underscored the extent of misconceptions held about the American system.

For example, when the American diplomat suggested it would be better if Iran sent a diplomat back to Washington so that he could try to prevent such stories, the deputy minister responded that Iran didn’t have enough money to go around bribing American editors or buying news stories. The American diplomat tried politely to explain that he did not mean the Iranians should pay for news, but rather butter up newsmen.

The Iranian Foreign Ministry also indicated it was concerned there was a plot afoot to put offensive articles into American newspapers. The Islamic Republic makes the very same allegation.

A sidelight to this brouhaha was found buried in the American archives with these documents. The Iran Times found newspaper clippings showing that when the Iranian charge d’affaires left Washington, he put up for auction a vast collection of carpets, silverware and art objects he had brought with him.

The US Customs Service looked askance at this because the Iranian diplomat had brought the items in as diplomatic effects and thus paid no import duties. A clipping from The Washington Star, yet another defunct daily, said the carpets put up for auction totaled an astounding 144,656 square feet—equal to 1,340 normal American room-sized rugs measuring 9 feet by 12 feet.

The article said the duty on those carpets alone would have been $72,323.25 in 1936—a sum that exceeds $1.2 million in 2016-value money.

The US Customs Bureau suspected the Iranian diplomat had brought in such huge quantities for profit rather than for use in the legation. In fact, it reported it found that only 26 of the items put up for auction had ever been used in the legation.

The file in the US archives does not indicate how the auction brouhaha was resolved. But we do know that relations between Iran and the Untied States were restored to a reasonably friendly basis and the First Amendment to the Constitution has not yet been altered to meet the Shah’s specifications.