November 14-2014

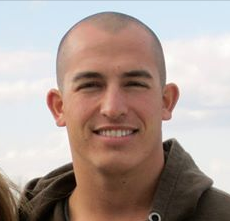

Nima Nassiri, 34, has been sentenced by a Michigan judge to spend 20 to 40 years behind bars for the beating death of his new wife, Sanaz Nezami, 27, last December.

Nassiri was born in Los Angeles. Nezami was from Iran. They met over Facebook and married in Turkey last August, then moved to the United States. They had been married less than four months when Nassiri beat his wife to death.

Nezami’s family in Iran agreed to the donation of her organs, which went to seven different people in the United States.

The couple had only just moved to the Upper Peninsula of Michigan so that Nezami could attend Michigan Technological University. They knew hardly anyone in the area, but hundreds showed up for her memorial ceremony.

In September, a Michigan jury convicted the husband of second-degree murder in the bludgeoning death after a three-day trial.

Nassiri, who stands less than five-feet tall, testified in his own defense, admitting that he repeatedly struck

Nezami, but arguing he didn’t intend to kill her.

On the night of December 8, she dialed 911 and was recorded saying, “Hi, it’s an emergency call because my husband got so crazy.” The jury, as part of their deliberations, asked to listen to the 911 tape.

In closing arguments, Houghton County Prosecutor Michael Makinen concentrated on what led to Nezami’s death.

“The cause of death was pounding her head on the floor,” Makinen said. “And he knew pounding her head on the floor like that could cause serious injury and that’s what’s necessary to convict him of second degree murder.”

Defense counsel David Gemignani implored the jury to decide if there was intent and he insisted there was no evidence of any intent to kill. “This isn’t premeditated,” Gemignani said. “This isn’t planned. It’s a horrible thing that happened when Nima’s in a rage and is not even realizing what he’s doing.”

After hearing both sides, the jury reached a guilty verdict on second-degree—non-premeditated—murder. Nassiri could have received life in prison under Michigan law.

Just one year before she died, Sanaz quoted a message that tried to answer the riddle of life and death in her Facebook page.

“The real question is not whether life exists after death. The real question is whether you are alive before death,” said Sanaz’s December 9, 2012, Facebook post, quoting a mystic from India.

When Sanaz was admitted to Michigan’s Marquette Hospital, no one knew anything about her. It was then that the medical team decided to search for any information they could find online. Seeing a phone number in an online resume for Sanaz, one of the members of the medical team dialed the number.

It was the family phone number in Iran. Sanaz’s sister, Sara Nezami, who speaks fluent English, answered the phone.

She said that after marrying August 2013, the couple flew to Los Angeles. In November, they drove across the country to Dollar Bay, Michigan, where they rented an apartment.

A hospital hookup with a laptop camera allowed the family to see Sanaz on her last days. She was declared brain dead three days after the beating.

After her death, the family authorized the hospital to transplant her organs, bringing life to seven others around the country, including a 12-year-old girl—people the Nezami family would like to be in contact with.

A Christian minister looked up Islamic burial prayers, which he read over the coffin as Sanaz was buried under the deep snows that enveloped the graveyard in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan.

Sanaz was considered a rare “ideal donor” and five surgical teams from four states converged on Marquette General where they recovered her heart, both lungs, liver, pancreas, kidneys and intestines for donation. Because of her small stature, some of her organs have gone to save the lives of children. It was Sanaz’s heart that was transplanted into a 12-year-old girl, The Mining Journal of Marquette, Michigan, reported.

“When she arrived here, her injuries were so extensive,… her brain was so damaged that she no longer had blood flow to her brain,” Gail Brandly, organ donation liaison at Marquette General, told The Mining Journal. “Unfortunately, that means that she’s brain dead and that’s irreversible.”

Brandly googled Sanaz Nezami and found her resume, which included the Tehran phone number.

Looking at her resume, Brandly said she saw that Sanaz was “well-educated, she’s into the environment, she’s into helping people.”

Sanaz’s credentials were also impressive. She had bachelor’s and master’s degrees in French translation. She said she spoke Farsi, French and English fluently and has “basic knowledge in Spanish, German, Arabic and a little Swahili.”

She also had a bachelor’s in environmental health engineering, which is what she planned to continue in Michigan Tech’s doctoral program.

“She was so studious, hard-working,” Sanaz’s older sister, Sara, told The Mining Journal by phone from Tehran. “You know when you saw her C.V., you can see that all her life she was studying. Of course, when she came to America, she wanted to be ‘the cream of the crop.’ She wanted to be the best.”

Sara also said Sanaz did a lot of charity work for the mentally challenged, the sick and the homeless. Though she was a Muslim, she also was part of a Christian congregation and believed that most of the differences between Christians and Muslims were superficial.

“She said, ‘God is the same—no difference between the people of the world,’” Sara said. “Maybe Christian people and Muslim people, there are no differences between them. People are the same, God is the same.”

After Sanaz passed away, Marquette General asked one of its resident physicians, a Muslim, to wash and shroud Sanaz’s body according to Islamic custom. Marquette’s Park Cemetery agreed to designate a section for Muslims so that Sanaz could be interred there. A $5,000 payment from the state crime victim fund paid for the burial, with the top of the casket pointing to Mecca and Islamic prayers recited in English.

The Reverend Leon Jarvis, an Episcopal minister and the hospital’s chaplain, read the prayers while about 20 people, mostly nurses and others who came to know Sanaz only in death, watched as the casket was lowered while snow fell December 18. Jarvis said, “I’ve never seen anyone so quickly adopted by so many.”

Sara said she thinks her sister would be happy to have helped so many people with the gift of transplants. “Some people spend money in charity for the other people,” she said. “But Sanaz gave life to those seven other people.”