US oil production in the week that ended March 6 hit 9.4 million barrels a day, the highest weekly average in the 156-year history of the American petroleum industry—and despite depressed prices.

That doesn’t look good for hopes in Iran that depressed prices will bring an end to production from the many high-cost wells in the United States.

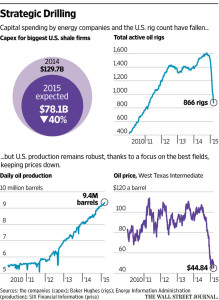

The number of oil rigs actively drilling in the US has been almost halved in the last half year. And the 2015 planned investments in exploration by US shale oil firms have been cut 40 percent from last year’s investments. But oil production continues growing inexorably almost every week.

The US weekly average output only passed 9.0 million barrels a day late in 2014, long after the bottom fell out of oil prices. But production is now up to 9.4 million and output is expected to continue to rise for months to come.

That doesn’t hold out the prospect of relief for the Islamic Republic, which has seen its oil exports fall by more than half under the stranglehold of sanctions. And it has seen its per barrel revenues plunge by almost half since the price collapse began last June. In other words, Iran’s oil revenues are now down to one-quarter what they were before the West tightened sanctions in 2012.

The Paris-based International Energy Agency (IEA) reinforced the prospect of a prolonged slump in energy prices Friday, saying US oil output was surprisingly strong in February and rapidly filling all available storage tanks. The Paris-based energy watchdog said this could lead to another sharp drop in crude prices in the coming months.

Last month, the IEA said a price recovery seemed inevitable because the US production boom was likely to cool. Instead, “US supply so far shows precious little sign of slowing down,” the agency said Friday. “Quite to the contrary, it continues to defy expectations.”

Independent shale-oil producers have slashed their planned 2015 spending on drilling by 40 percent from last year. But they have also promised to increase production by focusing on their best oil fields.

And The Wall Street Journal reported Saturday that many firms are adopting a new strategy that will allow them to pump even more crude as soon as oil prices begin to rise, which could prevent prices from rising much. They are drilling wells but holding off on hydraulic fracturing, or forcing in water and chemicals to free oil from shale formations. The delay in the start of fracking lets companies store oil in the ground in a way that enables them to tap it unusually quickly if they wish—and flood the market again.

This strategy could put a cap on how high oil prices can rise once they are recovering, said Ed Morse, global head of commodities research at Citigroup Inc.

“We’re in slightly unexplored territory,” Morse told the Journal. “It’s an experiment—a big, big experiment.”

The number of wells in Texas and North Dakota that have been drilled but aren’t yet pumping is at least 3,000, RBC Capital Markets estimates. That oil still in the ground “provides a war chest that could temper fundamental price spikes in the coming year,” RBC analyst Scott Hanold wrote Friday.

The number of oil rigs drilling in the US declined by 56 last week to 866, a 46 percent drop since early October, according to oilfield-service company Baker Hughes Inc.

Market observers have been waiting for US shale production to cool since November, when Saudi Arabia said it would keep pumping oil at the same volume to preserve its market share. Some members of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries said at the time that the move would force American producers to cut pumping because their oil is relatively expensive to produce.

But many firms had big debts they built up drilling expensive wells and continued pumping. To sell oil at $50 a barrel gave them more revenue with which to pay off debts than not sell oil at all and still face debt re-payments.